Smoke and Mirrors

by Andrew Chan

A Single Man

Dir. Tom Ford, U.S./UK, The Weinstein Company

Sometimes in movies a heartbroken love story can come together with one exquisite detail: a woman’s hand slowly being loosened from a lacey glove in Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence; a head resting on a shoulder in In the Mood for Love. Any film that hopes to map the sinuous contours of a past romance can be helped along by one of these smoldering moments, in which love is a delicate rare bird and reality splits off into an instant memory of itself. In Tom Ford’s A Single Man—which, like my previous examples, is a painstakingly aestheticized period piece that situates eros within a persistent longing for lost time—this scene arrives early. George (Colin Firth), a middle-aged British expatriate teaching at a small Southern Californian college in the 1960s, receives a phone call in his living room on a leisurely night alone. It becomes clear that the call is about Jim (Matthew Goode), his lover of sixteen years who, in the film’s opening dream sequence, is seen lying dead in a snowy landscape after a car crash. George’s response to the bad news is disarmingly elegant: while clearly flustered, he also maintains the steadiness of his voice so as not to impose his distress on the deliverer of the message. We grow curious to see how much pain will crack through Firth’s stereotypical poker-faced Englishness. Then, as if on cue, a sliver of water moistens the bottom of each eye. Only when the phone has returned to its cradle do two perfectly round tears come traveling down George’s otherwise minimally expressive face.

If there has been a more beautiful piece of Oscar-hungry melodramatic acting this year, or a more welcome expansion of a movie star’s previously constricted persona, I haven’t seen it. And yet the almost mathematical control and precision of Firth’s lachrymal glands points to what proves to be most problematic about A Single Man, particularly when considering it alongside the poignant but harder edged 1964 Christopher Isherwood novel on which it is based. In Ford’s interpretation, the protagonist is a bookish, hermetic neat freak whose experience of loss has driven him even deeper into his shell. While the book grants him a few flickers of catharsis, Ford keeps George hemmed in, and then proceeds to use the character’s micromanagement of himself as a guideline for composing every shot. There is hardly an image that goes by that doesn’t feel strained and sweated over—from the opening underwater ballet of naked male bodies to the languorous tracking shots through George’s family-friendly neighborhood—and we are forced to search for a pulse in this airbrushed vision of grief and loneliness. Certainly there can be something exhilarating about seeing a filmmaker obsessively tending to each onscreen detail and its corresponding emotion, but this requires a master like Wong Kar-wai, whose meticulous approach seems both effortless and irrepressibly passionate. Ford tries to access the swooning, regretful romanticism that’s become Wong’s specialty, most obviously through his collaboration with 2046 composer Shigeru Umebayashi. But neither Ford’s studiousness nor his overall competence can disguise his inability to distinguish an emotion that is genuinely felt from one foisted upon us through showy surface effects.

To get a sense of just how literal-minded Ford is about the relationship between images and feelings, one need only witness the way he and cinematographer Eduard Grau establish George’s downbeat mood through a palette of steel blues and grays, then vary it (at moments when a sentimental image breaks through George’s numbness) by saturating the colors so that every flower becomes blindingly bright and every character rosy-cheeked. In truth, how one responds to this undergrad-film-school artiness may depend on how one takes to Ford’s rock-star persona, which was largely cultivated in the Nineties during his stints as Gucci and Yves Saint-Laurent’s creative director. Whether unfairly or not, it’s virtually impossible to separate A Single Man’s emotional deficiency from the double-edged role Ford has played as a symbol of gay power. On the one hand, Ford embodies the ideals of ambition, talent, and impossibly sleek style by which mainstream America has elevated the gay male to the status of cultural arbiter. On the other, his attempts to brand himself through vapidly provocative photo shoots and ad campaigns (often featuring him posing alongside nude male and female models) helped to further link the public face of gay culture with a stereotype of martini-sipping, sunglass-wearing narcissism and self-commodification. Ford spoke in a recent New York Times article of his dismay at being seen as nothing more than “a beautiful black lacquered box with a platinum handle.” One can imagine that such views will only be increased by A Single Man.

