Blood of the Beasts

By Lawrence Garcia

Afternoons of Solitude

Dir. Albert Serra, Spain/France/Portugal, Grasshopper Film

As an art of time, the cinema is not only capable of recording death but also has the “exorbitant privilege of repeating it,” per André Bazin. Not all deaths are treated equally, of course. Film history features endless examples of animal slaughter—from the seal hunt in Nanook of the North (1922) to the famed rabbit slaughter of Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game (1939) to the Parisian abattoirs in Georges Franju’s Blood of the Beasts (1949). But beyond the realms of war reportage, snuff films, and edgy exploitation fare, documents of human death are, for rightful ethical reasons, a rare occurrence. Those art films which are most proximate to human death, such as Wang Bing’s Mrs. Fang (2017) and Frederick Wiseman’s Near Death (1989), are often less about capturing the moment of expiration than about coming to terms with it—less about the interval in which death arrives than the intolerable expectancy and grief that exist on either side.

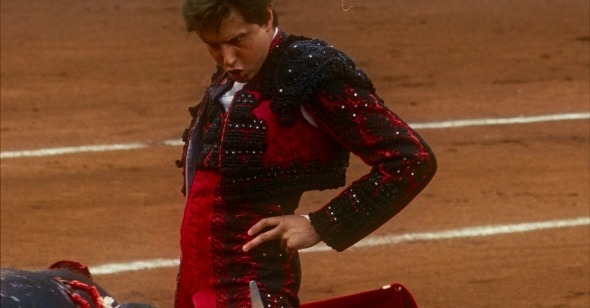

The cinematic spectacle of a bullfight is arguably unique, then, in that it combines the certainty of animal death with the morbid suspense of human mortality. Taking the tradition of Spanish bullfighting as his nominal subject, Albert Serra’s latest feature, Afternoons of Solitude, follows the Peruvian bullfighter Andrés Roca Rey in the rings of Bilbao, Madrid, Seville, and other cities over three years. But this overall span of time is largely occluded in the film, which mainly moves from one fight to another without marking when the bullfights are taking place. More significant for Serra is the temporality of the life-threatening encounters themselves, which wed the ritual of cinemagoing to the matador’s repeated decision—always potentially fatal—to enter the ring. As Bazin writes in a review of the 1951 documentary La Course de taureaux (Bullfight), referencing Ernest Hemingway’s nonfiction account of Spanish bullfighting: “On the screen, the torero dies every afternoon.”

For better or worse, Afternoons of Solitude does not display any interest in assessing the ethics of bullfighting as a cultural practice. No interviews or explicit reflections on the subject mar the film’s progression, whose rhythms are almost exclusively synced to the ritualistic repetition of Rey’s preparations for, and his actions within, the ring itself. We see car rides to and from the fights, where Rey is accompanied by his team, showered with a near-constant stream of aggrandizing remarks. We see the lengthy process of putting on his costume, as elaborate and specific as that of the most assiduous actor. And we see the fights themselves, which follow an ordered pattern of action that invariably ends with a bull’s carcass being unceremoniously dragged out of the stadium. Uninterested in proffering any moral judgments on bullfighting as a tradition, Serra instead investigates the perceptual, bodily specifics through which such a practice is both produced and sustained. What sort of environment is it where the decidedly unusual behavior we see—and which Serra renders deliberately alien and strange—can show up as predictable, expected, even natural? What is necessary to the internal sustenance of a tradition that from the outside looks brutal and even barbaric?

The film’s focus, then, is decidedly not on Rey as a biographical figure. To ask whether the film glorifies Rey is strictly irrelevant. Serra delves not a whit into the reasons he might give for taking up the tradition, as one finds, for example in Bullfighter and the Lady (1951), a fictionalized version of director Budd Boetticher’s own experience as a bullfighter. As Serra has remarked in an interview, “The film is almost an abstraction, separate from Rey’s reasoning or his choice.” Instead, Afternoons takes a perspective one might call naturalist, viewing the young matador not as an active agent so much as a mass of reflex and impulse.

That Afternoons takes such a perspective on Rey is confirmed throughout by the film’s judicious interplay between image and sound. Across the film, we become acquainted with the various ways in which the bull is manipulated until the final kill strike. So, when cinematographer Artur Tort’s camera occasionally follows the bulls across the field of action, we see how the plethora of noises, textures, and sights within the stadium incurve themselves around the perception of the bull, which is pulled this way and that by sheer, brute instinct. But at the same time, when the camera stays on Rey, as it does for most of the runtime, we become sensitive to how he, too, occupies a position analogous to that of the bull, responding by reflex to the shouts of his team, the audience’s cheers, and especially the taunts of combative onlookers. Serra’s decision to keep the audience almost entirely offscreen throughout, creating a disjunction between image and sound, only heightens this dynamic.

The approach to bullfighting one finds in Afternoons, then, is closer to that of a Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab film, such as Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor’s controversial Caniba (2017), than to what one might find in a biographical portrait or a Wiseman-esque institutional chronicle. The sycophantic remarks of Rey’s bullfighting team, which we hear across the film, may lead one to consider the social or institutional dynamics at play, to the question of whether the men are being sincere or opportunistic in their cartoonishly masculine praise. (Perhaps no film in history has ever included so many compliments about the size of a man’s cojones.) But arguably more significant to Serra’s aims than this question is the degree to which such behavior, so alienating from the outside, has over time been naturalized into the tradition, as integral to its functioning as the arenas, the costumes, the audiences, and the bulls themselves. We see this clearly when Rey, after miraculously surviving a vicious bull attack, says, “I got lucky”—a rare moment of dawning reflection that is immediately followed by remarks about his “abs of steel,” the “cowardice” of the bulls, and the “truthfulness” of the kill. In this moment, we see that to a large extent, the survival of the tradition depends on the suppression of any sort of reflection. From within the bullfighting tradition, the question of the relative sincerity of such statements cannot even be raised.

It is by examining the precarious sustenance of cultural tradition that Afternoons, despite being Serra’s first documentary, appears continuous with his prior work. The Death of Louis XIV (2016) observed the Sun King’s death by gangrene at a historically significant period when superstition was giving way to medicine. Likewise, the debauched proceedings of Liberté (2019), which centered on a group of aristocrats exiled from the court of Louis XVI, take place just two years before the French Revolution. This is also to say that Serra’s interests, here as before, have always been centered on the physical, bodily, and perceptual minutiae that sustain a tradition, as well as the transformations that result in its eventual demise. The key difference in Afternoon is that unlike the range of subjects he has previously treated—from Casanova and Dracula (Story of My Death) to the three magi (Birdsong) to Quixote (Honor of the Knights)—the practice of bullfighting is neither mythical nor apocryphal but remains active in the present day.

Perhaps this is not so great a difference after all. For if there is one certainty in Serra’s historically unstable films, it is the inevitability that entire traditions, languages, and ways of life will eventually pass on. In this sense, what Afternoons of Solitude anticipates and holds in suspense is not simply the death of one matador, but a time when no one exists to take ownership of the tradition it records.