Closed Circuit

Mark Asch on The Osterman Weekend

Sam Peckinpah hadn’t made a film in five years when he was hired to direct 1983’s The Osterman Weekend; and he’d be dead of a heart attack at a hard-ridden 59 before he got to direct another. Sam needed work in the early eighties—he’d been fired from Convoy during postproduction, capping a decade of cocaine, alcohol, paranoia, cost overruns, and diminishing returns—and it came in the form of this Robert Ludlum adaptation. With its catchy Cold War milieu, surveillance-culture sheen, and precariously hairpin plot, the film is more obviously topical than peak-period Peckinpah; the film’s sensationalism is a matter of its super-contemporary hook, rather than the more eternal, atavistic violence that was Peckinpah’s great subject.

David Weddle, in his invaluable Peckinpah biography If They Move . . . Kill ‘Em! , writes that the director “gritted his teeth” and turned in the product on time and on budget, despite fights with his producers. He wasn’t allowed to rewrite the script, or cast James Coburn, a proudly ornery bastard who’d sided with Sam in his fight against the producers of Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid; he was granted a single preview screening for his cut of the film, which was full of near-subliminal self-parodic asides, and from which producers Peter Davis and Bill Panzer (later known for Highlander) unceremoniously trimmed half a reel or so. (Anchor Bay’s two-disc DVD does include Peckinpah’s preview version, taken from a low-quality video recording; I’ll be talking about the theatrical cut here, the compromised and interfered-with vision of which seems appropriate given the issue guidelines.) Reviews at the time ranged from the bemused to the flabbergasted, and if anyone’s made a passionate auteurist case for the film since, I guess I missed that article. Weddle does note, perhaps a little wryly, that the film did quite well in Europe and on the home-video market.

In A Cinema of Loneliness, Robert Philip Kolker complains that at the end of The Wild Bunch, Peckinpah’s “sympathies remain with the self-centered group of men whose vitality only embraces death” (or at least he so complains in the original edition I read in my high school library—this line, like the whole chapter on Francis Ford Coppola, seems to have gone missing from subsequent editions). This, or something like it, is the generally accepted dismissal of Peckinpah, and while such a point of view ignores the “vitality” of so much of his work—Ida Lupino’s earthy entrance in Junior Bonner, Steve McQueen and Ali MacGraw’s future-perfect swimming-hole canoodling in The Getaway, or any time Strother Martin and L.Q. Jones are onscreen together—it’s at least true of the director at his worst, at his most falsely macho and nihilistic.

Howard Hawks’s famous late-in-life bragging to an interviewer about advising John Wayne to “make three good scenes . . . and don’t offend the audience the rest of the time” was a typical Hawksian bit of macho pretension-slaying, equal parts prideful and tossed-off. In The Osterman Weekend, Peckinpah makes at least three good action scenes, daringly juxtaposing his trademark slo-mo bloodletting with contemporary suburban banality, but the presence of these excitements, amidst such a silly and mechanical product, suggests a kind of cynicism Hawks only kidded about—and a validation of Kolker’s criticism. Everybody’s slumming here, but the movie cuts a good, violent trailer. The commercial imperatives of the Peckinpah myth—the action, disturbingly elegiac and hypnotically syncopated—are delivered. But then, so too are stray moments of craft, color, and nuanced, surprising, rueful empathy. Vitality, in other words—though not nearly enough for The Osterman Weekend to fully rebut Kolker’s claims on its own.

Really, if there’s any valued auteur whose contribution to The Osterman Weekend is inexplicably, worryingly bad, it’s not Peckinpah but screenwriter Alan Sharp, who reportedly expected his script to be rewritten extensively—an arguably reassuring explanation for how the name of the guy who gave us Night Moves ended up attached to a film full of inauthentic psychologizing, empty reversals, and dialogue at different points flatly expository, canned tough-guy, politically bloviating, and off-topic pretentious.

We begin with John Hurt and some blonde whispering in French amid rumpled sheets; when he leaves to shower, she starts to masturbate, and then, as in some Brian De Palma stroke fantasy, uniformed men break in to clamp a hand over a mouth and stick a syringe into the side of her nose (they don’t leave a mark). The scene has the pixilated, anemic colors and abyssal black backgrounds of closed-circuit TV; much of the film is shot from the perspective of security cameras, and for that matter Peckinpah’s frequent DP John Coquillon nails the crisp, wood-paneled, thick-carpeted, chino-toned look of monied Reagan-era decor—the film, like most TV shows of the era, takes place primarily in up-to-date and personality-free interiors (even Lalo Schifrin’s score, all warm synthesizer and saxophone, feels small-screen).

