James Crawford

In ten years time, we may well look back at Zodiac as a landmark evolution in shooting (in) the dark—a problem that cinematographers have never adequately solved.

"The cult of the genius is one of the movie’s subjects, but he considers himself to be an artist, and therefore the objects of attraction that become his victims are just elements of a sculpture. In his amoral perspective, he never really considers them to be victims."

Clocking in at a shade over twelve and a half hours, Jacques Rivette’s behemoth certainly is daunting for all the reasons one might expect, but then again not: unlike Bela Tarr’s seven-hour Sátántangó, the film is not intended to be consumed in a single sitting.

Like Godard, Rivette works like an analytical reverse engineer, picking apart the cinema and leaving its part strewn about.

The Fury is an urban reworking of Carrie’s notion of young adulthood as physical and psychological trauma.

Lattuada plumbs material that a director like Visconti would mine for social realism, and takes a much more lighthearted view.

The title, Gardens in Autumn, evokes stopping, if not to smell the roses, then at least to watch the leaves change color (Iosseliani himself shows up onscreen as the man who tends that garden).

Given its mercurial tendencies, Matador demands rapt and unwavering attention, and not a little bit of patience, because one is never sure of a moment’s disposition (or position with respect to the whole) until that moment has fully played itself out.

Before Little Children, I had no idea that our most outwardly benign enclaves are tainted by…by…philanderers, both male and female; pedophiles; mail-order johns; gays (!); and transvestites (!!)—in short, sexual deviants of every imaginable stripe.

Now that Pedro Almodovar has spent close to a decade working in his idiom of dark, fraught melodramas, it’s easy to forget the vitality of his early films.

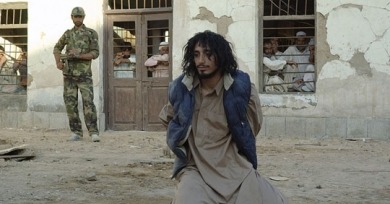

"For me life is a competition; even if we don’t want to, we have to do this thing. To wake up, to go to your work…even if we don’t need these things, we have to do them. Life is working by elimination—you need this job, I want to do this movie—it means I’m gonna have to do better than someone else."

Much to my great dismay, Richard Linklater’s heady, intelligent, beautifully empathic vision of a rather quotidian and familiar dystopia is in the running to be the least appreciated film of the summer.

There’s little, narratively speaking, to suggest a work of weight and nuance, and yet Oswald accomplishes it, crafting a visually complex film. It all begins with the film’s second shot.

The Dardenne brothers’ L’Enfant has been justly hailed as a brilliant work, but for gritty observational verisimilitude The Death of Mr. Lazarescu outstrips it at every turn.

I came late to Lynch because I never had a film-obsessed companion to insist that my life wasn’t complete until I’d seen Blue Velvet or The Elephant Man, which seems to be how most burgeoning film critics are drawn into his peculiar universe.

Jim Jarmusch, one of the last bastions of truly independent American cinema and director of the 2005 Cannes Grand Prix–winner Broken Flowers, is an elusive interview.

Because of its prefacing epigram, Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Café Lumiere has drawn a barrage of comparisons to Yasujiro Ozu. Hou dedicated his film to the occasion of Ozu’s birth centenary, but upon further reflection, it seems like a ploy to shut the public up.