Fernando F. Croce

Herzog rarely misses a chance to leap on canoes, wade through sludge, and handle native arrows. When he faces the camera and bares his zeal and fears, one glimpses a man capable of directing as well as starring in Moby Dick.

A visual poet with a penchant for knockabout brawling, an idealist who gravitated to tales of melancholic loss, a notorious tyrant who cultivated long friendships, a nineteenth-century sensibility revered by many a hardcore modernist: John Ford, as they say, contained multitudes.

Face originated as part of a program of cinematic projects commissioned by and filmed in the Louvre . . . virtually each shot is an autonomous set piece, not so much building blocks in a linear storyline as visual-aural objects whose splendor works to mitigate the pervasive mood of despair.

The fluid border between contrasting universes has long been a motif in Selick’s work . . . and here he locates an ideal topography in the sulky, inquisitive, still unformed conscious of the eponymous “dizzy dreamer.”

It was once said that 1950s French film critics discovered Shakespeare by watching Orson Welles; how many budding film writers would later discover Welles by watching The Simpsons?

If The Wind Rises resembles Hollywood biopics like William Wellman’s Gallant Journey or John Ford’s The Long Gray Line in its decade-spanning structure and bittersweet tone, it is a singular showcase for the animation Miyazaki developed and perfected at Studio Ghibli.

Stanley Cortez’s cinematography is the glow of unbalance and neurosis, of fissures widening across psyches.

How massive the landscapes and castle chambers are in Akira Kurosawa’s 1985 epic, and how small the people in them seem.

Whether it’s her reportedly semi-autobiographical contributions to the screenplay or her off-screen relationship with Baumbach, Gerwig’s presence certainly figures vitally in the fact that Frances Ha is his most sprightly and least rancorous film yet.

The world in Suspiria is so threatening and unstable that colors glow with sinister intensity, the camera moves as if possessed, and natural sounds abruptly give way to jangly music—and that’s just the first minute or so.

No less than Merrick’s body and soul, his city is an entity at odds with itself. Graceful drawing rooms and soot-covered cobblestone streets, sparkling theaters and dank sweatshops: London may be on the cusp of the new century, but to Lynch this is still the land of Jekyll and Hyde.

Jam-packed with product labels and advertising slogans and clips from TV shows and movies, this is perhaps the Spielberg film most saturated with pop culture, as well as the one that most cannily illustrates the director’s ambivalence towards it.

The very title of Leone’s 1966 picture—the final panel of the Man With No Name trilogy that made Clint Eastwood an international star—subverts the usually Manichean moral conventions of the Western.

A recent viewing of Elia Kazan’s largely forgotten 1969 drama The Arrangement had me wavering between fanboyish reappraisal and head-slapping censure as it oscillated from courageous to ridiculous and back.

I wouldn’t hesitate to trade all the dimensional novelties of the latest Pixar picture for the single moment here when the screen is tilted this way and that to rouse the eponymous ursine protagonist out of bed, a bit of play with the frame that’s right out of The Navigator.

Most damning, though, is that the film refuses to answer the one basic question that must have come to mind for anyone who watched even the trailer: What’s her story?

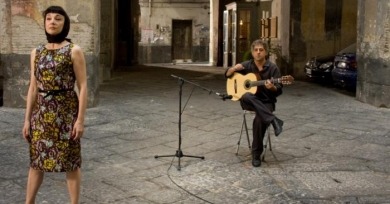

When one thinks of John Turturro’s films as a writer-director, the distinctive aspect that might spring to mind is not visual but sonic, a screen that vibrates less with strong images than with powerful aural groupings and collisions.

The resulting superficies often jangle and tingle, but the film’s vision of adolescence as fairy-tale espionage remains tastefully hollow, with its young heroine’s storms of violence increasingly becoming as calculated as any of Shirley Temple’s tap dances of pouting and sniffling.

It wasn’t until I moved to San Jose, California, that I first became aware of the idea of a community of fellow film-lovers. Up to then, movie-watching even in the most packed theaters had struck me as an essentially solitary act; these were secluded moments of thrilling discovery savored but seldom shared.

A rapacious, mercurial stylist, the painter-cum-filmmaker has over the years rarely hesitated to sacrifice storytelling coherence in favor of soaking in his characters’ vertiginous emotional states.