He’s with the Band

Justin Stewart on Light of Day

The line of Paul Schrader’s output as a director is craggy and deformed, marked by multiple junctures when he has seemed to forget what he’s doing, or why he’s been so valued. A part of his special appeal as a director is his willingness to risk failure and embarrassment. The risk is obvious in 1988’s endurance-testing Patty Hearst, or 1985’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, a radically structured biopic of the Japanese writer that makes few overtures to general audience appeal, and it’s barely less so in something like 1992’s Light Sleeper, with its rampant gloominess and the soundtrack’s almost avant-garde use of Michael Been’s overbearing art-folk. Schrader doesn’t fail when he pushes his style to the limit like this, or even when he proves repetitive, making his umpteenth Taxi Driver variation, or repeatedly referencing Dante Alighieri’s infatuation with his muse Beatrice, or borrowing the ending of Pickpocket one more time. He has failed when bowing too insecurely to convention.

Because it was released between the fascinating Mishima and challenging Patty Hearst, 1987’s Light of Day can’t help but stand out as a blemish on Schrader’s strange résumé, though his now 34-year-old directing career has seen lower lows. It doesn’t get worse than 1999’s Forever Mine, about a cabana boy (Joseph Fiennes) who seduces the wife (Gretchen Mol) of a business jerk (Ray Liotta) and gets shot in the face and buried alive for it, only to survive and carry out a protracted, dull revenge under the guise of a romantically scarred Latin attorney called Manuel Esquema. This fifth-rate Alexandre Dumas knockoff is below Schrader in a way that his God’s Lonely Man retreads, though no fresher, aren’t, because he’s made the latter terrain his own. Auto Focus (2002) is conventionally designed and structured, but its subject (a horny, murdered sitcom actor) is so pathetically tawdry that there’s style-subject friction, added to one of Willem Dafoe’s most unsavory creations in the lizard-like joyboy Carpy.

When the former critic shelved his initial calling to pursue screenwriting and directing, he said that he had to quell his critical faculties, “locking them out of the room” in order to focus on the capital-scrounging, actor-coddling, and practical technical feats that constitute moviemaking. His 1978 debut, Blue Collar, is well-acted and brashly funny, with some complex ideas about unions, but it was on 1980’s American Gigolo that Schrader, with help from Italian designer Ferdinando Scarfiotti (working as an artistic consultant), flowered as an artist with a unique visual identity. It would elude him a few times in the nineties, but his eighties run is formidable—with the exception of Light of Day.

“I had progressed from being a person with a literary vision to being someone with a visual vision,” he told Kevin Jackson in Schrader on Schrader. “And with that film I tried to back off, I tried to suppress my new literacy.” The result of this suppression was a film of bland visual ambition without a balancing surfeit, or even modicum, of ideas, wit, or poetry, and with a clunkily mismatched duo (Michael J. Fox and Joan Jett) in the lead roles of bush-league brother-sister rockers. John Bailey, who’d shot Gigolo, Cat People, and Mishima, was back, and while it’s true that Michael McKean punching a clock in a drab Cleveland factory didn’t call for the same cinematographic extravagance as a feral Nastassja Kinski slinking naked through a wet forest, Light of Day never looks better than what it probably should have been: a late-eighties TV movie along the lines of I Know My First Name Is Steven. There are some cozy, E.T.-like interiors, and some handsome exterior shots of Cleveland landmarks like the Euclid Tavern, but even a climactic deathbed speech by Gena Rowlands to daughter Jett, directly quoting from Schrader’s mother to him on her deathbed, looks ugly and plain (washed-out white) at a moment during which you’d expect crescendo reverence.

Schrader had been sitting on Light of Day’s screenplay for a few years before it was ever filmed, and after his artistically satisfying experience on Mishima (still the film of which he’s proudest), the return to this humdrum midwestern melodrama was anticlimactic. It’d staled. (Forever Mine was another script that moldered for years). It had initially been titled Born in the USA and meant to star Bruce Springsteen in the lead, before The Boss decided that he couldn’t be The Employee as a direction-taking actor. After seeing the screenplay lying on a table while writing music, Springsteen did help himself to the title for a huge hit song and album. Guiltily, he tossed Schrader the negligible song “Light of Day” free of charge for use in the newly named film.

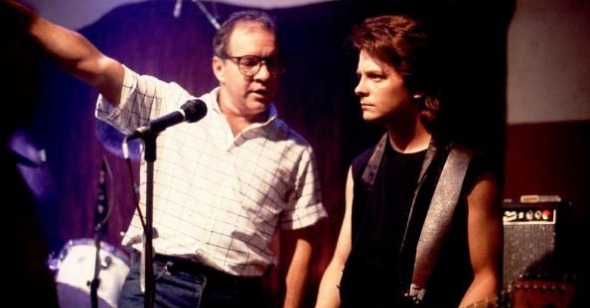

Though he credibly wielded that Gibson guitar in Back to the Future (inventing rock ‘n’ roll!), Fox, stuffed into oversized funky blazers and awkward vests and now with longer mullet, is no Raging Gigolo as the guitarist in the Barbusters. He looks so little-boyish in Light of Day that it’s almost upsetting to see him reading a Penthouse. With Springsteen in the role, we might’ve seen the bare-knuckle pushups or gravity bar pull-ups typical of a Schrader antihero. Not so with Fox. The actor understandably wanted to branch out and darken his Alex P. Keaton image, and he did it more successfully as the “Bolivian marching powder”-snorting Jay McInerney figure in Bright Lights, Big City, and as the conscientious soldier in De Palma’s Casualties of War (in which he was again outweighed by his wardrobe, though the kid quality was now appropriate). She looks nothing like Fox’s sister, but Jett acquits herself in her first acting role as Barbusters singer Patti, the single mother and agnostic family rebel who clashes with judgmental fundamentalist mother Rowlands. Jett botches any dialogue longer than two sentences, but the performance is a sight more naturalistic than Kristen Stewart’s posing turn as Jett herself 23 years later in The Runaways.

Light of Day is a strange case of both over-reaching and under-ambition. There was laziness in Schrader doing nothing at all stimulating visually, pointing at and shooting this soaper as if it was televised Royal Shakespeare Company. But his screenplay also tried too much; a colorful portrait of a lowly bar tab–earning Cleveland rock band would have been enough without the maudlin mother plot, which was about Schrader’s own mother in the way that 1979’s Hardcore (also defective, but with the merit of amusing ludicrousness) was about his father. In his later film Affliction, Schrader, aided by a mad James Coburn, explored defective parental relationships in an even narrower, more intense manner.

It wouldn’t be a Schrader film without the Calvinist sogginess, but a story solely about the mundane trials of the Barbusters would’ve better matched his lack of passion in the director’s chair. Rounded out by Thomas Waites as the drummer and Spinal Tap’s McKean as the family man bassist fond of Kentucky Fried Chicken picnics (with product noticeably placed), the band is lovably mediocre, and their colleagues in the Cleveland scene include the new wavers the Problems, featuring a young Trent Reznor on synth. Jett’s sellout graduation to national tours with cheesy metal band the Hunzz provides conflict enough without Rowlands’ mawkishness. What could have been simple pleasure is instead a miscast soap opera by a director misassigned to his own yellowed screenplay.