Take Six: Reverse Shot in Time

When Brick and Mirror was released in Iran, it was harshly condemned for its bleak ending, slow pace, and lack of plot. But through an episodic narrative structure in which our male protagonist encounters a variety of people and situations, Golestan creates a network of peculiar intimate encounters.

Time is the central component of the oeuvre of Lav Diaz to date—their length is why it works, why his films are so special and also why many choose to stay away, if they even get the opportunity to see them at all.

It’s all over in the space of a few seconds, but everything about it is “off.” The sequence feels wrong because of the length of the takes. These few seconds of screentime, fleeting though they are, take too long to unfold.

In Lubitsch’s movies, love simmers and strains, but it is equally likely to materialize within the space of a single gesture.

Its unhurried pace and loose structure make it easy to mistake for a tribute to a life well lived, a leisurely exercise in smelling the roses.

For a brief instant two distinct realities share a coherent space and time. The two sides never interact, they don't have to; here it's enough for them to brush up against each other.

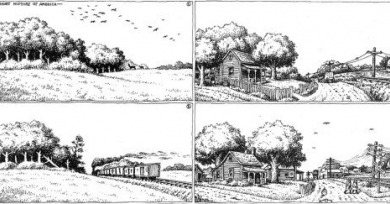

As the story of America unfolds, the emblems of civilization—cars, buildings, and above all those black, foreboding power lines—multiply like bacteria, until they are the story. Conceived, in theory, to make life more pleasant, contemporary American society has become a prison...

To view Coppola’s plots as flimsy or nonexistent is to miss the point. The depth of her work is not characterized by meaning, but by organization. The character portraits, spaces, and sounds that comprise her films foster a unified vision of emptiness.

Colonel Blimp contains one of the wittiest and most inventive sequences ever devised to show time passing.

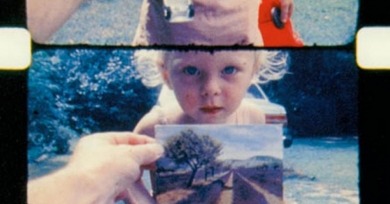

Family Portrait Sittings appeared not long after the emergence of the Boston-centric movement of personal documentary in the late 1960s, a wave distinct from the efforts of earlier avant-garde filmmakers to make a personal cinema, such as Maya Deren, Stan Brakhage and Jonas Mekas.

How soon after our heroine has been so viciously dispatched, turning our experience and emotions upside down, do we find ourselves itching for her body to disappear, even though this means her murderer will most likely escape justice? Just nine and a half minutes. Are we monsters?

Made up of a series of mostly short scenes that combine into a slow bubbling up of existential terror, the film does build to an extended, if narratively abstract, climax, which is then summarily followed by a denouement that manages to conclude the story in a most willfully unsatisfying fashion, while being almost subliminal.

The film focuses on the disruption of linear space and time created by psychic phenomena, allowing Roeg to masterfully explore the possibilities of creating, through camerawork and editing, a thoroughly nonlinear temporality even while depicting a succession of events.

Cinema is always about duration, from the quickest cut to the longest, most open-ended camera rove. How much a filmmaker can contain in one passage is the essence of the medium, regardless of matters of length.