Daniel Witkin

The soccer highlight video has proliferated. Whether 90 seconds or 10-plus minutes, these little portraits of players are essential for fans who try to keep up with the game in all its inexhaustible intricacies . . . They also have an aesthetic of their own, with their own characteristic music, montage, and mise-en-scène.

The carpets, which often line the floors and walls of the sets, both framing and filling Parajanov’s consistently delightful tableaus, present a vision of the poet’s world as something thought up by human imagination and crafted by human hands.

The actors interpret their often dense monologues with an admirable naturalness and, perhaps more importantly, truly work to convey the act of listening. In many ways, the work of Puiu in guiding the actors through the genuinely demanding material is a more impressive achievement than the heightened realism of The Death of Mr. Lazarescu.

"To try to approach this question I shouldn’t necessarily be looking only at the media or the makers of it, but rather at the eyes that see that media."

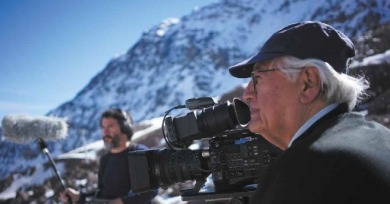

One can’t discuss Costa for long without focusing on his use of photography—it seems that with every successive film he learns something new about how digital cameras absorb light that no one else has yet figured out.

What is happening in Chile is related to what is going on in many other places. And I do see a parallel with the protests of the 60s. It seems the big circle of time is closing.

To process the layers of brutality and often half-hearted deceit that constitute much of contemporary public life in the former Soviet Union is no enviable task, but Loznitsa has taken it up with gusto.

As human beings, we still have components of our personalities that can be very primitive, but often we use the past as some kind of banner of authenticity. But why should something be more authentic just because it comes from the past?

Liu measures time through familial ritual, and her project is aligned with the work of Ozu and Akerman, tracking the process by which the passing hours accumulate into the passing of one generation into the next and onward into the flow of history.

Coming at a time dominated by talk of the bifurcation of the country, Monrovia, Indiana is an excavation of life in the other America. Its place within the career of Frederick Wiseman also works into this dichotomy . . .

The film thrives on translation, communication, and perception. Like the screwball comedies of yore, it revolves around a romantic conflict that its protagonist does not fully comprehend, though here this situation is reduced from the fanciful to the quotidian.

The first thing you should know is that Western is not really a western. Valeska Grisebach draws upon genre iconography and mythos, but to take the comparison further requires wishful, willful thinking, an act of projection that the filmmaker cannily encourages and exploits.

Cobbled together from home movies that the Brazilian director amassed throughout four decades living in Paris, the film constructs an autobiography of sorts from what its author happened to film over the years.

In Lubitsch’s movies, love simmers and strains, but it is equally likely to materialize within the space of a single gesture.

While the New York–set Hermia and Helena carries on the alternately fastidious and freewheeling sensibility of his previous Shakespeare films, it is the first to be set outside Argentina, as well as the only one thus far to engage with the Bard in English.

The implications of executive order Enhancing Security in the Interior of the United States recall the 1970 American independent film Ice, directed by Robert Kramer, dramatizing the resistance of a group of urban radicals in the face of an ascendant fascist government.

The setup of the film works less as narrative than as an inception point for numerous complementary and competing layers of fiction and reality, including the test footage for the film-within-a-film, scenes relating to its production, and footage of life in Tokyo.

This adaptation of Cosmos, the final novel by the great Polish modernist Witold Gombrowicz, directed by Andrzej Zulawski, is gorgeous, ceaselessly lively and funny, while also evincing a melancholic view of the human condition.

Through documentary and fiction, Patricio Guzmán and Jia Zhangke have explored particular ability of film to record history. Scrutinizing their respective nations—Chile and China—with unmistakable seriousness of purpose, each has earned a sort of authority regarding a particular moment in his country’s life.

Where Russian Ark deliberately decontextualized its various vignettes, Francofonia is generous almost to a fault with exposition, tracing the development of the German occupation in a leisurely manner.