The Movement to Come

By Michael Sicinski

El Gran movimiento

Dir. Kiro Russo, Bolivia, KimStim

I.

In 1958, Bertolt Brecht wrote, “Reality alters; to represent it the means of representation must alter too. Nothing arises from nothing; the new springs from the old, but that is just what makes it new.” He was discussing the idea of realism, in particular its role in revealing the contradictions in society in order to foment social change. A cinematic form of political modernism emerged in the 1960s and ’70s, with the aim of taking up Brecht’s challenge: to find new ways of depicting the contemporary world, by analyzing it rather than reifying it. Although historically speaking this political modernism is most closely associated with Godard, other major filmmakers were also concerned with breaking apart the placid, self-evident surface of reality in order to expose social relations as the products of human endeavor. This group includes Fassbinder, Straub/Huillet, Nagisa Oshima, Marco Bellocchio, Glauber Rocha, Ritwik Ghatak, and many others.

This, of course, is well-documented film history. But a subsequent part of film history has not been nearly as well documented. That is the gradual evolution of realist political cinema away from the Brechtian model, and toward a more conventional form of realism, one that mostly conforms to the surface appearance of lived experience. From continuity editing and 19th-century literary narrative structure to the use of recognizably centered subjects as protagonists, this form of realism has several things to recommend it. For one thing, it tends to employ vernacular forms with which the target audience (the working classes) will be familiar. This kind of realism also has a longer tradition than the Brechtian variant. It is not difficult, aesthetically speaking, to trace a lineage from Émile Zola and Gustav Courbet to Ken Loach and the Dardenne brothers. Although this kind of filmmaking is sometimes considered formally and politically schematic, I am not making that claim, and actually admire much of the work under this category. These post-Brechtians have produced a critical realism that attempts to place recognizable characters—the underclass, usually—in narrative circumstances that follow the basic patterns of structured social relations: wage exploitation, racism, sexism, institutional neglect, religious bigotry, and the like.

It is a commonplace of contemporary critical theory that we are living in the era of neoliberal capitalism. As money and goods circulate with increased legal and technological freedom, human beings are subjected to greater and greater restriction of movement (immigration clampdowns, the global refugee crisis, the prison-industrial complex) and are gradually stripped of rights that had previously been, as the Founding Fathers put it, “self-evident” (privacy, bodily sovereignty, decent wages, housing, and healthcare, religious and sexual freedoms, and so forth). One of the fundamental conditions of neoliberalism, as both an economic and a political formation (the distinction is mostly academic), is a heightened technocracy, in which various forms of labor, information, and even capital itself, are contained within an electronic, virtual nexus. The radical disparity of access to this network of relationships is, again, self-evident. Undocumented day laborers must enter the system with traceable SSNs in order to be paid; they do not have access, for example, to the untraceable cryptocurrencies that enable the activities of the political and technocratic classes. Trade schools and community colleges are seldom able to provide cutting-edge technological training that would allow the lower classes to access the deeper strata of social relations at which those students’ very obsolescence is being engineered. And so on.

To return to the problem of cinematic aesthetics, it becomes necessary to envision artistic strategies for the representation of social relations that, by their very nature, are largely invisible, that leave no perceptible trace. Cinema has so far been stuck depicting effects without developing a language with which to articulate the mostly unseen causes. The Dardennes, for example, in Young Ahmed, show the street-level impact of Islamic fundamentalist politics, but cannot consider the fact that Daesh maintains coders, programmers, and image consultants on its payroll. Loach’s Sorry We Missed You does a reasonably good job depicting the impact of the gig economy of a single family, but cannot demonstrate the high-tech Taylorism with which panoptic algorithms dictate the speed and bodily movement of Uber drivers or Amazon warehouse employees. (To state the obvious, a corporation depriving its employees of the ability to regularly urinate is the ne plus ultra of Foucaultian bio-power.)

II.

