The Cadenza

Julien Allen on Psycho

The greatest filmmakers, like the greatest novelists and poets, are trying to create a sense of communion with the viewer. They’re not trying to seduce them or overtake them, but, I think, to engage with them on as intimate a level as possible. —Martin Scorsese, The Times Literary Supplement, May, 31, 2017

Beneath the cloak of simplicity Alfred Hitchcock wore when publicly describing his relationship with his audience lay an immeasurable—and constantly evolving—complexity. By the end of the 1950s, after the director had spent 20 years in Hollywood, paying viewers knew what to expect from a Hitchcock film: to be thrilled, scared, occasionally horrified and finally—with one or two exceptions—delivered from all their delicious discomfort by a neat, if not always happy, conclusion. The combination of excited anticipation and the joyous certainty of comfortable resolution meant that the punctuation of gasps by nervous laughter was a widely reported phenomenon in test screenings of the time, even if laughter during Hitchcock screenings today is now a subject of cinephile debate, evoking respect for one’s fellow audience members and the great man’s supposedly solemn authorial intentions. Laughter can be an instinctive defense mechanism against fear, especially at flamboyant climactic moments: Johnny Aysgarth’s grimace at the end of Suspicion when you can’t tell whether he's pushing his wife out of the car or trying to rescue her (Cary Grant at his most frenzied and bizarre); or Lars Thorwald looking straight at the audience from across the courtyard in Rear Window (a moment, thanks to its immaculate construction, surely as awe-inducing as anything in Hitchcock’s work). However grim the subtext, a convivial, contractual predictability inhabited all of Hitchcock’s Hollywood films, counterbalanced by a necessity for plot-based unpredictability (Hitchcock’s side of the bargain—to disarm us). But beyond that? When Hitchcock openly admitted to Truffaut that he was “playing the audience like a violin,” he was using a huckster showman’s language, or more particularly in his case, an illusionist’s. And one of the keys to an illusionist’s art—even one who self-promotes as wildly as Hitchcock did—is never to tell the whole truth about what you’re really doing. Some of the more celebrated magicians of today will even go so far as to pretend to divulge the trick’s method; but if they ever do this, you can bet your last dollar they won’t be telling you everything.

With the release of Psycho in 1960, Hitchcock played his greatest and dirtiest trick. He made a horror film that was more manipulative, more genuinely horrible, and more unpredictable than any before, but he also accentuated in a quite intimate and sinister way something he had always been fascinated by: the role of the audience in the cinematic process. Beyond simply reassuring them that they were being played—which was what they wanted—with Psycho he would make them into knowing accomplices to the characters’ behaviors, both during and after the fact, calling to mind Thomas de Quincey’s aphorism in Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts: “He who observes, spills no less blood than he who inflicts the blow.” The subjective camera in Psycho is not that of the villain (despite Robin Wood’s thesis that we “become” Norman, there are no pure point-of-view shots) but that of the audience itself, egged on and guided by the director, watching a little too closely and a little too eagerly what the villain is doing.

