Digital Art

Matt Connolly on The Royal Tenenbaums

“The doll-house aesthetic.” Few phrases dominate the critical discussion of a filmmaker more than this expression does for Wes Anderson, and not without some justification. It helpfully articulates his compulsion for natty pictorial detail, his penchant for filming with diorama-esque geometrical precision, his impulse to encase his cinematic worlds within a lovingly, obsessively wrought structure of his own making. Depending on the viewer, its evocation of childlike control and dusty nostalgia signals either an appreciation of Anderson’s singular filmic realms or an exhaustion with his visual noodling that comes at the expense of engagement with the lived world.

I often bristle at the more cavalier dismissals of the director’s work as overly precious and lacking in emotional depth. To claim that Anderson’s relationship to the various gewgaws and knickknacks that populate his films consists solely of myopic fetishism overlooks how they actively interrogate the relationships between people, the objects they fixate upon, and the unresolved traumas those fixations both exacerbate and obscure. Certainly, Anderson relishes finding and crafting nostalgia-infused items that he can then place within immaculately coordinated fictional spaces. Perhaps it takes someone with his curatorial compulsions to appreciate how those bespoke baubles embody his protagonists’ agonies, shortcomings, and desperate desires for belonging. I can think of no better example than a particular object in The Royal Tenenbaums, a totem of psychic hurt that’s also the literal extension of a wounded body.

Even in a family as profoundly dysfunctional as the one at the center of Anderson’s 2001 film, Margot Tenenbaum (Gwyneth Paltrow) stands out for the sheer depths of her isolation. Like adult siblings Chas (Ben Stiller) and Richie (Luke Wilson), she was once deemed a youthful prodigy—in her case, for playwriting—though her status as the Tenenbaum’s sole adopted child instilled a sense of separation that drove her to secrecy and aloofness. Her acts of rebellion continue into adulthood and long after her theatrical career fizzled, ranging from a clandestine, multi-decade smoking habit to globe-hopping sexual rendezvous to her current marriage to an older man, the befuddled neurologist Raleigh St. Clair (Bill Murray). A further element marks Margot as different from the rest of the Tenenbaum clan: a wooden digit attached to her right hand that replaces the ring finger she lost in an ill-fated attempt to reconnect with her biological family. The finger itself cannot be mistaken as anything but ersatz. While broadly shaped like its fleshly counterparts, its brown color, slightly oversized girth, and visible grain make it appear as if crafted from a tree trunk. That it appears to be attached to Margot’s hand via a thin white bandage further underscores its ambient absurdity.

Rather than being asked to think of Margot’s prosthetic in a tactile or practical sense, the viewer is initially invited to see it as a purely visual device, operating somewhere between oddball character detail and sight gag. These connected impulses can be seen in other choices. Most of the protagonists in The Royal Tenenbaums wear variations on the same ensembles throughout the film, with Margot’s blue horizontal striped dress, calf-length fur coat, and raccoon-eye makeup offering an especially striking example. While one can argue for thematic resonances in these choices (the frozen-in-time outfits manifesting the Tenenbaum children’s inability to escape their wunderkind pasts), it just as strongly points to Anderson’s propensity for a kind of totalizing aesthetic control that extends to the bodies of his performers. At the same time, his fondness for distancing formal devices—long-shot tableaux framings, droll voiceover narration, montages of labeled items and events—can make these fussed-over figures look ludicrous or even pitiful, ornately decked-out butterflies pinned to the board of Anderson’s mise-en-scène.

