Leah Churner

Like his celebrated 2000 debut, George Washington, Avalanche is slow and sparse, padded with meandering negative space.

Schnack and Wilson’s film implicitly pays homage to Altman’s seventies opus; like Nashville, Strangers is a backstage musical that simultaneously revels in and critiques indigenous cracker-barrel spectaculars, and frames the locale as a microcosm of American history and identity.

What if the old saying “You can’t go home again” has it backwards? What if we’re invisibly bar-coded to our point of origin, and we’re just spinning our wheels on the map when we try to leave, failing to shed the place we came from?

Killer Joe is like a fairy tale scribbled in the margins of a dirty joke book. Letts is a romantic of the Tennessee Williams school—it can’t be love if it doesn’t have claws.

Nashville is monumental entertainment: it opens with a new anthem for the Bicentennial (“200 Years”) and closes with an image of the American flag draped over a scaled replica of the Parthenon. In around three hours, over two-dozen characters converge in Altman’s panorama of the titular city.

Who knows what lines of dialogue, what images, are meant to convey humor: People dressed like garbage cans, dancing? A close-up of oven-burnt sausages? A man “meditating” in lotus pose on top of a car? Hippies singing a round of “Ten Little Indians” on a Ken Kesey–style school bus?

Typical of the writing and pacing in director Aaron Schneider’s film is a line from the funeral director’s assistant, drawn out for so long that sighs from the audience are audible between his pauses: “You wanna be at your funeral. Party. Alive? But. You can’t have a funeral if you’re not. Y’know. Deceased.”

Altman knows that architecture has an aural as well as a visual dimension, and Nashville is as much about soundscape as anything else.

We know from the serenade at the beginning of Starman that Bridges can sing and pick a guitar. But more than that, Bridges’s bluesy delivery (more Leonard Cohen and Tom Petty than Waylon Jennings) is truer to the contemporary sound of the progressive country singers who survived the seventies.

he core mystery of No Country for Old Men (both book and movie) is existential. The action may take place in a standing pool of blood, but the meat and gristle is the ugly side of surviving into old age: reckoning with cosmic disappointment from midlife to retirement.

Mathew Kaufman and Jon Hart’s documentary about Plato’s Retreat, American Swing, runs up against an old conundrum: the juicier the story, the messier the film. The leap from printed word to moving image removes the anonymity factor.

Documentary memoirs are getting out of hand. All too often these days what passes for nonfiction filmmaking is a training a tripod on one’s own face, and unburdening oneself with eighty minutes of babble about the motivations, misgivings, and frustrations of completing a film project.

Early in the documentary 30 Century Man, Scott Walker recollects his first visit to Sweden, in which he came to the horrific realization that vulgarity exists even among Scandinavians.

Each Advent, the moviegoer inevitably finds two holiday-anxiety genres under the tree: the child’s, in which an external force imperils a family, a group of orphans or a town and threatens to “stop Christmas,” and the adult’s, in which the threat to the sanctity of Christmas is the nuclear family itself.

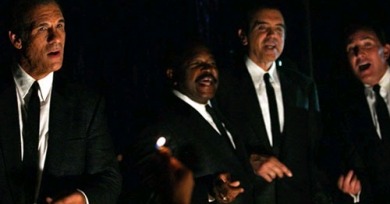

The premise of The Dukes is solid: the members of a doo-wop group, successful in the Sixties, are now loosely associated as losers, struggling to make alimony payments and working as line cooks in somebody's aunt’s restaurant.

If we could only harness the righteous indignation in and around Hounddog, we could heat our homes for free this winter.

Seen from the peanut gallery of non-Hollywood film history, today's "film versus digital" debate is more of a put-on than a sea change.

Clocking at roughly two hours, Honeydripper drags us through high cotton, Christian burials, and tent revivals, stopping along the way to allow each citizen of Harmony to relate a back story.

How did De Palma’s Scarface, a Hollywood extrapolation about minority machismo from 1983, become the apotheosis of gangsta symbolism?

Co-director Keith Fulton recently told indieWIRE that the greatest obstacle for Brothers of the Head was marketing it, which is a real knee-slapper.