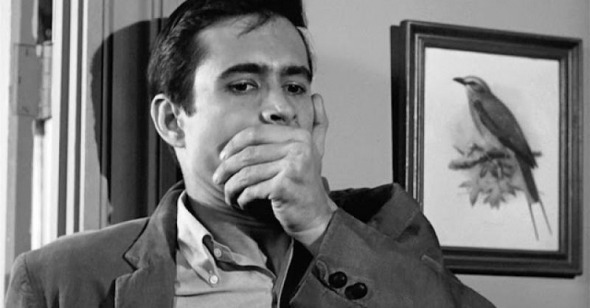

This loss of innocence on the part of audiences (what David Thomson called a “loss of virginity”) is rammed home by some of Hitchcock’s most demonstrative and memorable set-pieces. The murders of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) and Arbogast (Martin Balsam) and the discovery of Mrs Bates’s corpse in the cellar—the latter interrupted by her son’s grotesque drag entrance—all brought to the Hitchcock formula an unprecedently overt nastiness. (Vertigo, for reasons we will touch on, is a far less pleasant film, wrapped in a far nicer one). But perhaps the most compelling display of Hitchcock’s bravura in Psycho occurs during one of its least discussed sequences, in which Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) cleans up the crime scene, immediately after he discovers Marion’s body. Its duration alone—nearly ten percent of the film—is prima facie remarkable, and it contains, in its nine and a half minutes, an encyclopedic collection of escalating and conflicting sympathies and emotions, as well as directorial deceptions which are all the more exceptional for the director’s justified confidence that they would be almost invisible on first viewing. Between the murder itself and the cleanup sequence, Hitchcock delivers fully 16 minutes of what is effectively silent cinema, cut into two bluntly different sections: the first (the murder) is bright white, frenetic, and graphic; the second (the cleanup) is dark grey, inconspicuous, and cunning.

The most obvious observation to make about the cleanup scene’s duration is that the audience might have required a substantial period of “cooling down” time, merely to come to terms with what they had just witnessed. Marion’s murder—commonly, “the shower scene”—has a historic visceral power, derived as much from its brutally sadistic cruelty as from its narrative upheaval, sexual frankness, and technical virtuosity. Over the years, it has been discussed, deconstructed, and decorticated almost as meticulously as it was first storyboarded by Hitchcock and Saul Bass prior to shooting. A recent documentary feature, 78/52, consecrates 90 minutes of expert analysis to this scene alone. One test audience member at the time of Psycho’s release testified thus: “...we were really in shock from that, I mean, there was absolute silence in the rest of the film, people were in total mourning for the loss...”

How to follow this? In the absence of comic relief, which even for Hitchcock, pre-Frenzy, would have been too much, we are offered instead a sequence of apparently extreme banality: Norman mopping, rinsing, tidying up, lifting and clearing—disposing of the evidence of his mother’s terrible act. Until Jeanne Dielman 15 years later, this was possibly the longest housework sequence in the movies. So, just what are we watching? Are we even paying proper attention during this scene? Are we conscious of its duration? Here’s what happens immediately after the camera pans away from the gruesome spectacle of Marion’s death, toward the window of her cabin, through which the Bates house can be seen:

Norman, from inside the house, exclaims: “Mother? Oh, God, Mother! Blood. Blood!” and runs down to the motel, discovers Marion’s body and recoils in disgust. He closes the window, sits on the bed and thinks. He closes the cabin door and switches off the light, exits the motel room, proceeding to the office to switch off the motel’s neon sign. He reappears in the moonlight with a mop and bucket, re-enters the bathroom, turns off the shower, retrieves the shower curtain from under Marion’s body, lays it out on the bedroom floor and drags the body onto it. He rinses the blood off his hands, then uses the mop and a towel to wipe the blood off the bathtub, floor and walls. Leaving the cabin, he proceeds to the driving seat of Marion’s car and repositions the car closer to the cabin, popping the trunk. He wraps the curtain around the body and carries it out to the trunk. Returning to the room, he gathers Marion’s room key and effects and stuffs them into her case, then tucks the case in the trunk with the body, along with a rolled-up newspaper he sees on the bedside table. He drives the car a short distance and pushes it into a swamp. He watches the car sink.

Anyone familiar with Psycho (certainly anyone who has seen it more than twice) will immediately have identified one or two highly subjective elisions from the summary above, which we will come to. Firstly though, on the question of audience respite, it’s notable that Hitchcock decides to stay at the location of the crime. If he’d wanted a strong cutaway to release the viewer from the trauma of the shower scene, he could have transposed the action far away from the Bates Motel to those characters who have a concern for Marion’s disappearance—her boyfriend in the fictional Californian town of Fairvale (John Gavin) or her boss back in Phoenix (George Lowery) who had entrusted her to deposit the money she decided instead to steal. The scene is not really about emotional respite, but about taking advantage of the audience at their most vulnerable and pretending to provide them with emotional respite, while actually pursuing something else. So, despite the change of tone, rhythm, and color, the viewer is not completely absolved from the urgency of what went before. Instead, Hitchcock immediately shifts the burden of peril onto the film’s new protagonist, Norman Bates.

