Jeff Reichert

Magellan is one of the few films to cover this episode of the Age of Discovery, and Lav Diaz uses this stab at a grand seafaring spectacular to reject the idea that white colonialists “discovered” anything at all.

For this new symposium, we asked our contributors to pitch an idea for an essay centered around a film that somehow utilized or enabled a technology (relatively new or more widely available at the time of its making) that was indivisible from the experience, meaning, or aesthetics of the film itself.

A Few Great Pumpkins

The Bad Seed, Halloween III: Season of the Witch, The Black Tower, Cure, Christine, What Lies Beneath, and When Evil Lurks.

Below the Clouds, though set in a relatively small area hunkered uneasily between the Phlegraean Fields to the West and towering Vesuvius to the East, is populated with incidents that invite the viewer to contemplate a broader, global apocalyptic moment.

Each story explores questions of indigeneity and its reaction or resistance to the imposition of Western law and order, but even though a character or prop might reappear across sections, and images occasionally rhyme, the chapters are distinct.

Everything in documentary filmmaking is an ethical question. Every placement of the camera. Every question you ask or don't ask is an ethical choice. But the hardest choices are made in the cutting room because that's when you really are saying, this will be seen by the world.

In Our Day sets two unconnected, rhyming narratives against each other for scrutiny—like looking at two paint samples from the same spectrum side by side and parsing the differences.

We asked our contributors to select a film they have written about in some form in the past. It could have been a review, a term paper, a passionate email, or a Post-it note. The writer may disagree with what they wrote, or they may stand by it. Nevertheless, they are now a different person, and we wanted to know about their personal journey with this particular film.

Bronx-born, Pittsburgh-forged George A. Romero is the possessor of one of the odder filmographies in American movies, and Knightriders, which trades undead hordes and jump scares for gallant knights and plainspoken earnestness, is an outlier.

Cinematically it is neither here nor there, sandwiched between agreed-upon renaissances. There were marvels, there were duds, there were mediocrities, like any year... Yet we discovered 1981 feels as much like a turning point as it does a middling cinematic interzone.

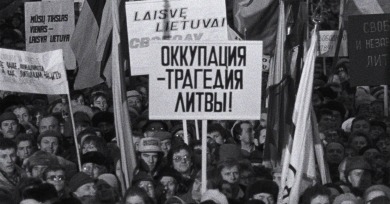

Over the course of four hours, Loznitsa constructs a granular record of Lithuania’s moves towards independence.

A pleasing sense of ambient drift marked a number of the landscape-focused True/False features I saw, a welcome respite from the “story” and character-obsessed rigidity that hobbles the American commercial documentary industry.

A simple prop cup, chosen by someone on the creative team for use in a commercial film production, communicates a highly specific vision of Christ and Christianity entire to its audience: modest and humble, unostentatious and definitely working class.

What does giving such primacy to the nonhuman and inanimate mean for the other elements onscreen, specifically the human or the animal? What does an object convey? What is its meaning within an art form that is itself so given to fears of impermanence?

A Few Great Pumpkins

Ghost Story of Yotsuya, Lord Shango, Malignant, Dracula, Carnival of Souls, Silent Night Deadly Night 3, When a Stranger Calls

As we write and rewrite the ongoing history of cinema, missing the great films and often paying far too much attention to the undeserving, and always, always uncovering more and more work worth writing and thinking about, we should remember: question the rubrics and heuristics, the received and accepted wisdom.

A new Reverse Shot short film creatively documents the private Critical Interventions symposium hosted at Museum on the Moving Image just before the pandemic closed down the world.

Maybe rigorous analysis needs always to be leavened with a certain degree of humility. This seems particularly important when we look at films from unfamiliar places and wish to address ideas of culture and place.

“Will haunt you after it’s over . . . makes us think about the role that food plays in our lives—both as social beings and creatures of the earth.” –Vox

A Few Great Pumpkins

Pulse, Host, Brain Damage, Let's Scare Jessica to Death, The Velvet Vampire, Deathdream, The Devil and Daniel Webster