Death by Numbers

By Andrew Chan

City of Life and Death

Dir. Lu Chuan, China, Kino International

More than anything else in cinema, films about twentieth-century atrocity heighten our awareness of what’s ethically at stake in the representation and dramatization of suffering. Writers across a wide range of disciplines continue to discuss how such subject matter has held visual media—and indeed our entire image-saturated culture—in a moral and epistemological crisis. At times this strain of philosophizing has proven tiresome, particularly in the obvious ways it yokes a discourse of melodramatic extremes (with adjectives like “unfathomable” providing the routine description of the Holocaust) to film theory’s ever-shifting, ideologically charged attitudes toward realism. Still, the topic has the power to organize artists and critics along partisan lines, pitting self-conscious avant-garde practices against seamless traditional narrative, Godard against Spielberg. It’s no surprise then that Lu Chuan’s City of Life and Death has found itself embroiled in a controversy of increasingly global proportions. This big-budget epic about the Nanjing massacre has received a mixed reception not only in China, where its ambiguous political sympathies have periodically been attacked as unpatriotic, but also in the world of international cinephilia, where the atrocity film maintains its schizoid status as a prestige item, a bad object, and a testing ground for the capacities and inadequacies of art.

For viewers on the mainland, City of Life and Death is an unprecedented opportunity to see one of the most devastating episodes in the nation’s history elevated through a universalizing, readily exportable cinematic language. Much of the film’s urgency stems from its conviction, implicit in its aesthetics, that the massacre is worthy of being translated in slick Hollywood terms, and that it should be canonized as one of cinema’s great historical subjects. The process of memorializing those horrific few weeks in 1937 when over 300,000 Chinese civilians and soldiers were exterminated has been an arduous one, since the most conservative Japanese continue to deny that it ever happened, and the PRC government has repeatedly manipulated the facts to its own political advantage. Previous Chinese and Hong Kong¬–produced films on the subject have been uniformly crass, though audiences have rallied around glorified exploitation flicks like T.F. Mou’s Black Sun: The Nanking Massacre and Wu Ziniu’s Don’t Cry, Nanking (both from 1995), because they at least mirrored the intense feelings the massacre continues to provoke. Since the event only reached widespread international recognition in 1997, when American journalist Iris Chang published her book The Rape of Nanking, this high-class silver-screen treatment seems like one more significant step in granting the mass killings truth and legitimacy, the appearance of a commonly shared knowledge. If the major task of cinematically commemorating a past trauma is to earn it admission into popular consciousness, then Lu’s may be the first truly successful Chinese film of its kind.

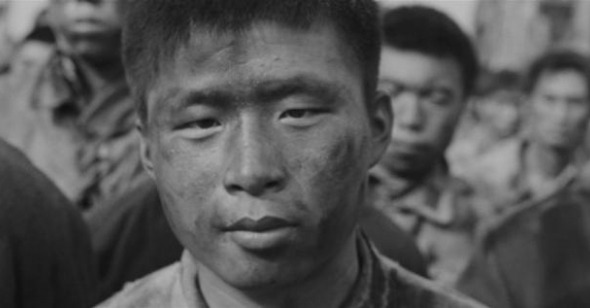

An aesthetically ambitious blockbuster, City of Life and Death forces us to again wrestle with some of the arguments usually provoked by Holocaust films within the context of a lesser-known tragedy. The first question Lu’s film raises is one of beauty: what role should it have in a film that depicts ultimate pain and cruelty, and in what proportions should it exist alongside evil’s banality? Audiences will be hard pressed to find a more gorgeously composed or seductively lit piece of black-and-white cinematography in recent cinema. Out-poeticizing Janusz Kaminski’s work on Schindler’s List (which serves as his most obvious model), DP Cao Yu packages each extended sequence of brutality with a handful of unforgettable images. Before the film launches into its nearly wordless opening battle between the Imperial Japanese Army and a weak, outnumbered band of Nationalist Chinese soldiers, three balloons float out from behind a veil of mist, the banners attached to them proclaiming that the Japanese have completely surrounded Nanjing. In the next shot, the sheepish, sympathetic soldier Kadokawa (Nakaizumi Hideo) opens his eyes, looking up at these harbingers of war as if they were imagined cloud formations.

Spielberg may have chosen black-and-white for the look of sober, official history, but Lu and Cao’s Schindler-inspired visuals create unexpected tension as they alternate between terrifying lucidity and a dreamlike haze. The crisp, clean lines of one shot dissolve into soft focus (or sometimes a plume of gray smoke) in the next, highlighting the conflict between barely individuated figures and the volatile background consuming them. In this visual scheme a small detail, like a dead horse lying in a city square, is reminiscent of something as sublimely allegorical as Werckmeister Harmonies, in which an apocalyptic setting contains glimmers of the supernatural. Though Lu’s film is filled with these elegantly orchestrated reveries, it is constructed as a series of self-enclosed set pieces. As it becomes more and more difficult to ignore how exquisitely made the film is, and what a leap forward it represents for Lu’s style, the problem of beauty opens onto other issues. One of the most crucial: how to account for all those writhing, tormented human bodies onscreen as the director juggles his gauzy lyricism and precisely calculated narrative effects?

