Michael Sicinski

The more personal A Want in Her gets, the less it feels like a document constructed with a prospective viewer in mind, and so the result is edifying and intrusive in equal measure.

The film is an object that unfurls a bit like a complex piece of classical music. Zhao introduces forms and motifs in order to stretch them to the limits of intelligibility. Before you’re even aware of it, Periphery has already moved on to some other idea.

Forgoing any touristic impulse, Patiño takes his cues from filmmakers such as Peter Hutton and especially Mark LaPore, charting not only the people and places before him but also his fundamental distance from those environments.

The neoliberal present demands a new mode of realism, adequate to those structures of control that are cloaked by economic and informational avenues utterly inaccessible to all but the highest echelons of technocratic power.

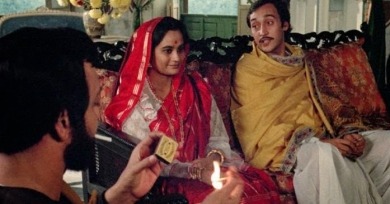

The Home and the World is focused on the efforts of two men with very different ideas about resisting colonialism and religious bigotry, but by opening the film with the town of Sukhsayar already in flames, Ray tells us in advance that their efforts are all in vain.

The reliance of outside texts and reference points is not only artlessly overt—it can strike a viewer as bound to a particular moment in film history, when cinema argued for itself on the basis of its having mastered a particular syllabus.

The Family confronts us with situations that are perfectly ordinary, without directing our interpretation. It’s only outside knowledge that complicates matters.

In Colo, three relatively ordinary people, a teenage girl and her two parents, are struggling to make ends meet. But by the end of the film, they are entirely new, having been shattered by trauma and reassembled into damaged, isolated individuals.

The screen, apart from some video scan lines and the usually-but-not-always present image of a refugee boat carrying 13 men, is little more than a blue rectangle, the Mediterranean Sea on a particularly sunny day.

With naked bodies slowly twisting and writhing in a thick, inky chiaroscuro, a hazy but unidirectional light giving definition only to the rounded forms and flexing musculature of the women onscreen, it is clear that Grandrieux has painting on his mind.

This mournful film takes the utopian aspiration of Communist dreams seriously, without overlooking the dangerous faults at their core.

Often the idea of the avant-garde implies a somewhat detached, contemplative mode of viewing, and this aesthetic stance is kilometers away from Gagnon’s bailiwick. Of the North seems to invite rubbernecking more than any conventional audienceship.

One could easily imagine German’s masterwork flickering through the gate in projection booths and then deposited in serpentine curlicues directly into a wet open pit, to be fermented like kimchi or composted like coffee grounds and eggshells.

Mascaro’s latest is his first foray into fiction filmmaking, but like his documentary work, is grounded in the realities of contemporary Brazil, particularly as experienced by citizens situated on society’s margins.