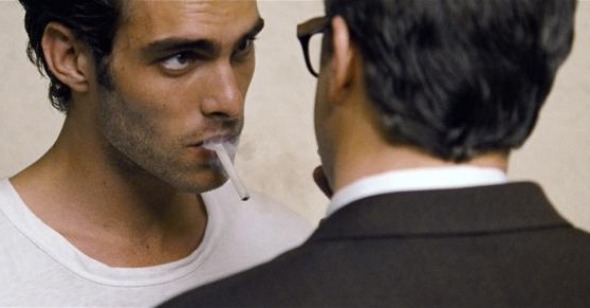

Surely a story about love, death, and aging would seem to offer Ford the perfect vehicle for proving there’s a soul behind his vanity. Isherwood’s novel has built-in cachet as a pre-Stonewall classic, but the narrative is lean enough for a filmmaker to find his own individual path into the material. For the most part Ford succeeds in establishing the right rhythm and pacing. Hollowed out by his sense of loss, George drifts through life as if in a state of reverie, and despite the film’s reliance on banal symbolism to evoke his frame of mind, there are also moments that are surprisingly sensitive to the emotional indeterminacy of grief—that inability to grab hold of one coherent feeling through the haziness of one’s sensations. But many of Ford’s interpretations and embellishments of the text ring false, and at times reek of the safe, drab legitimacy of the queer prestige picture. As George goes through the motions of his day (the film takes place over one 24-hour period), he encounters two young men who serve as potential objects of desire—one of whom is a student (Ken doll lookalike Nicholas Hoult) who follows George around campus and chats him up on the meaning of life, and the other a Spanish hustler who propositions George outside a convenience store. Casting actors who may as well have stepped out of a Calvin Klein ad, Ford seems to imagine L.A. in the Sixties as some golden age of pretty boys, but where Isherwood imbued his protagonist with the complexities of a painfully self-aware “dirty old man,” Firth’s George is rendered sympathetic through his chasteness. Even more damaging is Ford’s decision to reorganize George’s day around a suicide plot not found in the book—a morbidly sentimental device that seems to have been lifted directly from The Hours, and is contrived to grant George a warm-and-fuzzy spiritual transcendence that Isherwood would have rolled his eyes at.

If A Single Man is ultimately undone by its unwillingness to complicate the clichés of both gay and anti-suburban narratives (some of which are the very things that date Isherwood’s otherwise remarkable book), it also manages to provide one passage that vividly humanizes an enduring queer archetype. As George’s only friend, fellow British expat Charlotte, Julianne Moore stands in sharp contrast to the low-key male characters by wearing her neuroses on her sleeve. We watch her carefully applying make-up, getting her face together for her weekly date with George, hair piled high in a frenzy of tendrils. Living alone after being abandoned by both her lover and her son, she clings to George, demanding an intense emotional connection with him that he is too weary to provide. When they finally get together for dinner midway through the film, it becomes clear that she’s in love with him, and a sequence that begins with Moore’s trademark hysterical laughter and an interlude of carefree dancing rapidly descends into a display of the pair’s long-suppressed tensions. Has there ever been a cinematic representation of gay male-straight female friendship this unsettling, this gut-wrenching? To a degree, Ford recycles the misogynistic tendencies of the novel in his characterization of this bitter, vampiric fag hag. But in the interplay between icy Firth and fiery Moore, something new emerges—a brief, unexpected submission to emotional chaos that becomes the film’s sole improvement on its source. The drama of this scene derives from understanding how fiercely these two adults want to believe they are immune from their pain and self-absorption, and from observing how the habits of friendship can be both comforting and crippling. If Ford had represented George’s love life with the same amount of ambiguity, A Single Man might have been one of those rare creatures: a great gay weepie. As it stands, the film is most memorable as a nightmarish take on Will & Grace.