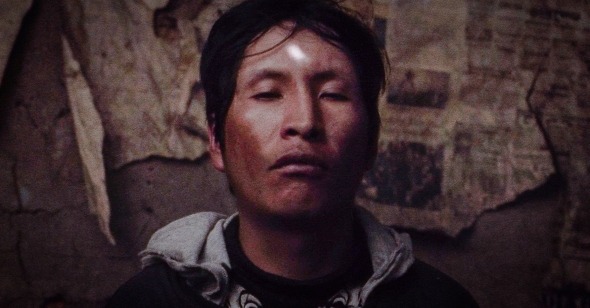

El Gran movimiento (2021), the second feature film by Bolivian director Kiro Russo, does not completely break with the dominant modes of political realism, at least not entirely. However, it provides a clear picture of a representational breaking point, a crisis that suggests it is necessary to devise new strategies for depicting social change. It is hardly coincidental that Russo’s new film picks up, to some extent, where his last film Dark Skull (2016) left off. In that film, we are introduced to Elder (Julio Cezar Ticona), a young man who attempts to become a miner following the death of his father. At the start of El Gran movimiento, Elder and his companions Gallo (Israel Hurtado) and Gato (Gustavo Milán) are part of a large group of unemployed miners who have walked from Huanuni to La Paz, to protest and state their grievances, as well as possibly find some work.

This journey by foot took the miners seven whole days. In addition to recalling the “great movement” of migrants up through Central America in 2017—that caravan that served as a popular bogeyman for right-wing cable news—the very facts of this trek suggest a herculean effort to put distance between the past and the future. Russo begins again with Elder and his adversity, but his troubles have now brought him to a very different place.

The narrative of El Gran movimiento starts out in a rather unremarkable handheld mode, placing the viewer in the middle of the miners’ street protest. In fact, a cameraman interviews Elder, asking him where they’ve come from and why. In terms of its formal and rhetorical address, the film nestled rather comfortably within the second political realist mode, combining the language of documentary with a fictional premise, occupying a hybrid mode that is itself a dominant aesthetic strategy in contemporary art cinema.

However, Russo actually begins with a highly controlled introductory movement, one that it is easy to initially misunderstand. El Gran movimiento starts with a wide-angle extreme long shot looking over the city of La Paz. The detail and focus are remarkable. We can see individual cars moving through streets, as midrise structures cluster together to comprise a dense, narrow urban environment. Russo depicts La Paz as a network of sorts, with stationary elements surrounded by the circuitry of transportation. We also see La Paz’s string of cable cars moving across the scene, cutting through the traffic and bisecting our view of the buildings themselves.

Slowly, we see that Russo is zooming in on this image of La Paz. We get closer to ground level, and eventually the cars and trucks blur into hazy atoms of film grain. At first we might simply think that Russo is giving as an establishing shot of La Paz, and using a twist on conventional film grammar to introduce his subjects, the miners. Instead of a straight edit, we “penetrate” the city and discover its human contents. But in fact, this is only the first of many such zooms. Russo continually provides a wide view of a given situation—a man sleeping in the woods or a group of workers struggling to unload and stack crates of broccoli—and takes us further into the image, disturbingly close to its physical constituents.

This is obviously a departure from the kind of political realism of Loach and the Dardennes, as well as a marked difference from the documentary/fiction hybrids that have become the newest iteration of that realist mode. There is nothing transparent about El Gran movimiento’s camerawork. These early zooms are brazenly directive. They call attention to what film theory once called “the point of enunciation,” that is, the director’s consciousness as materialized through formal decision-making.

Some of these shots—especially a zoom into a wall covered in the scraped palimpsest of wheat-pasted advertising posters—recall Godard’s work, especially Week-End (1967) and his later work with Jean-Pierre Gorin. But mostly, these zooms call to mind the work of structuralist filmmakers, in particular Michael Snow and Ernie Gehr. Snow, best known for his 1967 film Wavelength, consistently used camera movement and/or optical manipulation (zooms, swish pans, etc.) as poetic devices, intended to impress upon the viewer the intentionality of his or her perception of the film image. That is to say, for Snow, looking is always looking at, and seeing is always an act of consciousness oriented toward the world in an active manner.

Gehr’s work often expressed similar philosophical concerns, although unlike Snow, Gehr tended to apply these insights to the social problems of urban space. In films such as Signal – Germany on the Air (1987) and especially Side / Walk / Shuttle (1991), Gehr consistently trains his camera on the inner workings of cities, their organization, conduits of movement, and the mark they make on the natural environment. In the opening ten minutes of El Gran movimiento, Russo both zooms into and pans across the architectural density of La Paz, its situation in the Altiplano, and the broad divergence of its buildings as an instantiation of extreme economic disparity. Again and again, Russo examines La Paz as a kind of urban machine, pulling in closer to reveal spaces of homelessness, poverty, and low-level commerce.

