Brian De Palma: Junk Art

A cinephile’s aesthetic or intellectual identity can be formed by his or her resistance to or alignment with De Palma’s sensibility.

A lap dissolve, joining Madeleine’s blood-soaked death mask with Bleichert’s tear-stained face resonates with unspoken guilt, a profoundly cutting emotional aftershock that Bleichert attempts, quite futilely, to fight.

Perhaps itself the victim of mutilation, The Black Dahlia never finds its own identity, the most unusual criticism I can conceive of for a De Palma film.

In truth, De Palma is neither a misogynist nor a feminist: women are often his camera’s subject and its object, and his films trade on the Hitchcockian fascination with the cinematic image of woman as a locus of desire and violence, attraction and disturbance

Where does De Palma stand? If he’s pandering, why is he so often unpopular? The ultimate badge of honor for a noteworthy American director: he has never won an Oscar, and he never will.

Graceful in its nearly clinical impersonality, Mission to Mars (2000) is De Palma-for-hire supreme: a CGI-dappled amusement flickering with faded traces of Spielbergian pathos but boasting a smooth, splendiferous surface and moving in an impressive array of ASC-amiable glides.

Considering that Brian De Palma’s oeuvre is so crammed with bravura set pieces and “Mind if I rewind that?” spectacle, the fact that Snake Eyes (1998) contains so many of his most thrilling moments alone qualifies it for something higher than the lower-tier lumping it generally receives.

He’d flirted with big action set pieces in Scarface and The Untouchables, but still, Mission: Impossible, with its globetrotting team of spies and extensive digital effects work was certainly a leap.

Everything about Carlito’s Way (1993) is improbable, starting with the fact that it’s a masterpiece.

Disreputable and trashy, Raising Cain was a “comeback” only in as much as it was merely another jab in the eye of those who found his earlier thriller concoctions needlessly intricate, labyrinthine, and softcore skuzzy.

Neither an aberration nor another bead on the necklace, The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) was the culmination of De Palma’s steady climb to the top of a Hollywood heap already dominated by his generational peers.

Time has only been kind to it, and now this most uniquely stylized of the 1980s American war movies is clearly worthy of a top-seeded spot in its category, as well as in its director’s vibrant oeuvre.

The Untouchables’ self-consciously recycled genre tropes never really ignite—that is, until the climactic staircase sequence, a nod to the Odessa steps slaughter in Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 Battleship Potemkin.

Wise Guys contains nothing to rate with the dizzying heights of which De Palma is capable—everything from Carrie through Blow Out has at least one or two fantastic bits—but it inspires a kind of affection that the rest of the director’s cold-blooded canon rarely manages.

The story goes that De Palma got extraordinarily sick of his buddies Spielberg and Lucas making the big bucks and tired of Coppola and Scorsese being exalted to the Olympus of cinematic auteurism, and that his response was a big “fuck you” to Hollywood in the shape of Body Double.

How did De Palma’s Scarface, a Hollywood extrapolation about minority machismo from 1983, become the apotheosis of gangsta symbolism?

His narrow gifts are so evident that it would be pointless to reiterate them. All his films require are the simple acknowledgement that the form he works in does not live and breathe with his particular exercises in it.

Like John Travolta's Jack Terry, I remain, long after Blow Out’s closing credits, haunted by a scream—so piercing, palpable, so full of anguish.

The greatest focal point of contention surrounding the film is just whose fantasy the film is; already from the steamy, softcore opening shot, which slowly peeks around the corner into an open-doored bathroom, De Palma has established multiple possibilities of point of view, which only become further confused and repeated and doubled.

Home Movies is definitely traceable as a piece of De Palma mischief, but at best it seems a sketch, and at worst unwatchably, smugly makeshift, something that even De Palma’s most woebegone gambits avoid.

The Fury is an urban reworking of Carrie’s notion of young adulthood as physical and psychological trauma.

I don’t think De Palma has ever been given enough credit for dragging the patriarchal dread of female sexuality into the light of popular culture.

Obsession nearly drips Hitchcock, so much so that while watching it I became preoccupied with the question of whether it’s even intelligible without the existence of Vertigo as an “intertext.”

Phantom of the Paradise manages to be angel and devil in equal portions—the binary opposition of De Palma picture and De Palma words finally brought together to create a harmonious whole.

It has some genuinely terrifying moments, it keeps a tight noose around the audience’s collective psyche, and, yes, if you’re looking for it, it takes several Hitchcock films and puts them in a blender. What’s rarely discussed is the comedy.

If you had to name some quality that allows the same man to make Dressed to Kill and Get to Know Your Rabbit, it would be his sense of a movie as an exquisite mechanism, all its parts (body and otherwise) whirring and shifting into place.

For those familiar with the concept of a De Palma film, this early-Seventies independent curio is at once a complete departure from his barely more “mature” work and a perfect example of the ambivalent countercultural origins that fed New Hollywood’s eventual “maturity.”

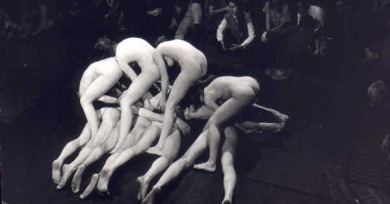

Dionysus (1970) is filmed on rough black-and-white stock, but its visual harmonies are elegant, sexy and surprising, exploratory yet rigorously controlled.

Given that Brian De Palma once openly proclaimed his desire to be the “American Godard,” there’s a certain irony to be gleaned from looking at how history has treated the earliest works of both filmmakers.