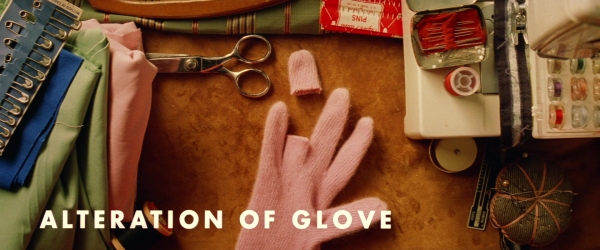

Artificially augmented anatomy can feel like the next grimly logical step in Anderson’s object-ification of his characters. The initial explanation of the digit’s presence comes indirectly, furthering a sense of detachment. The Royal Tenenbaums opens with an extended prologue that catches the viewer up on the family’s past glories and present failures: the siblings’ various adolescent triumphs, the management of the children’s burgeoning careers by mother Etheline (Anjelica Huston), and the emotional wreckage left behind by louche patriarch and ex-husband Royal (Gene Hackman). Narrated with cracked-ice dryness by Alec Baldwin, this preamble mentions in passing how teenage Margot “disappeared alone for two weeks and came back with half a finger missing.” The film does not visualize this bodily mutilation by showing the incident itself (not yet anyway) but rather cuts to a by-now patented Anderson image. An overhead view captures a single white glove with the ring finger sliced off around the knuckle, surrounded by carefully arranged bolts of fabric, spools of thread and a pair of silver scissors. “Alteration of Glove” reads the on-screen text in white capital letters. It’s an almost too-perfect iteration of Anderson’s impulse to gesture toward the bloody mess of reality with a fabricated stand-in that can be labeled and coordinated, fussed over and snickered at.

The miracle of The Royal Tenenbaums comes in how it actively pushes against these aesthetic constrictions, the tensions between lived experience as an amber-encased collection of relics and a vibrantly messy collision of bodies built into the film’s storytelling. Margot’s finger offers a rich instance of these dynamics. Our first real glimpse of the imitation digit comes when adult Margot sits on the bathroom sink, hiding away from her doting, dumbfounded husband behind the locked door. When Raleigh manages to stick his head in and attempts to coax her out for dinner, Margot demurs in a typically affectless manner. The one marker of her anxiety comes in the nervous strumming of her fingers against the side of the porcelain sink, the near-silent padding of her fleshly digits broken by the hollow click of her wooden one. Anderson underscores the humor of this moment with a cut to Margot’s hand in motion but returns immediately to a close-up of her placid, plaintive face. The tell-tale tap becomes the one crack in Margot’s armor of studied listlessness, her body sending out an SOS in spite of itself.

Margot’s wooden finger purposefully stands out in these earlier scenes, but it becomes one of innumerable props within the frame as the film progresses. Margot moves back into her parents’ home to sort out her feelings about her marriage, her ongoing affair with Tenenbaum family friend Eli Cash (Owen Wilson), and the general malaise that has settled over her life like a fog. Chas has also returned to the nest out of concern for his twin boys’ safety following his wife’s death, while Richie’s homecoming is precipitated by Royal’s cancer diagnosis, a lie concocted by Royal to reconnect with his estranged family and get some free lodging after being kicked out of his long-term-stay hotel. (Richie is also contending with his taboo but persistent romantic love for his adopted sister.) Stacks of dusty board games, faded paintings, and bookcases filled with obscure tomes pervade the Tenenbaum household and become a psychic minefield for the family. Long-simmering resentments bubble to the surface as they maneuver around both one another and the piles of stuff that are both nostalgic souvenirs of bygone brilliance and bitter reminders of its present absence. The thickness of Anderson’s visual design means that frequently no single item dominates the frame. This leads to Margot’s finger often forming but one piece of the mosaics that constitute a given image. An overhead framing (but of course) of Margot’s right hand cueing up a record on an old-style turntable is amongst the clearest shots the viewer gets of her faux digit in the back half of the film, yet in this shot it registers as merely part of the jumble: spaceship wallpaper, aging carpet, Rolling Stones album cover, vintage toy cars, athletic trophies, dog-eared family portrait. The impulse to overly fetishize any single object becomes overtaken by the sheer density of objects themselves, turning what might have been a punchline into something oddly at home in a world defined by accumulation and curation.

