Time Unrefined

Jackson Arn on Crumb

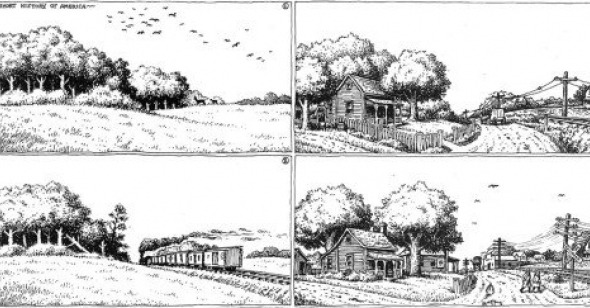

It begins, as plenty of sad stories do, in a calm, Edenic forest. Birds flutter by, deer graze. A moment later, all the animals have vanished. The forest is still there, but it’s much sparser. A train speeds by. Another blink, and the forest is almost gone. There’s a little house, no doubt made from the trees that once grew nearby. Power lines stretch away in the distance, connecting the modest community to countless others. Stop me if you see where this is going.

Time passes, and soon only one tree is left standing. Power lines run back and forth across the sky, mocking the forest that once grew here. There are plenty of cars but, curiously, few people. As more time goes by, we start to see ads for big, gross American companies. By the end of the story, the power lines and streetlights threaten to black out the sky, cars putter around meaninglessly, and a hideous “STOP ‘N’ SHOP” sign hangs like an epitaph over the whole, sorry scene.

The first thing you notice about “A Short History of America”—a comic strip by the great American cartoonist Robert Crumb, which appears, one panel at a time, toward the end of Crumb, Terry Zwigoff’s 1994 (anti)biographical documentary—is its awesome bleakness. As the story of America unfolds, the emblems of civilization—cars, buildings, and above all those black, foreboding power lines—multiply like bacteria, until they are the story. Conceived, in theory, to make life more pleasant, contemporary American society has become a prison, wiping out the natural world and enfeebling the people trapped inside.

But the second thing you notice about “Short History” is its concision, which stands in striking contrast to the bloated society it chronicles. Into twelve cartoon panels, presented over the course of just 51 seconds, Crumb and Zwigoff cram four centuries of history: the Transcontinental Railroad, the Great Depression, urbanization, and, if you look a little closer, gentrification, the rise of big business, and the privatization of transportation. Crumb is a master of simplification, whittling the story of America down to a few essential characteristics and motifs. Depicting such an enormous stretch of time in dramatically shortened, cartoon form allows him finds the lighter side of a story that if presented in its entirety would be too disgusting for some people to stomach. He’s not making American history any cheerier, but at least he lets us laugh at the sick joke of it all. In the tens of thousands of cartoons Crumb has drawn since the ‘50s, he’s given his own screwed-up life the same treatment.

“Bleak and concise” might as well be Robert Crumb’s motto. It’s also the reason why his art is both ethically challenging and hysterically funny. From his childhood sketches of murderous pirates to his more recent illustrations of the life of Franz Kafka, Crumb has offered the same vision of human misery, which he shows every sign of believing wholeheartedly. He was born in Philadelphia in 1943 to Charles, a military man turned corporate efficiency coach, and Beatrice, who spent more time popping amphetamines than raising her children. He started drawing cartoons because his older brother, Charlie, made him, supposedly in unconscious imitation of their father, whom Charlie calls an “overbearing old tyrant.” In the early ’60s, he moved to Cleveland and married his first wife, whom he later divorced. In 1967 he relocated to San Francisco, where he worked on the legendarily transgressive first issues of Zap Comix and dreamed up such counterculture icons as Fritz the Cat, Mr. Natural, Keep on Truckin’, and the cover art for Cheap Thrills.

Faced with seven-figure offers from Hollywood and Madison Avenue, the anxious young cartoonist became more reclusive. A full-fledged curmudgeon at the age of 30, he turned his back on the counterculture as well as The Man. He renounced marijuana and more or less all of contemporary music, and, along with Terry Zwigoff, another recent Bay Area transplant, started an aggressively old-fashioned bluegrass band called The Cheap Suit Serenaders. In the 1970s and ’80s, his work grew more stubbornly misogynistic and racist, even as the great art critic Robert Hughes championed his social satire and called him “the Bruegel of the second half of the twentieth century.” Then, in the early 1990s, he and his second wife, Aline, moved to the south of France. Unlike other American creative geniuses who have poked fun at their own country, he put his money where his mouth was.

Some great artists delight in reinventing themselves through their work, but Crumb took the opposite approach. His oeuvre is a perpetual reworking of the neuroses he developed early in life, in particular his distaste for modernity and his fear of other people, especially women. In a way, Crumb’s childhood is his life, and his career as a cartoonist is a lengthy footnote to it. In the 1970s, turning down offers to draw cover art for the Rolling Stones and host Saturday Night Live allowed him to pursue more autobiographical projects, almost always revolving around his adolescent and teen years. Early in Zwigoff’s documentary, he sketches his high school crushes and reminisces about their hairy legs and braces. “Where are they now?” he wonders out loud, and then answers his own question: “Most of ’em are fat, middle-aged housewives.” Here, as in many of his darkest cartoons, Crumb seems to understand that the joke’s on him: 30 years later, he’s still losing sleep over women who never knew him to begin with. While most people find ways of forgetting the worst parts of their teen years, Crumb is incapable of losing one sweaty, self-hating second.

