Bedatri D. Choudhury

All we see, throughout the 72 minutes of A Frown Gone Mad, are bloody faces and the back of Bouba’s arm administering the shots. But the specter of war and death in the Lebanese capital hovers like a shroud.

In both On Becoming a Guinea Fowl and I Am Not a Witch, the previous film by Rungano Nyoni, women are tasked with laboring and bringing normalcy to an off-kilter world, choosing to seek out other planes of existence to forge kinships and form communities.

In Dahomey, where its namesake country no longer exists in its original form and a community pretty much means all of a new nation’s citizens, the question of who receives the artifacts becomes contentious.

Sure, I make films as an artistic pursuit as an artist, but I make films to help my characters, my friends first.

A terrible event occurs, which would send most families into spontaneous combustion, but in true Fukada fashion, everything quietly implodes, and everyone is left to grapple with things in messy, dirty ways that feel truer to how our hearts and brains function.

The film dissects the status of Bangladesh as a postcolonial nation that, like many other postcolonial nations, tries to establish itself as a free nation while holding onto symbols that tie it back to the period it wants to (impossibly) outgrow.

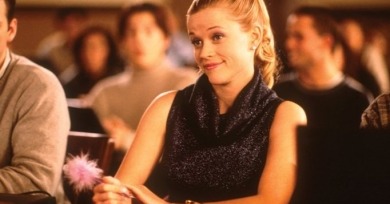

Legally Blonde teaches women not to derive power through the social mobility of marrying an old-moneyed white man. It teaches them to be self-sufficient as long as their conventional, “fun” femininity remains untouched by the realm of a more serious radical feminism.

Through decades of a certain kind of documentary storytelling and news reporting, audiences are so used to seeing images of poverty and abjection that the even the smallest act of affection comes across as extraordinary and radical.

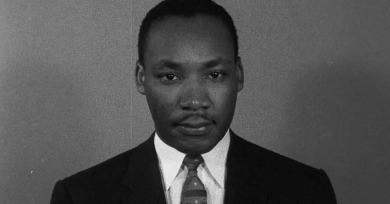

If one anticipates the declassification of the FBI reports on MLK, are we then complicit in the invasion of his privacy and the attempt to racially stereotype him? This film insists that what the FBI did to King is emblematic of what this country does when it fears those who might undermine its entrenched hierarchies.

A documentary about the 9to5 women's movement and an unsung Linklater drama paint an urgent portrait.

“Documentary, through its earliest forms, is a colonial concept. The white man appears and then because he is the master, he unveils the story the way he sees it. He literally becomes the seer,” says filmmaker Marjan Safinia.

Coded Bias, Time, and A Thousand Cuts are films made by women of color about women of color who have had enough with the status quo and taken it upon themselves to demand justice on their own terms.

In Téchiné’s film, she rarely indulges in grand gestures—looking at her notes, playing a violin, answering a doorbell. Her face doesn't betray much, but we see the turbulent waves, the currents beneath.

The oeuvre of Sabiha Sumar is essentially a feminist one, and more importantly, a Muslim feminist one. It is with this perspective that she questions, searches, and resolves.

This portrayal of an ugly divorce functions as a commentary on the dysfunctional post-Soviet, post-Communist Russia, where nothing holds value other than money and the desire to earn more of it.