This snuff-like cold-open’s relation to the movie that follows is immediately buried in a torrent of pay-no-attention exposition, laid out for hammy Burt Lancaster’s national security state true-believer megalomaniac Maxwell Danforth. The crucial “Omega File” dossier, pieced together by Hurt’s spook Lawrence Fassett for his benefit, is assembled with ease: obvious conversations between three Soviet sleeper agents and their heavily accented handler, recorded with pristine audio and video in public places. More surveillance is ordered; by coincidence, these three Berkeley buddies have their annual reunion weekend upcoming at the home of their old chum John Tanner.

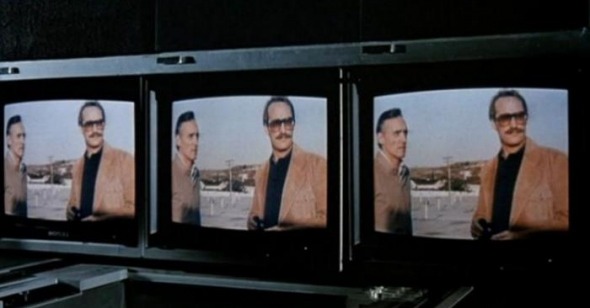

Tanner is a telejournalist first seen nonpartisanly ripping a general on his perhaps ironically titled show Face to Face; he agrees to let Fassett rig up his suburban abode with hidden cameras in exchange for the promise of an interview with Danforth (who himself practically salivates at the prospect). The Osterman Weekend is fashionably skeptical of the mass media: once Tanner’s house is wired with hidden cameras, Fassett sits in an off-site control room, his studio, cuing clips to play for Tanner on the TVs he has in practically every room, or addressing him directly, like a newscaster. He also gets to watch Tanner and his wife have sex on the closed-circuit, and to watch Tanner watch his friends have sex on the array of monitors he has in his den (apparently unconcerned about detection); Fasset rewinds to see instant replays of fights, and channel-surfs between a baseball game and Tanner fighting an assailant with a baseball bat. His final, sonorous monologue (after he’s already gotten to jiggle his arms and make a puppet-master joke) is an ironic harangue about entertainment and distraction, though the film hardly makes a case for the inherent synthetics of live security footage.

The cameras in place, the three friends, two with wives, converge on the comfortable one-story suburban house where Tanner lives with his wife and preteen son, who bow-hunt together (his friends are all childless; it’s hard to tell how the kid is keeping himself occupied when the plot doesn’t call for him to be threatened). Dennis Hopper is edgy as Richard Tremayne, a bad doctor with a cocaine-addicted wife; Chris Sarandon is pathetically unmenacing as the vaguely streetwise banker Joe Cardone; and Craig T. Nelson is the eponymous Bernie Osterman, a TV writer-producer well-versed in judo and other manly arts (drinking, mainly).

The movies sometimes give us moments that transcend whatever critical training or analytic biases we bring to them, and the discovery of a career performance from Craig T. Nelson is one of those moments—you’ve just got to go with it. There is, first of all, his mustache, as hilarious as Tom Selleck’s but silkier, more tapered, like a Civil War general’s. His general appearance, and cultivated persona, is burly and conservative, like Friday-night TV at its least adventurous, but Nelson’s funny and self-aware here, arrogant and dashing with a self-mocking confidence in the way he mumbles his lines away, as when he knows his charisma is wasted on the highway patrolman who’s pulled him over, or the way he makes himself fun and foolish with Tanner’s son, shouting “Onwards!” as he settles onto his toy wheels. The pleasure of his performance is in its ease, which is entirely at odds with the contortions of the story.

Because the CIA has tipped off Tanner’s house guests in an effort to intimidate them ahead of the weekend—possibly blowing Tanner’s cover—all the cards are on the table by the time Osterman, et al., arrive for the weekend. As such, the uneasy camaraderie of old friends seem beside the point, as does the symbolic spillover of horseplay into violence (though the latter is at least well-shot: as a two-on-two water-basketball game devolves from hard fouls to hand-to-hand combat, Peckinpah hyperbolizes the action with slo-mo, a memorably visceral treatment of a scene familiar from may other films about the barely contained aggression of old pals). With everybody’s secrets already mostly out in the open, Peckinpah keeps dramatic tension up with hup-hup up-tempo editing of the old-times banter, so you don’t have time to wonder how the friends ease back into their rhythms, or have to endure impossibly written and played scenes of doubletalk and suspicion. Everyone gets his or her close-up—the coverage is assured, and a bit dizzying—and the oblivious wives carry much of the downtime. As Mrs. Tanner, Meg Foster uses her striking icy blue eyes to appear dialed-in, rather than dead on the inside, as she did in They Live (“That blue-eyed bitch!” someone exclaims late, more admiringly than intended). Of the houseguests Cassie Yates is whiny as Sarandon’s wife, and Peckinpah’s camera favors Helen Shaver as Hopper’s slutty trophy bride, Virginia, who has a lascivious word for everyone, does bumps at the dinner table for attention, and skinny-dips blithely in home movies of weekends past, that everyone is finally that everyone’s buzzed and friendly enough to watch.

