Summer of ’81

Serge Daney once described Le Pont du Nord as the first French film of the eighties, suggesting that it marked the beginning of a new period in which the filmmakers that had burst onto the scene in the sixties returned to their roots.

Jimmy Caan was not an icon. He was a guy you knew or met and never forgot, and remembered in your body, your insecurities, your impulses.

Cronenberg lets questions accumulate like a haze: at what point in a mutation do we remain recognizably human, something else, or somewhere in between? Will we look back and laugh at our quaint fear of change, or is that what makes us us?

Blake Edwards condensed all his exhaustion into the majestically profane S.O.B. He channeled the pent-up sexual and artistic frustrations of an era in both his own career and filmmaking culture at large and let loose with a provocation that heralded the new order to come.

Watching these films again in 2022 reveals a poignant congruence with the deficiencies of the world today and prompts a deeper set of questions about humanity’s ability to govern itself.

When his suburban melodrama The Woman Next Door was released in 1981, Truffaut was, in many respects, getting back into his stride.

Bronx-born, Pittsburgh-forged George A. Romero is the possessor of one of the odder filmographies in American movies, and Knightriders, which trades undead hordes and jump scares for gallant knights and plainspoken earnestness, is an outlier.

Lou and Sally’s bond feels not like a fated union between soulmates betrayed by time but a fleeting intersection of two souls on decisively separate paths. Atlantic City is the run-down playground where this meeting is made possible.

The dialectic between the two characters aptly captures the internal schisms of the 1970s western left, but von Trotta never reduces the women or their relationship to an intellectual exercise. This is a film of ideas with a wounded human heart.

Go-motion itself was but a small part of the films it was deployed in, used to complement other techniques and props. It makes sense that such puppets would be deployed as a special effect in fantasy films that flirt with the macabre, go-motion becoming a sort of necromancy itself.

Sara Driver’s film feels more beholden to the work of Maya Deren and Jean Cocteau than the coming wave of American independent movies that would transform the decade.

The brilliance of Modern Romance lies in how Brooks, as the film’s co-writer, conflates the comedic and horrific implications of its romantic premise until they are indistinguishable from one another. The film is funny because it’s kind of disturbing, not despite that fact.

Francine is holding on for dear life as her nuclear family falls into disarray with a cheating porno theater-owning husband, a fetishistic teenage son who gains local notoriety for stomping on feet, and a rebellious daughter with an unplanned pregnancy. Francine is unloved, ignored, and routinely humiliated.

The Fox and the Hound belongs to what has been unofficially deemed the Dark Ages of the studio, those 18 years that commenced shortly after Disney’s death and proved, with some exceptions, generally less popular, either critically or financially.

Made at the height-to-date of the New York crisis of violence, it responds with a story steeped in simplistic moralism and frank bloodlust. It is black and white and red all over, like the front page of the New York Post, that eternal foot soldier in the culture war.

Part of its dark power inheres in its slippery, tentacular relation to its own genres and themes. Repeatedly, the film lunges at an idea or stakes out a tone, each offering plenty to chew on, but then pounces just as fiercely in some transverse direction.

The sweltering love affair at the center of Body Heat is one of both bodily and economic exchange. Each person, it turns out, wants something more from the other than meets the eye: not just a mistress but a loaded one; not just a boyfriend but a patsy.

Despite the extensive tampering of its producer, Orion Pictures, Wolfen should be considered one of the most remarkable and visually innovative Hollywood films to be released in 1981.

Released in August 1981, it would be a turning point for special effects and for creature narratives in the coming decades, where the grotesque and profane meld together into something a little snide and ironic.

Like the sunglasses in a later John Carpenter film, They Live, through which the messages of ideology become bluntly visible, the western in Escape from New York focuses and clarifies the contradictions of a new and pernicious political reality.

You could call it a 1970s hangover movie: the triumphant colors of Mur murs have washed out. Even the beach looks bleached, and the celebratory, rebellious atmosphere has turned to quiet defeat.

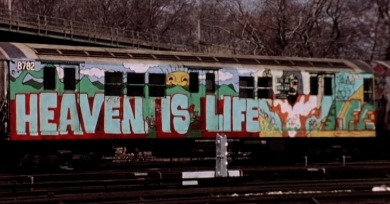

You can feel the sense of chaos in the cacophonous trains festooned with graffiti, bulbous fonts and enigmatic emblems and cartoonish signatures. Kirchheimer distills the essence of the city into 45 minutes of trains trundling along, piebald in paint; the film is a beguiling sequence of 16mm images.

Cinematically it is neither here nor there, sandwiched between agreed-upon renaissances. There were marvels, there were duds, there were mediocrities, like any year... Yet we discovered 1981 feels as much like a turning point as it does a middling cinematic interzone.