On the Wire

By Bedatri D. Choudhury

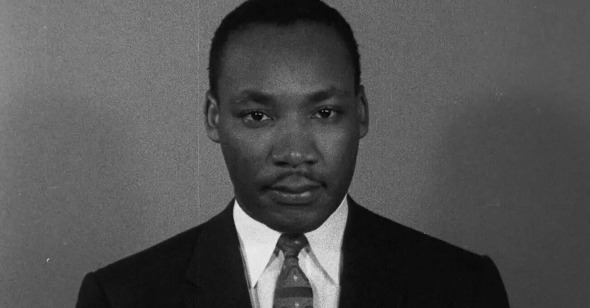

MLK/FBI

Dir. Sam Pollard, U.S., IFC Films

The portrayal of a Black man as a sexually threatening, bestial creature, out to prey on unsuspecting white women, is a racist cultural trope that has been in use for centuries. It has, through history, been the easiest fallback for anyone looking to discredit a Black man, most notoriously appearing in D.W. Griffith’s 1915 anti-Black propaganda The Birth of a Nation. And in his new documentary, MLK/FBI, Sam Pollard documents how the FBI exploited such stereotypes and hounded Martin Luther King Jr. because its director, J. Edgar Hoover, whose career spanned for 48 years, feared the “rise of a Black messiah.” The FBI, like other law enforcement bodies under the government, viewed Blackness as a threat to white supremacy and would leave no stone unturned to keep it from gaining popular support.

MLK/FBI, through extensive archival research, documents how the FBI, hoping to uncover King’s communist ties, wiretapped the phones of his associates. The FBI believed that Black Americans, especially King, with his close ties to suspected communist Stanley Levison, were particularly susceptible to ideas they considered subversive to entrenched hierarchies of race and gender in American society. Hoover’s paranoia equated anything related to the civil rights movement with communism, even if King was never connected to it (nor was Levison, for that matter). King and his rising popularity so disturbed Hoover that he had the FBI comb through King’s personal and public life to find something with which he could malign him. The opportunity presented itself when, by chance, a tapping of his associate Clarence Jones’s telephone revealed King’s extramarital affairs.

As seen in Pollard’s film, words like “beast,” “psychotic,” and “animal” make multiple appearances in the FBI reports that followed the wiretaps. Shortly before King received his Nobel Peace Prize, the FBI mailed a tape of King’s conversations with women to his wife, Coretta Scott King, accompanied by a letter written by an FBI officer pretending to be a Black civil rights activist disgusted with King’s sexual “deviances.” The letter gave King a deadline of 34 days, claiming “there is only one way out for you”—asking King to either kill himself or stop his activism. Around the same time, Hoover called King the “world’s most notorious liar.”

Martin Luther King Jr. posed an antithesis to traditional American masculinity, epitomized in the G-men of the FBI: white, secretive, athletic, suited men with briefcases working to quell disruptions and maintain the status quo. Dr. King, wanting to “absorb all their hatred in love,” embodied for them a dangerous upheaval of American society, revealing the stone-cold G-man as a stunted and outdated myth. Presenting King as a sexual threat, especially at a time when the civil rights movement was gaining momentum, was the easiest way to engineer a moral resistance to a Black man’s political ambitions.

To perpetuate white superiority and the unquestioned morality of the American state, the FBI found a ready mouthpiece in Hollywood. Pollard’s documentary includes numerous clips from films like The FBI Story (1959), Walk a Crooked Mile (1948), Big Jim McLain (1952), and Communist for the FBI (1951), illustrating the insidious normalization of surveillance in popular culture. MLK/FBI also explains the ways in which newspapers have played a part in making Americans believe that Hoover’s snooping, his invasion of the privacy of human beings, was the right thing to do. They disseminated misinformation, distributed doctored images of Dr. King attending “communist school” so widely that people readily accepted the State’s use of resources to quell dissent. Authorized by Robert and John F. Kennedy, aided by Hollywood and the Press’s misinformation, the FBI’s consistent campaign against Black people, and other dissenters and activists stooped so low that it didn’t hesitate from exploiting King's personal life. “This entire episode represents the darkest part of the bureau’s history,” says former F.B.I. director James Comey in the film.

In MLK/FBI we hear voiceover throughout, but we don’t see any talking headsuntil the credits roll. When we are not given the opportunity to witness the faces of the storytellers, we are forced to listen without our implicit biases kicking in. We are also compelled to make our own moral decisions without the luxury of falling back on the wisdom of a narrator. Pollard doesn’t incorporate images from our recent past to draw obvious parallels to now, but echoes to the times we are living through will not be not lost on the audience. The irrational fear of communists has returned in the mindless categorizing of every dissenter as “antifa.” Propaganda spread by newspapers, social media, cable TV news, Internet advertising, and people’s refusal to believe in historical facts, are very much a part of our realities. Additionally we’re living in a time in which State-ordained surveillance has been legitimized and normalized, with or without Mark Zuckerberg’s help. Pollard’s documentary reminds us that Hoover’s illegal COINTELPRO is not over—it has only changed name and form.

One of MLK/FBI’s greatest strengths is that it refuses to sensationalize King’s relationships. Pollard makes no effort to investigate whether the FBI’s claims are true or not. Instead, it meditates upon the assumptions that continue to drive the conversation around King. In the end, the guest speakers we see for the first time—historian Beverly Gage, civil rights leaders Andrew Young and Clarence Jones, and Comey—discuss the possibilities that may emerge after the FBI reports on King are declassified in 2027. At that time, the reports will become an empty signifier: how society reacts to them will be more important than their content.

If one anticipates the reports’ declassification, are we then complicit in the invasion of King’s privacy and the attempts to racially stereotype him? Pollard’s film insists that what the FBI did to King is emblematic of what this country does when it fears those who might undermine its entrenched hierarchies. No matter the contents of the files, an engagement with them will bring forth a reckoning with the violence that lies under America’s past and present. MLK/FBI doesn’t leave the audience with answers but compels them to ask harder questions. Pollard foretells the dirtiness of the politics that will surround the files’ declassification and warns us, in advance, to not get caught up in the text of the files, but rather to question their intent.