Norman, after all, is at this point a conspicuously sympathetic character: clearly a victim of an overprotective mother, a kindhearted, gentle (if disturbed) soul whose homespun wisdom and simple decency had—unbeknownst to him—already persuaded Marion to return to Phoenix with the stolen cash, before Mrs. Bates ruined everything. Imprisoned in the motel, Norman has long been forbidden a normal sex life by his corrosively puritanical mother. In the circumstances, can you even blame him for his only evident shortcoming (that he’s a peeping tom)? Despite being puzzled and slightly saddened, at no point does Marion feel remotely threatened by Norman. Certainly, if we contrast him with the protagonist-voyeurs portrayed by James Stewart in both Rear Window (“JB,” an impossible braggart, a safari macho so blindly self-absorbed he won’t lift a finger of compromise to meet a devoted Grace Kelly halfway) and Vertigo (“Scottie,” a startlingly insensitive and manipulative arsehole with necrophiliac tendencies), we’re on the flipside of the Hitchcock world, where a much more sympathetic character than the average Hitchcock hero will eventually turn out to be the villain.

Now the shower scene has alerted the viewer in the most abrupt way that this story is no longer going to be told from Marion’s point of view, so the cleanup scene serves primarily to transfer the audience’s sympathy from Marion to Norman, as swiftly and efficiently as possible. Whereas before we saw Norman through Marion, for the first time we see him directly for ourselves, so the scene serves as something of an introduction. As far as we can tell, Norman reacts much as we would react. He discovered blood on his mother’s clothing as she returned to the house and he was rightly horrified. Despite everything he must have endured at her hand, he still loves his mother and snaps into action to do anything to protect her by concealing the crime. As messed up a view of family mores as this might feel, it still makes Norman a protagonist in a predicament: someone worth rooting for. This transfer of audience affinity from Marion to Norman is crystallized by two separate moments of suspense, our reaction to which proves (if we can permit ourselves to assume that we all have the same reaction) that we want the same thing that Norman does: as he emerges from the cabin with the mop and bucket, he is fixed in a car’s headlights, but it’s a false alarm and the car in question passes by; then at the end of the sequence, as he watches Marion’s car submerge itself into the swamp, it stops…before resuming its descent. These moments fall within a familiar Hitchcockian suspense methodology, and we are invited to share Norman’s relief when the threat passes. So, while the cleanup sequence is remarkably long and drawn out, in terms of what it achieves in one specific sense, it is also surprisingly short. How soon after our heroine has been so viciously dispatched, turning our experience and emotions upside down, do we find ourselves itching for her body to disappear, even though this means her murderer will most likely escape justice? Just nine and a half minutes. Are we monsters?

Hitchcock spends most of the film answering that question for us in the affirmative, and in this sequence, he does so by dancing on the tightrope between sympathy and identification. In the measured, purposeful tempo of the cleanup scene, we have time for more complex thoughts to percolate. Perhaps, on reflection, Norman’s decision to cover up the crime is somewhat precipitous? His few seconds of reflection on the bed are more likely to have been “how” than “what,” suggesting a malfunctioning moral compass. Then, witness how Norman pauses in the bathroom doorway—he is framed from behind in silhouette against the bright, white wall of the previous scene, mop and bucket weighing his arms down against his sides; he can surely only be gazing for a little too long at Marion’s mutilated naked corpse. Of most tangible significance to the duration of the cleanup sequence is Hitchcock’s refusal to leave any aspect of the cleanup out. Each deliberate section of action, however outwardly unnecessary to advance the narrative, is kept intact (except for what appears to be a nondiegetic cut during the mopping of the bathroom floor). He wants us to see not only the trouble Norman goes to but also just how good he is at planning each step in the right order: almost as if he’d storyboarded the whole process in his head.

