Sweet Liberty

By James Crawford

Gardens in Autumn

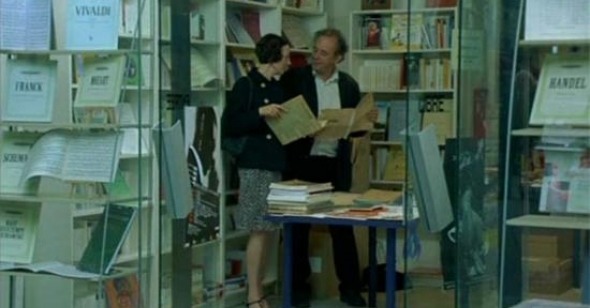

Dir. Otar Iosseliani, Italy, no distributor

Two releases at the New York Film Festival are built in homage to Luis Buñuel: Belle toujours, Manoel de Oliveira’s grammatical gloss on Bunuel’s most notorious film, which reaches back into the murky depths of celluloid memory to interpret, understand, and recapture a particular moment in time, and Gardens in Autumn, Otar Iosseliani’s entirely straight-up (which is to say delirious) replaying of the director’s less serious efforts. Gardens in Autumn shares a lot of the same genetic material as Buñuel’s later, for a lack of a better word, “surrealist” films, which perhaps are better thought of as feverish works where nothing happens at a furious pace. Gardens in Autumn vibrates with the frippery of The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and That Obscure Object of Desire, which are incisive, but gently so, situating a host of various bourgeois/nouveau-riche critiques under a veil of absurdity. With characters directly involved in politics or otherwise connected to upper echelons of power, Bunuel’s critique was usually dispersed at a social level; it’s the mark of modern solipsism that Iosseliani takes his perpetually, sweetly bizarre universe and makes it mere background noise for the travails of just one man whose life’s been thrown more than a little out of whack.

The first element abstracted in a series of abstractions, is the public, which Iosseliani conceives as being both symbolic and immensely powerful. Based on their vehement protests (of what?) in the streets of Paris, Vincent (Séverin Blanchet), a French government minister (of what?), is ousted from his post, chosen by a government visually in absentia, to fall on the sword for its manifold, untold ills. Instead of this being a destabilizing event, Vincent finds it liberating. Life in the city is already unhinged—old men shop for coffins and hunters shoot at wildebeest on the outskirts of Paris. His label-whore wife leaves him for his most ardent political rival, and he has no employment possibilities, which leaves ample time for affairs with a host of former lovers and for reconnecting with his family.

It sounds like a quintessentially masculine midlife crisis film, in which the one-dimensional career man finds truth and transcendence by re-examining the basic tenets of his life. The title, Gardens in Autumn, evokes stopping, if not to smell the roses, then at least to watch the leaves change color (Iosseliani himself shows up onscreen as the man who tends that garden); and yes, the film recalls the early French New Wave in that the film’s women, in debilitating, unreciprocated thrall to Vincent are as interchangeable as spare car parts. But Iosseliani is insistent in taking delight in almost everything Vincent touches, evoking Buñuel by playing a relatively straightforward visual structure against weird characters, and the even weirder things they say and do. Kicked out of his government residence, Vincent tries to return to his family home only to find it squatted by an African family whose sole Caucasian inhabitant, a skeletal septuagenarian, empties his daily excrement out the window like a Victorian maid tossing chamber pot contents. Vincent, for his part, relieves stress by doing headstands at the most inopportune times while his adversary and romantic interloper keeps a sleepy, lounging leopard around the house.

By far the greatest of all these pleasures though, is the appearance of Michel Piccoli, who gives this festival’s single greatest supporting performance, dressed in drag, as Vincent’s mother, Marie. Though matronly and rotund after the prototype of most aging French actors, Piccoli, wearing shapeless floral print dresses, is overly solicitous, coquettish, and birdlike, perching rather than sitting on any horizontal substance onto which he deposits his considerable girth, and ambling stiff-legged like an arthritic dame. In short, he does nothing more or less than fully, unconsciously inhabit the persona of a dotty, doting grand-mère. It’s absolutely hilarious, and it manages to completely obliterate the memory of Piccoli’s greasy sexual potency in Belle de Jour, or even his nonpareil, smoothly debonair turn in the NYFF entry Belle toujours. But because the family is entirely oblivious to (or entirely at ease with) Piccoli wearing women’s clothes, I was never certain whether Piccoli was supposed to be a woman played by a man, or whether within the world of the film, he was a man who simply dressed in women’s clothing.

The joyful absurdity of Gardens in Autumn is that both are equally possible. Contrast that feminized version of Piccoli, a onetime sex symbol, with the new lover of Vincent’s wife: a bald-by-choice tough guy (think a Gallic Kojak), whose posturing, sneering virility (best embodied by that leopard) is undercut by the pristine silk scarf he effetely drapes around his neck. So if there is a method to Iosseliani’s madness, it’s to redress the idea of absolute masculinity. Conversely, since the government depicted is, by way of synecdoche, reduced to a handful of inept individuals, calling out the failings of public institutions might be the other. Though really, overrun by such unabashed glee at its own moment-to-moment ridiculousness, Gardens in Autumn never truly approaches the level of sustained, rigorous critique.Whether deliberately or incidentally, Otar Iosseliani’s film is a palliative to the strained, super-seriousness of middle-class, middlebrow dramas—the worst, most recent example of which has to be another festival release, Todd Field’s Little Children By contrast to that piece of epically bombastic excrement, Gardens in Autumn arrives at some kind of skewed coherence, not through obtrusive mechanics but by indirection and graceful, bemused scrutiny.