The home-movie pool frolics are a shrewd evocation of middle-aged hedonism—not least because these false friends are watching their own greatest hits, and maybe also because of the appallingly proprietary way the husbands have of passing their naked wives around, mirrored in Peckinpah’s own casual ogling. But there’s also an unexpected, odd tenderness to Peckinpah’s treatment of Virginia. Initially a flat character, given a single entendre or a close-up coke snort every so often to mark her place in the script, she takes a sudden plunge into a new dimension of excess. When, late in the film, the shit hits the fan and the house guests flee, Peckinpah cuts from a brawl back to Virginia in the bathroom, her lower face suddenly smeared with powder, and what had been a carelessly hateful characterization makes a play for pathos: she’s singing a children’s song about Jesus in a thin, lost voice. Cheap and maudlin, sure, but it’s also bluntly effective, to see this one-note character get stuck desperately on repeat—not a bad way of describing addiction. There’s probably some grim, forgiving recognition going on here with Peckinpah, who was, Weddle writes, struggling—not always successfully—to curtail the cocaine habit that had swallowed up so much of the last decade of his life.

It’s because of his addictions that Peckinpah’s later films have well-earned notoriety for slack stretches, punctuated by curdled, ill-considered sequences and occasional bolts of genuine inspiration. (One of his worst-ever scenes, the whore-gy wherein Coburn’s weary, desensitized Pat Garrett needs “four to get it up and five to get it down,” is an apt metaphor.) And indeed, the action sequences of The Osterman Weekend—the postproduction of which saw Peckinpah fall precipitously off the wagon—are the only scenes in the movie that really make sense.

The film’s two best scenes are, as eternal formula dictates, an early chase and a climactic shootout. Before the weekend begins, Tanner’s wife and child are abruptly carjacked—by whom? The multiple motives the film encourages you to construe are all equally elaborate and nonsensical, and Peckinpah spends as little time as possible on them—and Tanner steals an elderly couple’s pickup truck and gives chase. The lead car is the family’s wood-paneled station wagon, driving along what appears to be an access road leading out from an airport parking lot; Peckinpah’s montage, as the cars elude traffic, 18-wheelers carrying logs, and hurtling freight trains, mixes real-time with multiple rates of slow motion, intercut rapidly for a jarring, stop-start effect. The sound editing matches every bleating horn, smashing windshield, and screeching tire with its onscreen source, even if for only a few frames at a time, forming a weirdly abstract soundscape of industrial noise that also evokes the multiplanar buzz of the freeway.

![]() The big showdown happens, delightfully, around Tanner’s in-ground pool, with facing deck, guesthouse in back, and woods sloping up on the side. Tanner and an ally are pinned down by a handful of black-shirted extras with laser-powered assault rifles—Peckinpah gets a lot of use out of one slow-mo shot of smoke billowing out of the barrel below the red laser sight—diving across the shot-up desk set and then keeping their heads under water, dodging little whirlpools of bullets until Foster takes out an assailant with a bow and arrow.

The big showdown happens, delightfully, around Tanner’s in-ground pool, with facing deck, guesthouse in back, and woods sloping up on the side. Tanner and an ally are pinned down by a handful of black-shirted extras with laser-powered assault rifles—Peckinpah gets a lot of use out of one slow-mo shot of smoke billowing out of the barrel below the red laser sight—diving across the shot-up desk set and then keeping their heads under water, dodging little whirlpools of bullets until Foster takes out an assailant with a bow and arrow.

Peckinpah’s eye-blink editing of slow-motion action, in which time is at once fleeting and dilated eternally, ensures that stray images linger in the mind. His innovations in montage are maybe less of the moral proposition we tend to talk about—challenging us with the aestheticized “bullet ballet” of violence—and more of a simple technical innovation (albeit one in touch with something deep about time and memory and the mechanics of cinema). He slows down to marvel at the mismatched assortment of imagery—suburban luxury, high-tech and low-tech weaponry—and luxuriates in showing Foster lining up her shot with those arctic-blue eyes, temporarily at least, inverting the gender dynamic. (As when the kid shoots William Holden at the end of The Wild Bunch, violence is a universal, rather than male, impulse.)

Briefly, in these two set pieces, Peckinpah’s recurrent themes feel fully integrated into the world of the film—our world, at least in 1983, of cookie-cutter exurbs and shallow post-McLuhan media commentary—even deepening it. It’s not sad and inevitable that Peckinpah’s last movie only finds meaning in violence and death—rather, Peckinpah’s last movie shows his ragged, fitful genius for convincing us of the profound ways in which violence and death continue to interweave with we might choose to call our lives.