No Escape

By Imogen Sara Smith

NYFF 2023:

The Dupes (Al-Makhdu’un)

Dir. Tewfik Saleh, Syria, 1972, Janus Films

For migrants and refugees, the earth becomes a cruel obstacle course in which they gamble with their lives. Tewfik Saleh’s The Dupes (Al-Makhdu’un, 1972) tells a searingly specific tale of displaced Palestinians trying to cross the desert to Kuwait, but it also inescapably echoes the stories we hear every day on the news: of migrants drowning in the Mediterranean, trekking across the Darién Gap, dying in the desert on the U.S.-Mexico border; and of the booming economy created by people’s desperation to reach a promised land. Based on the 1962 novel Men in the Sun, written by Palestinian author, activist, and militant Ghassan Kanafani while he was living undocumented in Lebanon, The Dupes was filmed in Syria with a mix of Syrian and Palestinian actors. Long a holy grail for the Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and the Cineteca di Bologna, it was finally restored in 2023 in collaboration with the National Film Organization and the family of Tewfik Saleh, and screens in the Revivals strand at the 61st New York Film Festival.

The opening image of a skull in the desert gives fair warning that the journey will be harrowing, but the film is also an explosion of cinematic inventiveness. It begins in a lyrical, impressionistic mode, slipping back and forth in time and shifting fluidly between subjective viewpoints. The three main characters are introduced with flurries of flashbacks that reveal why each of the men has decided to leave for oil-rich Kuwait and how he wound up in the Iraqi city of Basra seeking passage across the border. The style serves another purpose as well. The freedom with which the film jumps through time and space—through layers of the past, memories recalled out of order and scenes that repeat like a skipping record—sets up a stark contrast with the last part of the film, when the world of these men has shrunk down to an unbearably claustrophobic space, and they are trapped in a deadly countdown where every second matters.

With their vivid sensuality and poetic detail, the flashback sequences make us care intensely about these three men, ratcheting up the suspense once they throw in their lot with a driver who offers to smuggle across the border in his truck. First, we meet Abu Qays (Mohamed Kheir-Halouani), an aging peasant farmer with a wife and two young children. As he stops on his slog across the desert to rest in an oasis, the camera dances between the palm trees, giddily gazing up at the sun sifting through the fronds. He digs his hands into the moist earth, remembering another man’s words: “When I lie on the ground, I seem to smell my wife’s hair when she steps out of a cold bath.” His mind flits between idyllic pre-war memories of harvesting olives, a battle filling an olive grove with bullets and dust, and life in a refugee camp, evoked with a staccato montage of documentary photographs, as though time itself has stopped flowing for these homeless and stateless people.

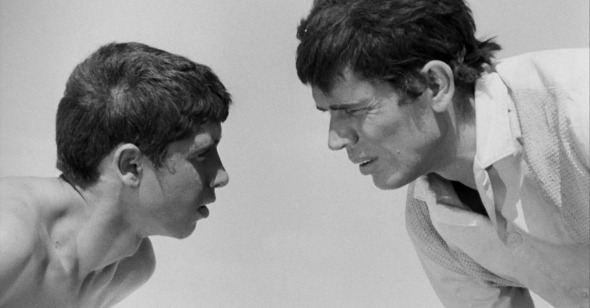

Abu Qays recalls a fellow villager who returned from Kuwait with tales of easy money, urging him to go and promising him that once there, “You’ll wipe away all the tears with banknotes.” Like him, the lanky, baby-faced schoolboy Marwan (Saleh Kholoki) is driven to emigrate by the need to support his family, since his mother and younger siblings have been abandoned by both his father and an older brother. As’ad (Bassan Lofti Abou-Ghazala), by contrast, is a charismatic political fugitive wanted for his militant activities in Jordan. The three men’s paths converge in Basra, where they each hesitate over the costly gamble of paying smugglers to guide them to the border. As’ad has already been abandoned in the desert by a previous guide, a trauma he keeps reliving. The desert is full of rats, says a stranger who picks him up on the road; when the man’s companion wonders what they eat, he quips, “Smaller rats.”

Should these migrants trust Abu Khayzaran (Abderrahman Alrahy), a truck driver who offers a quicker and cheaper route to Kuwait? With his wolfish smile, glib promises, and naked greed, he hardly inspires confidence. But Abu Khayzaran proves to be the most complex and morally ambiguous character in the movie. He too gets a back-story filled in by fragmentary flashbacks that erupt like nightmares. His obsessive lust for money springs from bitterness, exhaustion, and a gaping psychic wound. How guilty he is, and how guilty he feels, remain troubling questions.

Once the four men set out across the blank waste of the desert, The Dupes becomes a stripped-down, nerve-shredding ride. There is nothing but heat and dust; beating, blinding sun; wheels jolting over rocks; metal so hot that drops of sweat sizzle on it like a griddle. With pitiless hyperrealism and visceral physicality, the film brings us closer and closer to these men; as they fight to stay alive, the bare fact of their existence becomes everything. When the truck goes through border crossings, they must hide in the water tank, a grimy, abraded black box that looks like what it is—an instrument of torture. The scenes of them preparing to enter the furnace-hot tank, and coming out, are painfully extended and nearly wordless. The camera moves intimately over a tableau of their nearly naked bodies, so close you can all but taste their sweat and touch the vulnerability of their suffering flesh.

Saleh said that he intended the film to show the futility of these characters’ attempts to escape the humanitarian disaster of the Middle East in search of personal success or liberty, demonstrating that “there is no individual salvation from a collective tragedy.” The message is clear, and it’s conveyed with lucid fury. But it would not have the same devastating impact if the men were not individuals portrayed with tenderness that accentuates their harsh fates: if we hadn’t seen Marwan applying mud to the walls of his family’s hut with his hands, or Abu Qays joyfully tossing his baby into the air, into a freeze-frame that stamps the moment forever as an image of lost happiness.