At no point is Norman really panicking, or he would have most probably dealt with the body first and mixed up the business with the car. Norman’s meticulousness is a ready audience identifier of his own potential psychosis and his time-and-motion skills are disconcerting. (“Just how many times has he done this?” we might ask ourselves.) In the final analysis, it feels like he’s in cahoots with his psychopathic mother and seems to be able to control his emotions sufficiently to cover up the crime with impeccable acumen. He isn’t even distracted by the rolled-up newspaper and what it might contain. And what does it say about the emotional priorities of those of us who react with frustration that he tosses all that cash into the trunk with Marion? As well as being a nihilistic commentary on the futility of life, this is also another psychological flashpoint—another conjurer’s misdirection?—for us to contend with.

So, what might initially have struck us as a desperate, touchingly loyal act has, progressively over the course of this nine-and-a-half-minute duration, started to become either consciously or subconsciously troubling. Bernard Herrmann’s score, in heavy contrast to the shrieking motifs of the preceding murder, is noncommittal: its portent-laden, rubato string passages, alternating between upper and lower registers (the score’s track list identifies “The Body”; “The Office”; “The Curtain”; “The Water”; “The Car”; “The Swamp”) denote foreboding, without being as condemnatory or revealing as the tracks which preceded the murder (“The Window”; “The Parlor”; “The Madhouse”; “The Peephole”), all of which feel alerting and judgmental in terms of our attitude to Norman himself. Before the murder, Hitchcock could afford to allow Herrmann to suggest all sorts of potential problems with Norman (while Marion was the protagonist), but he reins it right back at this crucial juncture, after the murder has happened, to let the audience—faced with a threat to Norman himself—reach their conclusions. With each new movement in the sequence our sympathy, which we are straining at the outset to give Norman just because we need somebody, is polluted by confusion and distrust. But significantly, it’s safe to assume our identification with him doesn’t waver. For the sake of the narrative we need him to succeed, or the police will inevitably find the evidence, and this story, and all its grisly promise, will end with a whimper. One detail at the scene’s conclusion impacts different audiences in different ways. Some may never notice it, others enjoy it but think nothing more of it, but for the rest it clinches the argument. In the half-light, Norman, with alarming complacency, pops a new stick of gum as the car sinks into the mire. When it stops sinking, he stops chewing. When it resumes its descent he relaxes, half-smiles and chews again. We’re rooting for the bad guy.

What first attracted Hitchcock to Psycho was, by his own admission a durational element: the “suddenness” of the first murder, which he was confident he could do something very special with. The temporal dynamics at play between the shower scene and its immediate aftermath are fascinating in themselves. In a sense, once Marion’s head hits the bathroom floor, the entire story stops dead. But like a cadenza in an orchestral concerto—perhaps a lone piano solo hovering over the dying embers of the main theme’s explosive closing cadence—another timeline (another story, that of Norman) overlaps, softly and tentatively. It creeps up and draws the audience in, slowly but purposefully, providing clues here and there for those who pay most attention: like a moment in time where the world of what we thought was Psycho—of the affair, the theft, the chase, the murder—seems to freeze and we’re left with just us and Norman, getting to know each other.

If we consider Hitchcock to be the grand master manipulator, at the fountainhead of the evergreen moral debate about how audiences should be treated (cf: Verhoeven, Tarantino, Haneke), what often gets lost in the argument is the extent to which this manipulation sometimes starts to resemble empathy, especially as it requires a deep-rooted technical understanding of audience emotion. Hitchcock loudly trumpeted his own cynicism to anyone who would listen, because he knew that masochistic audiences felt good about handing over control to him and that he could always deliver. But he also knew that for his films to work, they needed to construct a much more precarious emotional balance than if he had been operating outside the thriller/horror genre. Real trickery—in creative terms—is expensive, not cheap.

Psycho was widely “credited” with normalizing unbridled darkness and cruelty in mainstream cinema, at the same time as confronting its audience with its own desire to watch bad things on a Saturday night out. (Who among us can honestly say that when the camera condescends to show us just what Norman sees through that peephole of his, we avert our eyes?) Yet beneath its groundbreaking horror metrics and the gnawing discomfort of audience complicity, there endures in Psycho a peerless artistry that feeds off the very sensibilities it has assaulted, to heighten their responsiveness further. That’s Hitchcock: he lifts us to the firmament of cinematic experience, even while pushing us into the swamp.