See It Big

Articles written on films showing in the Museum of the Moving Image's SEE IT BIG series, co-programmed by Reverse Shot editors Michael Koresky and Jeff Reichert

These are not castaways, but spirits in purgatory, their earthly possessions scattered around them like unwieldy memories of a past life. It is by mining the fantasy lives, the dreams and desires, of these preternaturally entwined women that Campion empowers them, makes them flesh and bone.

A big influence on me was Edward Hopper, because I look at his paintings and you have two or three objects in a room, but they combine to create a mood and a whole story. Suddenly a lamp become important, or a poster or a piano, and you choose more carefully.

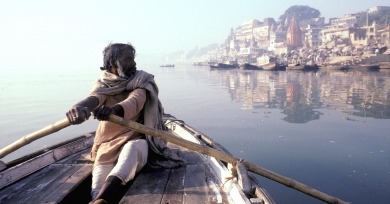

There is no narration, no translation, and no explanation for the dense thicket of ritual gestures that we are peering into, each of which, one can intuit, has behind it an entire system of symbolic meanings.

What if we could see what is actually on the other side of the world from where we sit? . . . Russian documentary filmmaker Victor Kossakovsky approaches these questions with a mixture of the digging child’s ingenuousness and the dogged explorer’s rigor and sense of purpose.

In Herzog’s 53-minute documentary on the Gulf War and its aftermath, the war begins and ends by the fourth minute.

Herzog rarely misses a chance to leap on canoes, wade through sludge, and handle native arrows. When he faces the camera and bares his zeal and fears, one glimpses a man capable of directing as well as starring in Moby Dick.

It is a film of indelible portraiture; the plot, as it is, exists largely to transfer our protagonists (and the camera) between congregations of winos, from gin mills to games of dominos around a flophouse common room’s pot-bellied stove.

Directors Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins (who translated his original stage choreography to the screen) fill their 70mm frame with ecstatic movement, operatic emotion, and brilliant color: it’s a dazzling Hollywood spectacle yet it still retains a remarkable delicacy and texture.

Brainstorm is a special-effects film in the sense that it contains more than its fair share of visual trickery but also because it’s concerned with the people and institutions that develop that trickery.

In honor of See It Big: Gordon Willis, the Museum of the Moving Image screening series co-curated by Reverse Shot, Michael Koresky and Jeff Reichert here pay homage to the great cinematographer by focusing specifically on his work in Woody Allen’s 1978 drama Interiors.

The case for this New York is made straightaway, in one of the most ravishing opening sequences in all of cinema—Gordon Willis’s sublime black-and-white static shots of the city, scored to “Rhapsody in Blue.”

The fluid border between contrasting universes has long been a motif in Selick’s work . . . and here he locates an ideal topography in the sulky, inquisitive, still unformed conscious of the eponymous “dizzy dreamer.”

How, these movies ask, might we come off in the eyes of the animals, objects, and fictional creatures in our lives? And how far can we go reconstructing our own lives—political, romantic, social, religious—by analogy with those of animals and toys?

In My Neighbor Totoro’s almost complete abjuration of kiddie movie standbys we have a small tale, simply told, but resplendent with details in its “pictures of ordinary days.” There is always a sense of ongoing life at the periphery of the events depicted.