Mark Asch

Like late Ozu, with his parade of seasonally titled shomin-geki exploring the practically endless permutations of family life, Father Mother Sister Brother is a series of intergenerational vignettes.

Marty Supreme aims for something like grunge Barry Lyndon, a period picaresque epic about a sociopathic climber, but scrappy instead of stately, obnoxious instead of ironic. Yet beneath the grime it’s comparably handsome.

Diciannove, the first film by Giovanni Tortorici, who is not yet out his twenties, speaks to the psychic undercurrents of our fresh Hell, while also carrying on a dialogue with the traditions of European romanticism in literature and film.

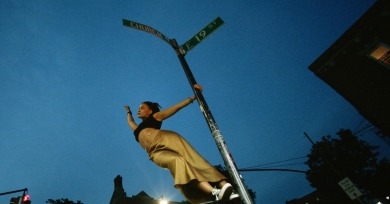

Blue Sun Palace represents a new aesthetic vernacular for stories of the New York City working class, betraying international inspiration more than Sundance-school neorealism.

The film is another of brothers Bill and Turner Ross’s immersions in the regional euphoric...The filmmakers are after a kind of Herzogian ecstatic truth, often to be found in the kinds of spaces where someone is likely to be rolling on literal ecstasy.

New York is always being built and rebuilt on its own ruins, and this palimpsestic vision of the city is inextricable from the consequences of gentrification—the city is always ejecting people like Dakota from its slipstream.

During the first days of the 2020 lockdown, when New Yorkers saw time opening out abyssally before them and for filmmakers any kind of large-scale production was impossible, Artemis Shaw found her old camcorder in her parents’ apartment.

Made at the height-to-date of the New York crisis of violence, it responds with a story steeped in simplistic moralism and frank bloodlust. It is black and white and red all over, like the front page of the New York Post, that eternal foot soldier in the culture war.

The film, starring Adele Exarchopoulos as a hard-living, pain-numbing flight attendant on a fictional low-cost carrier, is a welcome indictment of the leisure culture and spiritual malaise of the Common Market.

It was a film for peers of mine whose burgeoning selfhoods hinged on things more consequential than cinephilia. But watching the film now, I am newly surprised by how grounded I feel in the everyday world it transcends.

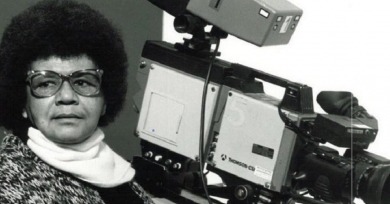

For this week's pair of writers, coping mechanisms including digging into the oeuvres of auteurs, from chronicler of the lonely American male Michael Mann to trailblazing Guadeloupean female filmmaker and activist Sarah Maldoror.

Juliette Binoche is one of the icons of the Miramax era, and this facet of her persona is one that radiates, if you will, through her filmography, casting the whole of it in a light that reads to many Anglophone viewers, especially, as symbolic of sensuality and sophistication.

The distance between the banality of life and the sublime of cinema seems practically unbridgeable. This sense that transcendence is elusive to us mere mortals is the explicit subject of the film.

The Executive Order that claims to Protect the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States inspires a writer to dig into his family’s Jewish American immigrant legacy.

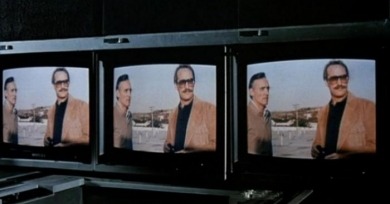

So, with this piece, I want to look at what, exactly, we saw, and what I think that means. I’ll do that by revisiting a film whose pan-and-scan presentation struck me, at the time I rented it, in the dying days of VHS, as a pinnacle of the pan-and-scan format: Michael Winterbottom’s 2000 drama The Claim.

Many of the qualities we associate with promising student filmmakers—voraciousness, audacity, experimental flair—are qualities we continue to associate with the septuagenarian director of The Wolf of Wall Street.

In thinking about a film from the last ten years that gives me hope for the next, I wanted to find some kind of reassurance that, even if most films will soon cease to exist as any kind of physical object altogether, they might still appear, to the future viewer, as dated as any saturated and seamy 35mm print.

With its catchy Cold War milieu, surveillance-culture sheen, and precariously hairpin plot, the film is more obviously topical than peak-period Peckinpah; the film’s sensationalism is a matter of its super-contemporary hook, rather than the more eternal, atavistic violence that was Peckinpah’s great subject.

Family members, especially in the city, live on top of each other. One major practical consequence of this is that, if you’re just learning how to masturbate, you’re not doing so nearly as privately as you think.