Imogen Sara Smith

What starts out as an environmental parable, pitting respectful efforts to live in balance with nature against shortsighted corporate greed, turns into something far stranger and more disquieting.

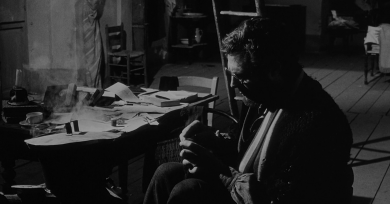

These are films about transients and transience, punctuated by soft dissolves and ellipses; sometimes people fade out of the frame like smoke, or vanish and reappear further away. Shimizu’s formalism and his humanism go hand in hand.

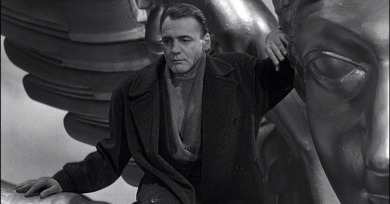

For migrants and refugees, the earth becomes a cruel obstacle course in which they gamble with their lives. The Dupes (Al-Makhdu’un, 1972), directed by Tewfik Saleh, tells a searingly specific tale of displaced Palestinians trying to cross the desert to Kuwait.

I took it all in with the wonderstruck child perspective the film cherishes, but over time some ambivalence has crept into my relationship with this beloved, hugely ambitious, and complex movie.

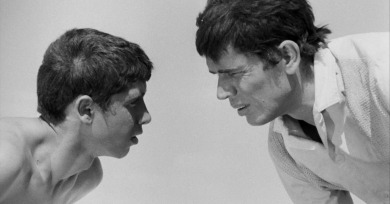

Among Mario Monicelli’s greatest gifts as a director was the expressiveness, specificity, and stubborn physicality of the worlds he creates. This textured, tactile realism is potent in The Organizer (1963), his epic tragicomedy about the nascent labor movement in late 19th-century Turin.

In his films, Petzold has always suggested the ways that our lives, like city plans, are shaped by historical forces, and also by narrative structures drawn from melodrama and the revenge thriller.

We read it not just for the light that smart writers can throw on cinema, but for the way that cinema, like the beam of a projector, lights up the minds of smart writers.

Naruse’s gracefully unobtrusive style is attentive to mundane details: table manners, tedious routines of housework or office culture. There are small pleasures to be found, but he also shows daily life as a process of erosion or weathering.

Colonel Blimp contains one of the wittiest and most inventive sequences ever devised to show time passing.

Almost cloyingly luscious, the cinematography feels perversely complicit in Ellen’s monstrous crimes. It not only makes her inhumanly beautiful, but endorses her inhumane perfectionism by surrounding her with beauty that is unsettlingly perfect.

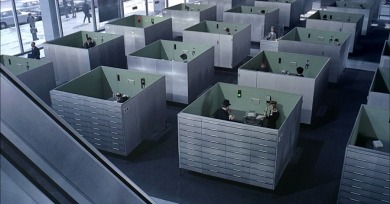

When asked why he chose to make Playtime in 70mm—the first and only time he used the costly format—Tati responded that it was necessary to capture the scale of modern buildings, since he intended the décor to be the star of the film.

“A singular being in a plural world” is how Jean Cocteau described the French director Jean Grémillon. His films are sensitive to the tensions between individuals and communities, between the cyclical patterns of daily life and the private obsessions or conflicts that break these rhythms.