When The Royal Tenenbaums discloses the origins of Margot’s finger, meanwhile, it does so in a manner whose apparent glibness masks a deeper, odder hurt. She unspools the tale to Chas’s sons when one asks point-blank about her injury: a misbegotten journey to rural Indiana that 14-year-old Margot took to reconnect with her biological parents. Anderson flashes back to the fish-out-of-water reunion, with Margot’s large and vaguely Amish birth family attempting to integrate their decidedly metropolitan daughter (complete with black dress and fur coat) by having her help split logs. The unnamed father instructs “sister Maggie” to hold a hickory trunk while he slices it in two, not realizing that Margot’s hand remained in the path of the blade. The suddenness of the accident and the quick return to Margot’s present-day musings edges the scene close to flippancy (“Wasn’t worth it,” she sighs when one of Chas’s sons asks if she tried to sew her ring finger back on.)

Yet the moment also acts as the key to unlocking both the profoundness of Margot’s isolation and the melancholy connection she nevertheless shares with her siblings. The woodsy milieu in which Margot lost her finger seems to motivate the peculiar material of its replacement. If the presence of this eccentric prosthetic physically marks Margot’s separation from the Tenenbaum clan, its substance ironically reveals her alienation from her biological family as well—one that is also made up of multiple siblings and a clueless, destructive patriarch. She is tied to both yet a member of neither. What ultimately links Margot to her brothers is the pain through which she gained her wooden digit. Both Chas and Richie also have their hands marked by scars that flowed from familial suffering. A BB remains lodged between two of Chas’s knuckles after Royal shot him as a child. Richie’s all-consuming love for Margot leads him to first punch through a pane of glass and eventually attempt suicide by cutting his wrists. That Margot’s violent trauma remains so tactile, an object fixed to her body, only accentuates how all three Tenenbaum children both exhibit and sublimate their wounds over the course of the film.

Literally attaching a prop to a character’s hand implies a directorial desire to micromanage the appearance and movement of his actors, yet Paltrow in The Royal Tenenbaums offers a rich example of how Anderson’s control-freak aesthetic paradoxically works best when inhabited by strong, idiosyncratic performers. The most affecting moments for me come when actors are able to simultaneously attune themselves to Anderson’s wavelength and convey in their distinct fashions the deep feeling churning under the pastel-colored surfaces and deadpan diction. Paltrow relishes the almost mannequin-like stillness with which Margot inhabits space, registering not just lethargy but a Bartleby-like refusal to engage in life. Her air of obstinate indolence adds another level of comic poignance to Margot’s wooden digit, literally giving the finger to anyone who would question its ungainly presence. Paltrow understands the work that Anderson’s meticulous costume and prop design does for her as an actor. At the same time, subtle shifts of her eyes, face, and body create the required emotional frisson to make Margot more than a sad-eyed emblem of glamorous torpor. She exposes the wells of vulnerability beneath Margot’s placid exterior, hinting at the secret worlds of hurt and hope that exceed even what is revealed by film’s end.

This is never more apparent than in Margot’s last major scene with Richie. The two slip away from the wedding celebration between Etheline and kindly accountant Henry (Danny Glover) and end up on the roof of their childhood home. Richie and Margot have earlier acknowledged their mutual love but remain uncertain about where that leaves them. In a rare candid moment, Margot lifts a brick to unveil one of the numerous places she’s hid her cigarettes over the years. (She’s vowed to quit, but sighs that her nicotine inhaler has thus far done little good.) A conspiratorial smile flashes across her face as she pulls out two cigarettes, lights them both, and passes one to Richie. They raise their hands in unison and each take a long drag. One cannot help but notice the single crucial difference in their otherwise-mirrored right hands, yet now that faux finger appears less a scarlet letter (even less a joke) than a badge of wounded survival. Perhaps the things carried by Anderson’s characters will never lose their freighted history, but they can be shared, examined, and used to inch into the future. Out of these objects, one might end up finding a design for living.