Reviews

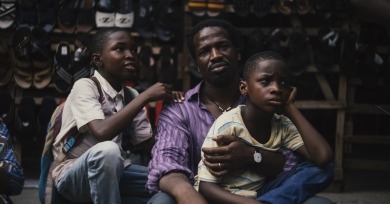

The filmmakers maintain that the character is not a direct representation of the father they barely knew but a broader symbol of paternal strength and the fallible masculinity it obscures. The resulting work is much less a memory piece than a sustained act of mournful imagining,

It is impossible to ignore that the decline of traditional print journalism has resulted in an eradication, and deterioration in quality, of the sort of work at which Hersh excelled. When Hersh cracks a self-deprecating joke about how he’s “slumming it” on Substack now, it’s hard not to despair.

It is outwardly dispiriting and disarmingly sweet, narratively brutal and formally subdued, thematically outré and structurally prosaic. It articulates taboo subjects with the matter-of-factness of the everyday, equally in tune with the absurdity and mundanity of the relationship it portrays.

The point here is not the destination or the shellshocked wanderers, but the conflagrations of sounds and visuals Laxe conjures along the way.

The most compelling throughline is that maybe it was absurd for brat to skyrocket in the first place, particularly in an entertainment ecosystem that requires its celebrities to be as mass market, palatable, likeable, and as ready and willing to sell out (without selling out) as possible.

Outside the context of the film, the piano score might sound like the accompaniment for a toasty night by the fireside. Yet Hunt’s minor chords and capricious melodies allow the film a gracious domesticity that works in contrast to its swollen, poignant portrait of disintegration.

Years in Review

Reverse Shot's annual awards and accolades, including Most Wasted Potential, Most Pointed Punchline, Best Experimental Biographical Documentary, Best Film-Within-a-Film, Best Supporting Actress and Actor, Most Acronyms, Most Sentimental Value, and more.

Its harmonious interplay of absurdist humor, eroticism, and politics are anchored by its deeply resonant human drama centered on memory and yearning.

Sound of Falling anchors the undulations of history in a physical structure, a home inhabited by generations of people. That allows Schilinski to enter the past through oblique, almost surreptitious, methods, which casts history as a moving amalgamation of life’s minor and mirroring moments instead of dramatic apexes.

Magellan is one of the few films to cover this episode of the Age of Discovery, and Lav Diaz uses this stab at a grand seafaring spectacular to reject the idea that white colonialists “discovered” anything at all.

Like late Ozu, with his parade of seasonally titled shomin-geki exploring the practically endless permutations of family life, Father Mother Sister Brother is a series of intergenerational vignettes.

Between its compositional dynamism and picaresque sensibility, the film is an auteur work to the core; it is also enervating in ways that do not so much undermine the stylistic pyrotechnics as indicate they’re the source of the problem.

Marty Supreme aims for something like grunge Barry Lyndon, a period picaresque epic about a sociopathic climber, but scrappy instead of stately, obnoxious instead of ironic. Yet beneath the grime it’s comparably handsome.