Andrew Chan

Its unhurried pace and loose structure make it easy to mistake for a tribute to a life well lived, a leisurely exercise in smelling the roses.

Garland’s public life, in its tawdry overexposure, sheds light on the places where her character has been granted relative privacy and mystery.

If the critical community’s collective prejudice against the “message movie” becomes rigid dogma, then it will miss out on works such as those by pioneering Hong Kong filmmaker Patrick Lung Kong.

The film relies not on a formula of revelation by way of confrontation, but on its own trust in old-fashioned eternal truths. How does a film that makes such an ideal out of constancy drum up enough conflict and ambiguity to be compelling?

For every predictable move the script makes, the film grows richer and deeper by frustrating our expectations of what a big Hollywood epic is supposed to do in justifying its hero’s significance.

As if A Brighter Summer Day’s four-hour length weren’t intimidating enough to the uninitiated viewer, Yang makes sure to weigh his film down from the get-go, both formally and thematically.

For viewers on the mainland, City of Life and Death is an unprecedented opportunity to see one of the most devastating episodes in the nation’s history elevated through a universalizing, readily exportable cinematic language.

Rodrigues ultimately transcends his film’s shortcomings by taking a sincere approach to classic queer questions of aesthetic sensibility, community, and spirituality.

As someone who grew up with an awareness of being at the margins of a larger diaspora, I found the concept of an all-embracing Chinese-language cinema that could reflect the complexity and variety of life in overseas communities to be a major discovery.

Watching Mao’s Last Dancer, Bruce Beresford’s adaptation of Chinese-Australian ballet star Li Cunxin’s memoir, you might find yourself forgetting that ballet is an art.

Like many of the finest Spike Lee joints, the 1991 film is inconceivable without its carefully crafted soundtrack, and the music smooths out and opens up new ways of entering into Lee’s dynamic, purposefully choppy structure.

Sitting in the darkness of the theater, watching others experiencing the performance at some previous time, the concert-film viewer is always stuck on the outside, unsure whether to clap, stomp, or sing along or just watch reverently.

As Ghost Town drifts through its three loosely organized chapters, each populated by lonely and disaffected people just trying to scrape by, we gradually come to understand their skepticism.

Yi Yi’s exquisitely balanced and inclusive portrait of middle-class Taipei seems designed to accompany its devotees like a talisman through the years, and to continually renew and complicate the feelings we invest in it.

The almost mathematical control and precision of Firth’s lachrymal glands points to what proves to be most problematic about A Single Man.

As on Oprah, the lesson is ready to be had: we reap the inspiration of Precious’s empowerment without going through the fire.

Repeated viewings of Paradise reveal a transfixing and richly patterned patchwork, but on the first try it feels like alien territory, and it can be difficult to find one’s way in.

For a film that tries so mightily to appear intoxicated by art’s capacity for beholding and creating beauty, Bright Star just isn’t inquisitive enough about how such beauty takes shape in the gap between reader and writer.

On one level Beau travail is homoerotic because of the fetishistic gaze of its heterosexual female auteur, whose presence is all the more acutely felt for its interference in an all-male lineage of preceding authors.

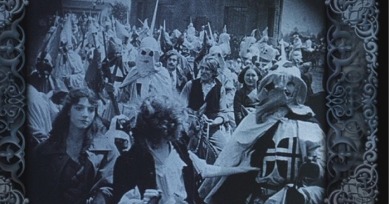

What extraordinary journey have we taken from these blackface caricatures we’re seeing on the screen to this black man on the stage freely expressing himself to a crowd of college students?