Lost Time

Imogen Sara Smith on The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp

What is “real time”? In cinematic terms, the phrase means that events are recorded without elisions or interpolations, so that time in a film is synched to the time you spend watching it. But our experience of time is more complex than what can be measured by the ticking of a clock. The present is always invaded by the past and the future. Our minds, occupied with memory or speculation, have scant capacity to observe the moment-by-moment progress of the now as if we were cameras.

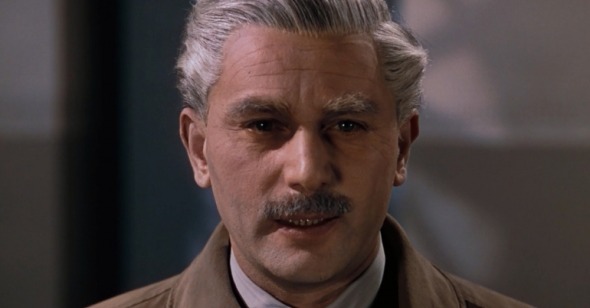

Many aspects of time, from the dry precision of date and hour to the flights of remembrance and regret, are distilled in a single scene from Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943). The setting is a British refugee office during World War II, where the German émigré Theo Kretschmar-Schuldorff (Anton Walbrook) pleads his case. Opening with a close shot of a typewriter filling in a bureaucratic form, the scene builds to a majestic speech, filmed in a single three-and-a-half-minute take and delivered by Walbrook with hypnotic intensity, in which Theo explains why he came to England. Having humbly and correctly answered the interviewer’s questions, he finally confesses: “The truth about me is that I am a tired old man who came to this country because I was homesick.”

The camera begins to creep toward Theo as he talks about his English wife, their grief at their sons’ defection to the Nazi party, her death, and his longing to return to her homeland—where he had been before only as a prisoner in the First World War. The camera closes in on Walbrook until he fills the frame, and stays there unblinking, just as the viewer is drawn in and held rapt by his passionate interiority. He recalls happening upon the site of the sanatorium in Munich where, decades earlier, he had met his wife and the Englishman Clive Candy—the eponymous Colonel Blimp—and being overcome by nostalgia as he revisited the place. This memory of a memory describes layers of time, and the way that the most distant events can burn brighter than current ones. Theo’s evocation of the English countryside is poignant not just because it is connected with his dead wife but because the green hills and winding streams he conjures are rarely seen in the film. The way that all of this—a landscape, a nation, marriage, death, old age, the quiet violence of time and the curt brutality of history—is summoned through words alone, within a small drab office, goes to the heart of the film’s greatness. For all its cinematic bravura, its essential genius is narrative. It is the crowning masterpiece of screenwriter Emeric Pressburger, a Hungarian Jewish escapee from the Nazis who put his own love for his adopted land into Theo’s speech. (Austrian-born Walbrook was another anti-Nazi émigré to England.)

David Low, the New Zealand–born cartoonist who created Colonel Blimp, a buffoonish caricature of the military old guard, marveled at Pressburger’s “phenomenal power of storytelling,” quipping, “He left Scheherazade standing.” The comparison was apt. In the 1001 Nights, Scheherazade preserved her life by leaving her stories tantalizingly incomplete, so that the sultan would let her live to continue them. Part of Pressburger’s brilliance was to build into his screenplays chasms that the mind has to leap, and blanks that the imagination has to fill. These leaps create much of the joy and surprise you feel watching movies by the Archers, as Powell and Pressburger named their writing-producing-directing partnership. It is not the arrow or the target that provides the deepest thrill, but the flight through space.

The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp is constructed around a series of ellipses. On the surface the film is an overstuffed epic, following career military man Clive Candy, later Major-General Wynne-Candy (Roger Livesey), from the turn of the 20th century to the Second World War. But, again and again, big events happen off-screen. We don’t see people fall in love or get married or die, we only hear what happened after the fact. The first and most audacious instance of this method comes when Clive, in Germany after the Boer War, fights a duel with Theo. There is a long and comically elaborate build-up, sketching in a whole world through the fastidious, gentlemanly protocol governing the fight; but as soon as swords are drawn, the camera floats up to the ceiling of the gymnasium, up and out into the snowy night where English governess Edith Hunter (Deborah Kerr) sits in a carriage nervously awaiting the outcome. We wait with her, and the film teasingly delays the revelation that both men have not only survived but also become friends.

