Bare Necessities

Imogen Sara Smith on The Organizer

Robert Mitchum once said that one of the secrets of cinema acting is to “steal the reality of the props.” Unlike on stage, when movie actors are asked to build a fire, chop down a tree, dig a hole, fry an egg, or jump on a train, they are likely doing just that. By the way they handle real shovels, eggs, or matches, actors themselves can become real on screen: if “people believe you in the setting, they’ll believe whatever you say,” Mitchum concluded.

Some filmmakers, too, have understood how to steal the reality of the props. Among Mario Monicelli’s greatest gifts as a director was the expressiveness, specificity, and stubborn physicality of the worlds he creates. In his best-known film, the caper comedy Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958), he perfected a style that festoons the abraded, hardscrabble environment of neorealism with inspired sight gags, brilliantly deploying the deadpan silliness of certain objects.

This textured, tactile realism is even more potent in The Organizer (1963), Monicelli’s epic tragicomedy about the nascent labor movement in late 19th-century Turin. To watch the film is to inhabit the factory workers’ world: the scuffed, cracked surfaces in their homes; the rough, frayed fabrics they wear; the chilly, coal-scented fog they breathe and the muddy puddles of melting snow they trudge through; the fat, greasy sandwiches they carry wrapped in paper for their lunches. The period setting is so convincing that the credits shuffle together historical photographs with stills from the movie, and it is only a few recognizable actors who give the game away. For all the film’s sweep—the seething crowds, the urgent political debates—what remains most indelibly are passing details, often involving things: the broomstick that a young boy wields grumpily to break up the ice in a water pitcher when he rises to wash at 5:30 in the morning; the bulbous iron finial that a striking factory worker yanks out of a bedpost to arm himself when heading out for a showdown with scabs; or, most strikingly, the little wicker basket in which Professor Giuseppe Sinigaglia (Marcello Mastroianni), an itinerant labor organizer, carries his “necessities.”

The Professor inventories the contents of this basket after they’ve spilled out in the street: there is a darning egg, a bar of soap, a brush, a sock, and a piccolo. The darning egg, for some reason, sticks in my mind. Why should this tiny, seemingly insignificant object stand out in such a densely populated movie? It is perhaps partly the sheer oddness of the thing, and the way he cherishes it among his meager possessions. Much later in the film, we do see the Professor darning his socks—alone in the night, like Father McKenzie in “Eleanor Rigby.” This method of mending fills a hole or tear with new rows of stitches, using the wooden egg to keep the shape of the garment. But when he drops it into his second sock, it falls out through a gaping hole and rolls noisily across the floor—just at the moment when two policeman pound on the door, looking to arrest the agitator. As they pace around, one stumbles over the darning egg, but does not pick it up. Later, after the Professor has made his escape and taken refuge with Niobe (Annie Girardot), a prostitute who is the daughter of a factory worker, his friends contrive to bring him his belongings. We see the little wicker basket and the egg sitting on a table. By this point, it seems like a kind of totem for his character.

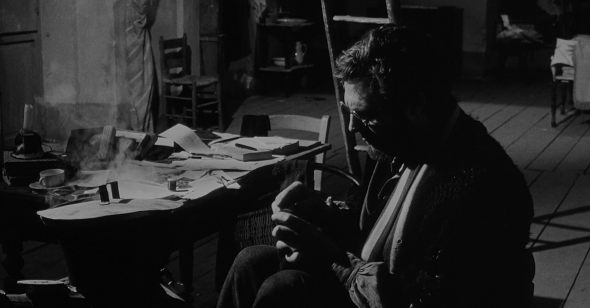

He is, to begin with, delightfully unheroic. Mastroianni obviously relishes upending his suave, glamorous persona to play this shabby, scuttling figure in a dusty hat, with a scruffy beard and round, wire-frame spectacles. He always seems to be hungry and cold: soaking his feet in a bucket of hot water, sleeping with a scarf tied turban-style around his head, gazing with almost cartoonish covetousness at other people’s food. In that scene where he darns his socks, expertly biting off the thread with his teeth, he wears a little crocheted shawl around his shoulders. While there is little doubt about his sexuality (he stands to attention very promptly when Niobe tells him that if he washes up he can share her bed), he eschews the machismo of other male characters, like Raoul (Renato Salvatori), the laborer reluctantly forced to share his apartment and his bed with the Professor while he counsels the strikers. In a marvelous scene of the two men in bed, Raoul accuses his guest of not caring about the workers, leading them into a fight they can’t win—and hogging the covers. Rather than argue back, Sinigaglia sighs plaintively, “You’re right, I’m not one of you. I have no family, no friends. No one is interested in me except the police.” The scene ends with Raoul gently tucking the blankets around his bedmate, and as the film goes on he becomes the Professor’s staunchest supporter.

