Take Seven: Object Lessons

Literally attaching a prop to a character’s hand implies a directorial desire to micromanage the appearance and movement of his actors, yet Paltrow in The Royal Tenenbaums offers a rich example of how Anderson’s control-freak aesthetic paradoxically works best when inhabited by strong, idiosyncratic performers.

Le Samouraï presents us not for the first time with a fully interiorized, “locked-in” Melville protagonist, but one whose loneliness and single-mindedness are mechanized and supercharged. This object explicitly demonstrates his corresponding ability to unlock, infiltrate, and destroy the lives of others.

Legally Blonde teaches women not to derive power through the social mobility of marrying an old-moneyed white man. It teaches them to be self-sufficient as long as their conventional, “fun” femininity remains untouched by the realm of a more serious radical feminism.

Cover Girl, by Brooklyn-based artist Sara Cwynar, is a shimmering assemblage of images and items, images of items, objects, colors, and shapes, accompanied by a loquacious yet lethargic voiceover that intones indolently on and on until it becomes something like white noise.

A simple prop cup, chosen by someone on the creative team for use in a commercial film production, communicates a highly specific vision of Christ and Christianity entire to its audience: modest and humble, unostentatious and definitely working class.

Only through objects, through invitation, through some sort of channel, can evil gain access. And rather than reduce an audience’s capacity for fear, dolls exaggerate it. They’ve become a cinematic shorthand for the uncanny.

The carpets, which often line the floors and walls of the sets, both framing and filling Parajanov’s consistently delightful tableaus, present a vision of the poet’s world as something thought up by human imagination and crafted by human hands.

Valerie’s brass banana is an attempt to accumulate objects she hopes will add something, a bit of her own personality, to her tacky abode. Instead, its shiny surface only reflects her image back at her, an endless loop of bourgeois emptiness.

Frédéric senses that a vase highly sought after by one of the world’s leading museums would carry the same value—albeit sentimental—for Éloïse. But he is wrong. He mistakes his own values for others’ and for market values.

Nothing is random in Poetry, and it seems meaningful that the Renoir painting is a poster—a sign of humility. A poster is only a copy, a stand-in. It is and yet it isn’t Art—very much like Mi-ja’s burgeoning poetic sensibility.

Stasis, represented through this motionless object, allows us to make sense of the contradictions and the inevitability of change in this family. Where Noriko’s world is increasingly riddled with cracks, the vase is sturdy and whole; where her future is in a motion she cannot control, the vase is comfortably still.

Most memorable and haunting in my mind is the ceiling fan that hangs above the main staircase of the Palmer house. This deceptively ordinary fixture conjures true evil and subtly describes the tortured physics at work within the world of Twin Peaks.

Altman’s point is clear: we are constantly subject to casual injustices and banal evil. People in power can be fucked with, but they are rarely ousted.

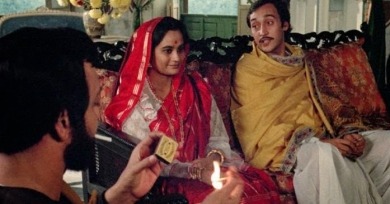

The Home and the World is focused on the efforts of two men with very different ideas about resisting colonialism and religious bigotry, but by opening the film with the town of Sukhsayar already in flames, Ray tells us in advance that their efforts are all in vain.

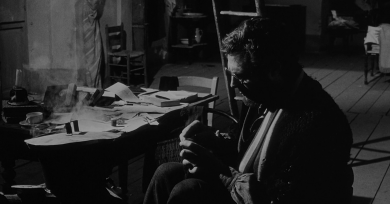

Among Mario Monicelli’s greatest gifts as a director was the expressiveness, specificity, and stubborn physicality of the worlds he creates. This textured, tactile realism is potent in The Organizer (1963), his epic tragicomedy about the nascent labor movement in late 19th-century Turin.

Paul Verhoeven’s psychosexual hall of mirrors remains worthy of a steel-plated prize for the best use of a kitchen utensil in a motion picture . . . Basic Instinct finds both men and women culpable in a time-honored mating game that has no clear rules barring the foolhardy pursuit of pleasure.

The narrative remains a storytelling marvel in the way it centers an object to both push the action along and toggle between characters while sneakily establishing the greater themes of unstable justice-lust and moral rot.

The film is breezy and carefree in a manner not often seen in narratives centered around women’s power. Not only does Marie never fail, there is never the sense that she even might.

It’s never confirmed that the film’s “right” Chinaman is a statue whose head stands still and straight. Yet this remains all a matter of perception, as well as interpretation. The object is thus tactile yet vaguely defined, and leads to a larger question: if the Chinaman doesn’t belong here, then what, or who, does?

What does giving such primacy to the nonhuman and inanimate mean for the other elements onscreen, specifically the human or the animal? What does an object convey? What is its meaning within an art form that is itself so given to fears of impermanence?

The baseline conceit of the actor as a ruthless authority figure derives from Blake and those brass balls, and how they wordlessly externalize the tumescent cockiness of their owner.

The zenith of this performance by Eartha Kitt, in which she dispenses with her own figurative veil, comes in an especially tragic sequence with a literal bridal veil, emblem of the refuge that has cruelly been denied her.