When Edith meets Theo, we see nothing between their initial attraction and the announcement that they are engaged. Later, we will not see Clive meet and court his wife Barbara Wynne (also Kerr); we will not see either Edith or Barbara sicken and die. These lacunae create a palpable sense of years passing and of loss, because so much is already over by the time we know about it. The gaps also give the film its powerful emotional resonance. Most of the story unfolds in flashback, as the aged General Wynne-Candy—devastatingly humiliated by a young soldier who mocks him as a useless relic—looks back on the course of his life. So the elisions in the story suggest Clive’s obliviousness to his own deeply buried feelings, or his inability to let his mind touch the most painful things. By not dramatizing major events, the film subtly creates a feeling that Clive is a man who, for all his heartiness and uncomplicated solidity, has missed out on his own life.

Colonel Blimp contains one of the wittiest and most inventive sequences ever devised to show time passing—shaming the movie clichés of pages leafing off a calendar or years marching by with glimpses of newsreel milestones. The emptiness of Clive’s life in the decade after his return to England, where he realizes too late how much he loved Edith, is conveyed by the proliferation of big-game trophies on the walls of his house. Each head materializes with a bang, annotated by a label showing the year and place where the unfortunate animal met its end. Clive is, quite literally, killing time.

One way of defining time, that intangible and mysterious dimension, is as a measurement of change. In a film spanning four decades, the passage of years is illustrated by Livesey’s transformation from hale young soldier to dimming middle age, with thickening waist and thinning hair, to the cartoonish image of the bald, walrus-mustached, tubby general in the Turkish bath. Yet Clive Candy’s tragedy is his inability to change. When, as an old man, he confesses to Theo that he never got over losing Edith, what might sound melodramatic is a simple statement of psychological truth. Cleverly underlining this truth is the triple casting of Deborah Kerr as Edith, Barbara, and Angela (aka Johnny), Wynne-Candy’s spunky driver in the WWII scenes. We never see any of her characters age, because Clive’s ideal of womanhood never evolves. When he shows Theo a portrait of Barbara, he expects his friend to be astonished by her resemblance to Edith; but Theo watched his wife age, so her youthful image is not frozen in his mind as it is in Clive’s.

Repeated images and motifs stitch together the film’s tapestry, at times almost too neatly. Standing on the doorstep of their London house, Barbara makes Clive promise never to change, “until the floods come, and this is a lake.” Naturally, we don’t see the bomb that destroys the house, only the dusty aftermath, with a rhino’s head being pulled out of the rubble, and then water filling the bomb-crater. Rhyming with the pool Clive plunged into at the start of the flashback, this lake is a physical lacuna (the words are related), the hole left by all Clive has lost. Gazing down at a dry leaf drifting lightly on the water, he has his one piercing moment of understanding: that the world has passed him by, the floods of history have swept away all his certainty and bluff confidence, leaving him an irrelevant husk, like that fallen leaf.

Even when it is standing, Clive’s house—packed as it is with Edwardian bric-a-brac and souvenirs of battles, guarded by a stuffed grizzly bear that holds a tray for the mail—feels oddly empty. Home in Colonel Blimp is an idea, a goal, but somehow never a reality. When Clive returns to England from Germany and makes the mistake of taking Edith’s disappointing sister out on a date, they go to see a theater adaptation of The Odyssey, and watch a scene in which the gods argue about whether or not to let Odysseus go home to Ithaca. At the end of World War I, Clive sits in a car in the blasted, lifeless battlefield, and suddenly hears the birds singing as the guns die down. “We can go home,” intones his Scottish driver Murdoch (John Laurie), “We can all go home.”

It’s not that easy. Theo’s speech in the refugee office implies, without saying it openly, what Tennessee Williams wrote in The Glass Menagerie: “Time is the longest distance between two places.” Theo can return to England, but never to the days when his wife was alive. Film, however, can rewind or replay, slow down or speed up time at will, as Colonel Blimp does with its flashbacks, its way of skipping over years as a stone skips over a pond. The challenge then is to make cinematic time feel like real time, to capture the irreversibility of age and loss, the way the past is at once inescapable and unrecoverable. This can’t be accomplished by any trick of the camera. Yet it can be done when, as in the scene in the refugee office, we are confronted, with the greatest simplicity and force, by the homesickness of one tired old man.