Simply the Worst

For our thirtieth symposium, we asked our writers to consider at length the movie that they believe to be the worst in a single filmmaker’s career. However, “worst” could be applied in any way our writers interpreted it.

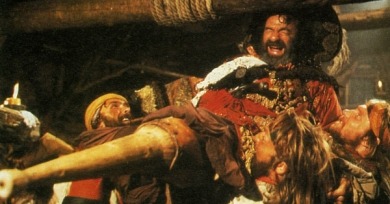

Perhaps the gutter-level gags and inert humor of Pirates afford a truer picture of Polanski’s essential perversity than the auteurist literature—where the film usually merits little more than a passing reference—seems to suggest.

Were Altman’s alarm bells not triggered by these ostentatious attempts at self-definition, or did he simply not bother to pursue this trickier line of satiric inquiry?

With its catchy Cold War milieu, surveillance-culture sheen, and precariously hairpin plot, the film is more obviously topical than peak-period Peckinpah; the film’s sensationalism is a matter of its super-contemporary hook, rather than the more eternal, atavistic violence that was Peckinpah’s great subject.

It can ill afford to release a movie on DVD, targeted at children, that could be accused of racism; at the same time, it would be foolish for Disney to completely shutter “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah.” So we end up in an uncomfortable place: the movie exists, but it doesn’t . . .

The film is desultory, employing aggressive editing not for exhilaration but in the service of sensory assault. It entraps its actors rather than letting them achieve liftoff. Cabaret and All That Jazz have urgency; Star 80 feels like a movie Fosse stopped wanting to make almost immediately after he rolled camera.

His approach has worked well for stories predicated upon their visuals, sagas that relied on plot and only flirted with abstraction, but when it came to adapting The Lovely Bones Jackson’s insistently literal approach resulted in both the worst film of his career and a fundamental misuse of his beloved medium.

“I had progressed from being a person with a literary vision to being someone with a visual vision,” he told Kevin Jackson. “And with that film I tried to back off, I tried to suppress my new literacy.” The result of this suppression was a film of bland visual ambition without a balancing surfeit, or even modicum, of ideas, wit, or poetry.

Perhaps Wong’s heart softened after so many years of denying spectators that one moment of lasting desire we so often coveted in his other, greater films. Or perhaps, as some thought, what seemed nonchalant in Cantonese becomes obvious and sentimental cheese in English.

Critical pans aside, Vanilla Sky was a financial success, something I’m willing to admit has more to do with the fact that it’s a star vehicle from the height of Cruise’s career than the fact that it’s far and away Crowe’s best, most ambitious film.

A recent viewing of Elia Kazan’s largely forgotten 1969 drama The Arrangement had me wavering between fanboyish reappraisal and head-slapping censure as it oscillated from courageous to ridiculous and back.

Rated the lowest of all Coen films on Rotten Tomatoes, and generally spoken of with embarrassment by fans who see it as the nadir of their career, the 2004 version of The Ladykillers—a loose remake of the 1955 British comedy—makes the best case by which to come to terms with the siblings’ thick, often impenetrable, ironic humor.

I prefer to think that Hughes knew exactly what he was doing when he made Curly Sue, his parting letter to an industry that both nurtured and exploited him. Beneath the film’s thick layer of sentimental goo lies a deeper cynicism about the nature of wealth and happiness in an otherwise uncaring world.

Replicating Tenenbaums’ bursting-at-the-seams mise-en-scène, The Life Aquatic is in every way a bigger affair. Tenenbaums conquered New York; Aquatic conquers the oceans.

Redeeming the film in full isn’t part of the plan—In the Cut remains upon repeated viewings something of a mess—but it’s still a fascinating work to examine.

I think it’s safe to say that this would be enough for most of us to label The Keep a complete failure because it fits all the standard criteria by which movies (at least those positioned to make an immediate dent in the culture-cum-marketplace) are judged. Yet it still manages to cast a mesmerizing spell.

It was made right in that not-so-sweet spot in the middle of the decade, when audiences refused to see anything that didn’t feature Julie Andrews spinning on a mountaintop and when producers were trying to appeal to younger, more progressive audiences without giving up on their waning stars and once tried-and-true formulas.

For a legitimate cinephile, intent on exploring the boundaries of cinema’s appeal, the matter of Wood’s technical competence is not structurally relevant to an appreciation of his work.

Who knows what lines of dialogue, what images, are meant to convey humor: People dressed like garbage cans, dancing? A close-up of oven-burnt sausages? A man “meditating” in lotus pose on top of a car? Hippies singing a round of “Ten Little Indians” on a Ken Kesey–style school bus?

It is a film maudit not because it suggests a filmmaker struggling with his material, but because the film falls short of the mark even while it remains so close to Bergman’s other work. In this way, it’s the film maudit at its most maudit: the self-parody.

Anything Else has been labeled by some as an attempt on Allen’s part to bring his artistry to a more youthful market, but I wouldn’t give him that much credit for business savvy, or interest in much of anything that’s happened past the 1950s.