Take Seven: Object Lessons

Introduction

In his 1960 essay "The Establishment of Physical Existence," Sigfried Kracauer wrote that "in using its freedom to bring the inanimate to the fore and make it a carrier of action, film only protests its peculiar requirement to explore all of physical existence, human or nonhuman." Since 2006, we have been featuring recurring symposiums at Reverse Shot—"Takes" as we call them—in which we ask writers to look at one constituent part of a film and then expand upon it in an essay. The most recent was an inquiry into cinematic time, asking writers to focus on one particular passage of duration in a film, whether long or short (subjective terms anyway). Other instances have been about a single shot, a single cut, a single instance of sound, a single use of color, and the shape of the screen frame itself.

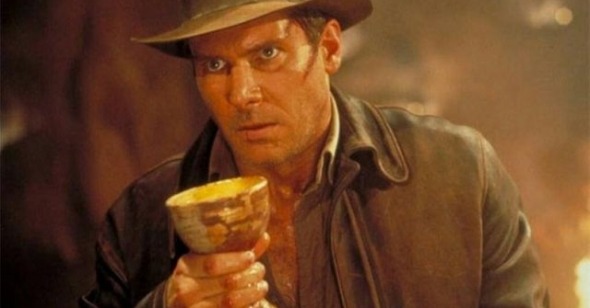

Now we have asked writers to focus on a particular object in a film. It could be literal or symbolic within the frame of the narrative; it could be incidental or central. It might have been created for the production or it might be a found object. It could be as obvious as a Maltese falcon statuette or as backgrounded as Jeanne Dielman's kettle. It just has to have meaning for the writer, and instigate an essay that speaks to larger ideas around the film in question. The only rule we imposed is that the object should not be ephemeral—like, say, food—and that it might, perhaps, still exist somewhere in our world.

As the publication of Museum of the Moving Image, which owns a vast and ever-growing collection of physical objects—only a fraction of which are on display—we feel that Reverse Shot has a special relationship to this idea, and we believe this was a fruitful project, touching on both the concrete, tactile elements of cinema and the ethereal, harder-to-define theoretical aspects of the form. Per Kracauer, what does giving such primacy to the nonhuman and inanimate mean for the other elements onscreen, specifically the human or the animal? What does an object convey? What is its meaning within an art form that is itself so given to fears of impermanence?

After just these few prompts, we asked our writers to go where they wanted with the assignment, and the result has been, as always, wide-ranging but hopefully, this time, quite tangible. Statues and tape recorders, bridal veils and brass balls: these are the objects that have stuck in our minds for reasons personal, political, or aesthetic.