If Robert Crumb hadn’t been a real person, Terry Zwigoff, one of the last true Freudians working in American movies, would have had to dream him up. There are times in Crumb when Zwigoff seems to be playing the part of psychiatrist, gathering evidence for the psychological traumas his patient endured as a child. He finds plenty. Crumb and his siblings slept in the same bed until they were teenagers. His older brother, Charlie, bossed him around. His mother didn’t love him. His father beat him.

The documentary’s structure, insofar as it has one, consists of a slow, vulture-like circling around these influences. More than an hour of the film elapses before we lay eyes on Crumb’s infamous mother, a doughy old woman who obviously still terrifies her children. (Earlier in the film, Zwigoff catches Crumb speaking to her on the phone in the same tone Norman Bates used when addressing his own mama.) As late as the 90-minute mark, we’re still uncovering fresh horrors from Crumb’s childhood. But instead of adding up to a definitive statement, Crumb’s traumas further distort our understanding of the artist, pointing toward more pain but no more illumination. The documentary ends with two intertitles reminding us how little we really know about these people: first, that Charlie Crumb committed suicide shortly after the film was completed; second, that Robert’s sisters declined to be interviewed for the film. Exactly what went on in the Crumb household in the ’50s is a secret that will follow the family to the grave, but it surely wasn’t pretty.

*****

Rewatching Crumb, it struck me that “A Short History of America” may be the key to understanding Zwigoff’s film, if not Crumb himself. Both the documentary and the comic strip are masterpieces of concision, and both are defined by what they leave unsaid—every moment gestures to some greater, unbearable catastrophe. The result is that neither work gives any real sense of having summed up its subject, contrary to what the title suggests. Instead, Crumb and “Short History” remind me of something the critic John Berger said about the artwork of Francis Bacon: “The worst has already happened.” For Crumb, “the worst” means time itself, both in the sense of America’s long, miserable history and of his own miserable early life. What, if anything, can be done with this time?

Biographers across all media have to find ways of fitting their subjects’ lives into a finite amount of space, whether it’s a 500-page book or a two-hour film. Zwigoff’s isn’t just the ordinary expository challenge of finding something compelling to say about Robert Crumb’s life in 120 minutes—Crumb is no ordinary subject, after all. The problem Zwigoff faces is ethical as well as practical: conveying some of the pain of his friend’s past without making him relive it or, even worse, creating the impression that Crumb is no more than the sum of his traumatic experiences. To this end, Zwigoff uses the same technique Crumb perfected in “Short History” —he simplifies the past without denying it altogether.

It’s often observed that when turn-of-the-century roots musicians played sad songs, they were actually freeing themselves from sadness—at least for a time. To make music out of pain is a way of purging, not wallowing, and the more melancholy the song, the more joyful is the act of performing it. It’s no coincidence that Crumb’s soundtrack is full of early 20th-century blues, jazz, and, ragtime: only a handful of films have conveyed these genres’ full meaning more effectively (I’d need another essay, however, to get into the tension between Robert Crumb’s disdain for contemporary black culture, apparent in his comics, and his love for early 20th century black music). In many ways, Zwigoff sees Crumb as the inheritor of the American roots tradition. Perhaps with this in mind, he scores Crumb’s “Short History” to little-known Scott Joplin tune “A Real Slow Drag,” the sort of thing The Cheap Suit Serenaders performed in San Francisco in the 1970s. It’s the same song we hear earlier in the film, when Crumb sits by the street and converts various passersby into great, vivid caricatures, and it’s the same music we hear at the end of the film, after Crumb and his wife, Aline, have left for France. With each listening, the song takes on a deeper meaning, until it almost seems like the music playing in Crumb’s own head as he records, refines, and temporarily transcends the pain of experience. His artwork depicts misery, but it’s far from miserable.

If catharsis is a central part of Crumb’s artistic process, it also guides the way Zwigoff uses film to deal with the agony of lost time. He portrays the past as a series of faint traces—faded photographs, home movies, nervous laughs hiding a lifetime of tragedy. In this way, Zwigoff offers audiences a chance to experience Crumb’s trauma as he experiences it himself, as a gnawing, subconscious fear that occupies his thoughts even when he’s talking about something else. Yet doing so also allows Zwigoff to show his friend overcoming this trauma. What’s true of comics and the blues goes for cinema: to rehearse the past is to move beyond it, to feel good about feeling bad, as Zwigoff and Crumb have done throughout their respective careers.

If cinema’s power lies in its ability to create an “image” of real time, it’s at least as much defined by its ability to cut and compress. In this respect, Zwigoff suggests that directors have a lot to learn from comics. Recreating Crumb’s “A Short History of America” on film, he seems to offer a humbler interpretation of time than, say, André Bazin’s, premised on the idea that time is sometimes too painful to endure. Crumb suggests that it’s the nature of time to remain just out of reach, a looming monster that can be ignored or outrun but never escaped for good. And to this monster, Crumb and Zwigoff offer the same deft response: turn it into art, chuckle at it, and, at least for a while, move on.