Poetic Injustice

By James Crawford

The Road to Guantanamo

Dir. Michael Winterbottom, Mat Whitecross, UK, Roadside Attractions

The word “muckraking” currently sits at a peculiar crossroads. The term has fallen out of favor—much as “propaganda,” which in its 18th-century definition is innocuous enough, became taboo because of its unfortunate use to describe systematic fascist (and, to be fair, Allied) (dis)information campaigns during World War II. Hence muckrakers are considered the very worst journalists, bent on dredging up dirt for the purposes of cheap sensationalism and profit-motivated scandal mongering. And yet with the current proliferation and democratization of media outlets, this discourse couldn’t be more popular. As with rampant blogging, which is not necessarily subject to journalism’s traditional strictures of accountability, the entry barriers to documentary filmmaking are so low—a video camera, a modicum of intelligence, a half-baked argument and you’re all set—that theaters are awash in essay films shot on the cheap and girded by rhetorical skills that’d make a high-school student blush. But even the most rigorous, airtight works of social activism—exemplars The Corporation and The Future of Food come to mind—are still deficient when it comes to eliciting emotion. Because they function primarily as personal essays, they by definition are meant to view their subjects with an objective remove and to not traffic in emotions. They’re rather clinical vehicles to provoke outrage and action, not to evince affect and sympathy.

Michael Winterbottom and Mat Whitecross’s The Road to Guantanamo, a docudrama that satisfies both halves of the genre, is muckrake par excellence, bringing to light a saliently deplorable instance of military and political wrongdoing, and it treats the experience of those who’ve suffered injustice as something that should also be laid bare—represented, and not abstracted through reporting. Put another way, Winterbottom and Whitecross are canny enough to deploy the one-two punch of both showing and telling, making for a remarkable fact-fiction hybrid.

In all fairness, the events depicted in The Road to Guantanamo, being among the most flagrant and well-documented human rights violations since the “War on Terror” began, are easy to denounce. In late September 2001, four British twentysomethings of Pakistani descent (Ruhel, Asif, Shafiq and Monir) travelled to Karachi to celebrate Asif’s marriage. Urged by an Imam at a Karachi mosque, the four ventured over the border into Afghanistan, with humanitarian intent—fully cognizant that at the time, the country was one of the most dangerous places on earth, because of nightly U.S. bombing campaigns and an ongoing war between the Taliban and the U.S.-backed Northern Alliance (NA). By what can only be termed the worst luck imaginable, three of the four found their way into a Taliban stronghold and subsequently NA captivity, having been mistaken for Taliban soldiers. (Monir gets separated during the nighttime bombing of an evacuation convoy and is never heard from again.) Even after their identity as British nationals is revealed, the “Tipton Three,” so named after their hometown near Birmingham, are sent to an outdoor prison at Sherberghan, subsequently shackled and sent off to Khandahar and finally to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, home to some of the supposedly worst terrorist operatives in U.S. custody. The Tipton Three clearly have nothing to do with any atrocities, and yet they’re subject to deplorable conditions beyond the scope of human understanding and endurance: sleep deprivation, sensory deprivation, sensory overload (death metal and strobe lights in one shocking example), enforced silence, stress positions held for hours on end, intimidation by dogs, and relentless interrogation. The Tipton Three are vaguely (and groundlessly) suspected as being in league with Osama bin Laden. As “enemy combatants,” they are denied legal counsel and held for months without official charges, and the barest mentions of habeas corpus or due process are summarily laughed out of the room.

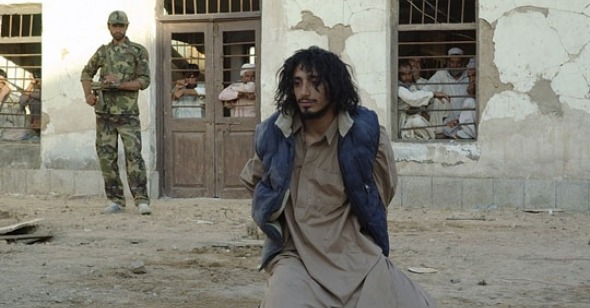

Because these events, interspersed with interviews with the real Ruhel, Asif, and Safiq, are fictionally re-enacted by actors in digital video, Guantanamo has strong affinities with Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line. But the particular relationship that Winterbottom and Whitecross’s film has with such fraught concepts as “truth” and “reality” is pretty much sui generis. Morris’s hyperbolically saturated re-enactments, showed alternate possible truths to reflect the rampant equivocation and falsehoods betrayed during interviews with its subjects. Guantanamo is absolutely convinced that Ruhel et al are telling the truth of their imprisonment, and so lets the fiction of their film stand as a proxy for the truth. The strategy is outwardly troubling—fiction masquerading as reality, a la Stephen Glass and Jayson Blair, is journalism’s worst offence (and from a theoretical standpoint, it smacks of Bazin buffoonishly claiming that the photograph of an object is inherently more real than the object itself)—but not under the rubric of Winterbottom and Whitecross. The grainy, urgent, footage of the fictional Tipton Three, possesses a degree of indexical reality and immediacy for its being shot on location in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and is a way to convey the visceral fact of their harrowing experiences. Moreover, since the story of Ruhel and company pretty much squares with the official assays of Amnesty International and the Red Cross, quibbles over truth and fiction are rendered moot.

In a film as important as Guantanamo, one wishes that its advocacy was airtight, and that’s not always the case. Being British nationals, Winterbottom and Whitecross assign their own military complicity in the Guantanamo affair. And rhetorically, I have one major reservation: the voice of the film’s narrator is awfully similar to that of the BBC’s newscaster who reports developments in the war on terror. As such there’s an indeterminacy as to whether the voice-overs are the reporting of Britain’s media of record or the opinions of the filmmakers themselves. Still, such objections seem trivial in the face of a film remarkably free of overt authorial opinion, save the occasional clip of speeches from the Bush II administration, which are included for ironic commentary. The certitude of Bush (“All I know is that these are bad people”) and Rumsfeld (“There is no doubt in my mind that the treatment is humane and appropriate and consistent with the Geneva Convention, for the most part”) in the face of what the Tipton Three endured, is nothing short of shameful.

As something of an epilogue, it’s important to note that Ruhel, Asif, and Shafiq were released in Great Britain in March 2004, after nearly two and a half years of imprisonment—without recourse to any of the legal rights normally guaranteed as certain in a free and democratic society. They were never charged with any crimes, and yet the U.S. government remains steadfast in its denial of any wrongdoing. More than any other film, The Road to Guantanamo makes palpable Benjamin Franklin’s axiom, “Those who would give up essential liberty, to purchase a little temporary safety, deserve neither liberty nor safety.”