The opening battle is followed by extended passages that specifically address the rape and murder of Chinese women, the moral compromises of virtuous Nazi John Rabe (who managed the city’s one Safety Zone) and his translator, and the tenuous opportunities for rescue and escape. One would imagine that the long list of crimes committed in Nanjing would lead a film down an inevitable path of anarchy and disorder, but what we find in City of Life and Death is a director with an unnerving amount of confidence, one who is in complete control of his environment. Taking his cues from propaganda films, Lu has mastered the art of envisioning masses in solidarity against a common enemy. A band of Chinese soldiers brings the film’s opening chapter to its climax by shouting “Long live China!” and “China will not fear!” in unison as they face certain death, heroic music swelling. In another gut-wrenching scene, a crowd of women who have found shelter in a church are asked to volunteer as sex slaves for the Japanese soldiers in exchange for food and heat during the winter. One defiantly attractive woman after another offers herself up for this ultimate sacrifice, and Lu frames each solitary hand as it’s raised, surrounded by a saintly glow and dust particles drifting delicately through the air.

The synecdochic use of the human hand recurs at crucial moments, signaling, variously, courage, desperation, and acquiescence. Since Lu generally approaches the body with the kind of disregard implicit in this wartorn landscape, the limp, raised, and outstretched hands provide a much-needed element of corporeality. At the same time, a viewer can’t help feeling that Lu has slipped right into the trap that made Gillo Pontecorvo’s Kapò an object of contempt in Jacques Rivette’s seminal 1961 essay “On Abjection.” In the now-infamous scene in which Emmanuelle Riva throws herself against a concentration camp’s electric barbed-wire fence, Rivette finds unconscionable Pontecorvo’s aestheticization of death—the way the camera “tilt[s] up at the body, while taking care to precisely note the hand raised in the angle of its final framing.” This image, which has long been synonymous with the pitfalls of beauty in atrocity-themed films, is echoed in the brief but remarkably distasteful final moments of City’s comfort-women segment. Here we are invited, through the horrified eyes of Kadokawa, to stare at the porcelain skin of a dead rape victim—first at her legs, her still-beautiful face and the tiny smudge of blood at her mouth, then finally at her inert hand as she is thrown into a wheelbarrow with other female corpses.

This offense is deepened by Lu’s lazy approach to characterization. While his reluctance to give voice to fully formed, believable personae may have its ethical advantages—preventing easy identification, for instance, or minimizing our ability to take comfort in forceful displays of agency—it also finds the director falling back on some painfully obvious methods to elicit our sympathy. As in his debut The Missing Gun, which thrived off the natural charisma of its lead Jiang Wen, City of Life and Death tries to create empathy through the use of Chinese movie stars such as Liu Ye and Gao Yuanyuan. At times this device feels reminiscent of Schindler’s List’s red-tinted girl, an attempt to assign us tour guides through a sea of undifferentiated suffering and to reaffirm our belief in the value of the individual. More disturbing is Lu’s manipulation of women and children as catch-all symbols—mostly of virtuousness and defenselessness, but also (at the film’s tentatively hopeful ending) of transcendence and resilience. The sentimentalization of female victimhood is at the root of Kadokawa’s status as a sympathetic figure—a characterization that has incensed Chinese audiences bred on one-dimensional, mustachioed Japanese villains. Kadokawa’s youth and innocence are established not so much through his horror at killing civilians, but through his premature ejaculation in the presence of a prostitute who becomes the object of his matrimonial fantasies.

While the body count of the Nanjing massacre is obviously dwarfed by that of Hitler’s genocide and the extensive machinery that enabled it, scholars and artists have long used the Shoah as a benchmark by which to reformulate Nanjing’s place in the history of atrocity. In arguing the scope of the violence, Iris Chang notes that while “Hitler killed about six million Jews… these deaths were brought about over some few years. In the Rape of Nanking the killing was concentrated within a few weeks.” The desire to force this massacre into visibility is understandable—like all of the great evils perpetrated in the twentieth century, it has long been absent from textbooks and threatened with complete erasure from our historical memory. But in competing for public attention, it has often resorted to mimicking the image of the Holocaust, and Lu’s film seems to be the apotheosis of that effort: a sturdy, memorable epic that makes an icon of the event, and also conforms to a level of production value and surface tactfulness that Black Sun and Don’t Cry, Nanking lacked.

The failure of City of Life and Death must make us ask: Must a film that depicts mass slaughter somehow disfigure traditional forms, so as to impart to audiences the difficulty (or even the impossibility) of narrativizing, containing, and making palatable what should morally be unimaginable? Must this film follow the example of Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah and focus solely on the inability of the present to reveal traces of the past, and the callousness of an Earth that could survive human atrocity unscathed? Must this film engage with the fact that so much of the evidence of the killings has been destroyed, and emphasize the essentially imagined nature of reenactment? Creating the images by which we remember atrocity is one of the riskiest tasks a filmmaker could ever take on. Nevertheless, the strict moral imperatives that have long condemned certain kinds of representation have begun to loosen, as the notion of “unrepresentability” has become a formal cliché and moral cop-out. What strikes me as troubling about City of Life and Death is not that someone dared to make a big-budget blockbuster with an easily comprehensible linear narrative out of this tragic historical episode. Rather, it’s that Lu never intimates that this comprehensibility might itself be terrifying. By the end it’s hard not to suspect, as Rivette did of Pontecorvo, that Lu has neglected to consider any of these most fundamental questions.