But is this just a calculated bid for sympathy by the wily Professor? Later it turns out that he does have a family: he shows a torn, faded photograph of his sons to Niobe. And the question of whether he actually cares about the workers as individuals, or only about his ideals, remains open. At times, he seems startlingly callous, as when he shows up at a wake for Pautasso (Folco Lulli), a worker killed during a fight with scabs in a railyard, and asks, “Why all the long faces?” Brandishing a newspaper, he triumphantly tells them that the factory owners are taking a beating in the press. Raoul, meanwhile, comes to the wake and finds Pautasso’s daughter, Adele (Gabriella Giorgelli), weeping alone in another room. He has spent the movie crudely teasing her, like a schoolboy tormenting a girl he has a crush on, and consoling himself with other, more-than-willing young women. But now he kneels down beside Adele and tenderly brushes the tears from her cheeks with his fingertips. It is hard to picture Mastroianni, for all his versatility and brilliance, pulling off this moment the way a big lug like Salvatori can; Mastroianni is almost incapable of doing anything simple on screen. The Professor is slyly intelligent and capable of incendiary eloquence, but remains deeply ambiguous. Beneath the eccentric mannerisms, he seems opaque and inscrutable, possibly hard—perhaps this too is why the smooth wooden egg is a good symbol for him.

While the English title The Organizer elevates one individual, the original title, I Compagni (“The Comrades”), makes clear the real subject is the group. But the darning egg contains another meaning that encompasses them all. It is a humble, traditional object used for mending by hand, and as such offers the greatest possible contrast to the huge, dehumanizing machines in the textile mill. Monicelli shot inside a real factory outside Turin, a vast cavernous space filled with the din and clatter of wheels, belts, gears, and mechanical looms, all in constant, relentless motion. The workers are chained to these machines for 14 hours a day, their lives and bodies governed by the whistle. Their initial demands are modest: they would like a 13-hour day and accident insurance for those who are maimed. Progress has been made in labor rights (at least in western countries), but the workers in today’s factories and Amazon fulfillment centers are still prisoners of the same imperative: to churn out new goods for consumption. The ethos of mending and repairing, of making by hand and making do with scarcity, is more than foreign in our society, it is almost taboo. Hence, the Professor’s ratty long underwear, Swiss-cheese gloves, and darned socks register as a protest.

There is a long history of using images of the homes and pitiful belongings of the poor to show “how the other half lives,” from Jacob Riis’s shocking photographs of immigrants on the Lower East Side living in coal cellars to Walker Evans’s plain, lucid pictures of Southern sharecroppers’ weathered-plank cabins, flyspecked sheets, and burlap-sack dresses. A Riis-like anger flares up in The Organizer when the camera enters the squalid hovel where a Sicilian migrant worker and his family live, and the sharpest cut in the movie goes from a shot of a filthy baby crying on the dirt floor to well-dressed young people playing party games at the mansion of the factory owner. It is as subtle as the blow of an axe, and the film is blunt in its contempt for the bosses, who are smarmy, deceitful, and entirely unmoved by the plight of their workers.

Are we defined by what we own? In Monicelli’s The Passionate Thief (1960), Anna Magnani has a telling line when her character, a hapless movie extra, winds up through a series of misadventures in the home of a wealthy German family during a New Year’s Eve party. She observes that the rich are characterized by “their love of beautiful, useless things.” An overabundance of objects is often used in films to advertise the oppressive soullessness of wealth, as in Citizen Kane or the late films of Luchino Visconti, where aristocrats appear suffocated by the lavishness of their surroundings. By contrast, the most precious objects are scarce and functional—not glittering baubles in a vitrine like those that inspire Magnani’s line, but things that are held and carried and used, things that are necessary.

When actors can convince us not just that the items they handle are real, per Mitchum’s theory, but that they are familiar and personal, their characters deepen. The things we live with and use daily—hairbrushes, cups, pens, clothes—become extensions of us. We shape them through use and wear, but they also shape us—our consciousness is knitted around them, like a sock around a darning egg. It is this intimate relationship, illustrated by the Professor’s anxious concern for his little basket of “necessities,” that explains why objects are so important in Monicelli’s movies, though they are all about people.

Interactions between people and things are always a fertile field for comedy: when one of the strikers in The Organizer spits on a horseshoe and tosses it out the window for luck, of course it beans a fellow worker. Some left-wing critics objected to the laughs in The Organizer, finding it inappropriate to mix humor with such serious subjects as the exploitation of workers and the necessity of collective action. But comedy was integral to Monicelli’s humanism: he knew that people are only people, and no matter how much they suffer or how noble their cause, they will still act foolishly, and any group that tries to come together for a common effort—whether a heist, a war, or a strike—will face bickering, conflicts, and betrayals. Monicelli said that all his best films were about failure, but they are also about how people keep going and make do, like the bumbling gang in Big Deal on Madonna Street savoring a nice pot of pasta and beans amid the wreck of their elaborately planned caper, or Raoul jumping on a freight train with a bundle, setting off to become another wandering agitator. The Professor ends the film in jail. At least he will have plenty of time to mend his socks.