Elder, Gato, and Gallo end up in a ramshackle outdoor market area, trying to pick up work and sleeping rough. But even before they secure their first odd job (moving sacks of grain for a merchant who underpays them), Elder starts to become ill. It starts with a cough, and he goes to see a doctor (Dr. Armando Ochoa) who is unable to help him. In time, his strength gives out, as though his body is physically rejecting the demands that his economic circumstances require of it.

Some commentators have remarked that Elder’s illness seems to have a supernatural or symbolic etiology, despite the fact that the doctor rejects this out of hand. (“To be frank with you, we don’t really believe in that anymore.”) And while contemporary art cinema has its fair share of symbolic illness, as the body’s expression of exploitation or malaise that cannot otherwise be expressed—e.g., Tsai Ming-liang’s The River (1997) or Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Cemetery of Splendor (2015)—Russo seems to be suggesting something else. The very fact that Elder’s illness cannot be explained, despite his work in the mines, his inhalation of rock and metal dust, and his poverty, which results in his sleeping outside in the rain and eating barely anything, indicates that the material plight of Elder and other workers like him cannot be seen. It is the invisible, unspeakable consequence of global capital, written on his body and the bodies of many others.

In a different vein, this crisis of representation, the fact that the forces controlling us are impossible to see with the naked eye, is also evident in El Gran movimiento’s depiction of Mama Pancha (Francisca Arce de Aro), a poor produce vendor who Elder encounters around the open-air market. She immediately addresses Elder as her “godson,” asking how he has been and what he needs. When Gallo and Gato ask Elder who she is, he admits that he has no idea. In previous economic regimes, kinship was a hallmark of authority, a way that the social world could be made legible. Even in Dark Skull, Elder assumes that he can fill his father’s role as provider. But in El Gran movimiento, kinship, while not exactly random, is highly fluid and subject to erasure. In a later scene, Mama Pancha finds another “godson,” the same employer who ripped Elder off. She claims to have been a friend of his mother, but there’s no way of knowing if this is true, if she is attempting a grift, or is afflicted with dementia.

Economic structures have ruptured our previous understandings of subjectivity, kinship, the wage system, as well as our ability to navigate space through cognitive mapping. The neoliberal present demands a new mode of realism, adequate to those structures of control that are cloaked by economic and informational avenues utterly inaccessible to all but the highest echelons of technocratic power. Throughout El Gran movimiento, Russo has employed unmistakable formal devices to inscribe these otherwise invisible relationships. In depicting La Paz as a kind of impersonal machine, the film positions Elder as both subject and object, someone trying to navigate the city by his own free will but constantly thwarted by his place within a larger system of oppression.

Toward the end of the film, Russo enacts a remarkable coup de théâtre, clarifying the stakes not only for this new moment of material privation but the need to develop a cinematic language adequate to it. As El Gran movimiento wends to its conclusion, Russo begins a rapid montage of scenes from earlier in the film: Elder at the protest, at the doctor, Mama Pancha and her friends at the market stands, random street scenes of La Paz—eventually the entirety of the preceding film. Doubling down on his structural formalism, Russo accelerates the montage, which eventually consists of millisecond-long images flashing before the viewer.

In the course of this sequence, Russo makes a stunning decision, a music quotation that most politically inclined cinephiles will recognize immediately. It is a section of the Alloy Orchestra’s score for Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), a passage that accompanies that film’s accelerated montage of Soviet city life. However, Russo has the score played on traditionally Latin instruments: trumpet, trombone, violins, and a snare drum playing a salsa beat. In this moment, El Gran movimiento brings its own mode of political realism to an unresolvable contradiction. Just as Elder and his companions traveled many miles to submit themselves to the neoliberal whims of La Paz, Russo dramatizes our historical distance from Vertov.

In other words, the contemporary city, as an entrenched network for global capital, cannot be depicted in a modernist “city symphony.” That is because, while Vertov aimed to depict the Soviet city as a product of human endeavor, neoliberal La Paz—its hard reality—cannot be reached by those who are subject to its network of control, including those filmmakers whose aim is to articulate those very conditions through cinema. We don’t know what comes next, or how those relations might successfully be visualized. But El Gran movimiento absolutely concludes an old, inadequate filmic regime.