Man in the Middle

by Jeff Reichert

Mr. Landsbergis

Dir. Sergei Loznitsa, Lithuania/Netherlands/Ukraine, no distributor

Mr. Landsbergis plays Saturday, March 19 at Museum of the Moving Image as part of First Look 2022.

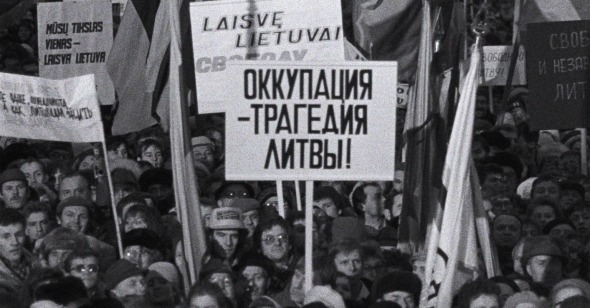

Sergei Loznitsa’s massive new archival-based film Mr. Landsbergis is mounted with remarkable confidence. Over the course of four hours, the Ukrainian filmmaker constructs a granular record of Lithuania’s moves towards independence, from rumblings and street protests in 1988, through boldly declaring its statehood in 1990, and then, finally, the bloody but failed 1991 attempt by the Soviets to topple the new government as the U.S.S.R had begun to actively crumble. At the film’s center, appearing both in archival material and in a present-day seated interview that periodically breaks the flow of historical images, is Vytautas Landsbergis, leader of his country’s Sąjūdis reform and independence movement, later elected the first Head of Parliament for the newly re-created Lithuania.

Now aged 89, the genial Landsbergis, framed by Loznitsa seated in an untucked, rumpled, short-sleeve blue shirt in a sunlit garden, reads more as a retired accountant or middle-school science teacher than a revolutionary possessing a will iron enough to repeatedly buck the Soviets. Even in his heyday, as leader of Sąjūdis, he cut a surprising figure: short, dwarfed by a puffy leather coat, his face hidden behind chunky glasses and a patchy goatee, an occasional loud tie suggesting some boldness of his inner character. Yet, this unremarkable fellow, a conservatory-trained university professor at the outset of the independence movement, seems throughout Mr. Landsbergis an utterly immovable object, whether throwing the lie of perestroika in the face of the entire Party in Moscow during a speech before the first Congress of Peoples’ Deputies, or showing his stolid implacability in those dire hours in January 1991 when, with Soviet troops advancing, he presided over the deputization of dozens of men into the military to help defend Lithuania’s nascent government. Late in the film, Loznitsa asks Landsbergis if he was ever scared through all of this, and his simple “no” rings believably.

Landsbergis, though he is afforded the title of the film, is positioned less as its main subject than as a wily raconteur and guide, quick to chuckle at the repeated fumbles of Gorbachev, whom he clearly finds foolish, in managing Lithuania’s breakaway, or to acknowledge when a lapse in his own memory might require him to look up this or that fact later. It isn’t until late in the film that Loznitsa makes attempts to unpack Landsbergis’s subjective experience. “Did he want to be politician?”—no, Landsbergis, pianist, chess player, Ph.D., and ultimately longtime member of the EU Parliament, only wanted to live his life and raise his children. History intruded. In a subtle yet striking formal choice, the interview does not overlay the archival, which allows both strands to breathe, and never reduces Landsbergis’s reflections to mere color commentary.

Though Landsbergis clearly has star quality, as in Loznitsa’s other recent archival works the main subject here is history: the process of attempting to capture it, arrange it fairly and with little obvious manipulation, and recommunicate it to an audience. The range of cinematic tools the filmmaker is deploying—vérité archival, the master interview with Landsbergis, occasional text cards on-screen bearing dates or questions—is small; there’s no cheekily deployed period music or infantilizing animated sequences here, no obvious moments where montage is utilized to skip viewers across time or condense complicated ideas. Instead, as in The Event and State Funeral, there is emphasis on linearity and letting the archival material lead the way, with long scenes filmed from multiple cameras on different formats intercut. Even if this approach occasionally means some events are left opaque to viewers, the minute-to-minute sense is of history as it happened. Loznitsa clearly has a massive caché of footage to mold and shape at his disposal—in many sequences one might spy black-and-white and color video of various flavors abutting scarily pristine 16mm, also with and without color.

There’s an excitement when the film’s edits (managed by Danielius Kokanauskis, who also cut State Funeral amongst other Loznitsa films) switch formats but manage to capture the same or ever-so-slightly different angle on the events—this akin to the pleasure we might find in a fiction film that skillfully moves us through space. Some cuts reveal a glimpse of the previous camera as it ducks out of frame, and with it, the sense of real physical bodies jostling in space to capture the important image. As in the exhaustive (also, exhausting), State Funeral, these intersections in the footage make one marvel at the amount of cameras that were around, and question just who all these images were being collected for. In these films, there’s a suggestion of a culture obsessed with documentation and recording. This makes sense—Landsbergis refers to the U.S.S.R as the “Empire of Lies,” and what better weapon to make the case for the truth, or, conversely, perpetuate specific lies, than recorded images?

Loznitsa’s fidelity to events, and emphasis on building out those moments when he can make multiple different footage sources intersect through editing, don’t always leave room for visual poetry or perhaps an unexpected aesthetic movement that might have opened up the viewing experience. Though perhaps, for the eminently logical Loznitsa, a former engineer of A.I. and related systems, locating these intersections in the body of the archive and colliding them represents his own brand of poetic fancy. The filmmaker, almost stubbornly, always admirably, adheres to the template he sets up early in the film. Yet, it is thanks to this rigor that the unrelentingly dense Mr. Landsbergis never feels taxing. If the massed history unfolding at times overwhelms, it’s never long before Landsbergis, a great undersung recent hero of democracy, smiling and wry, reappears to recenter our viewing. This film is a testament to his leadership that never allows the personal to overwhelm the complicated historical machinations its images so compellingly reveal.