Subway Stories

Greg Cwik on Stations of the Elevated

The train rattles in the dark, aching like old bones. Any New Yorker knows the sound: wheels screeching, metal-on-metal as you round the corner. The etchings in the glass, doodles scratched by kids with keys, glint as the train roars out of the gaping maw of a tunnel and sails across the sunny skyline. The sonorous hum of hulking metal bounding along is almost calming; it might lull you into a not-unpleasant sleep. Maybe there’s a trio of men dressed in sailor outfits rhythmically banging sticks against overturned paint buckets, drowning out the idle banter of commuters. Or a woman with an acoustic guitar wailing out the high notes. Or a couple taking up a third seat with their shopping bag despite the pregnant woman standing near them. Or some children hanging from the bars. Maybe there’s a kid with a box of snacks he’s selling for a dollar, or a man sleeping beside his shopping cart with newspapers for a blanket. Books are held with the one-handed dexterity of familiarity as riders lean into the turns and remain admirably upright.

It's all so quotidian, so familiar.

Most of us who have lived in that city will spend what seems like years of our lives commuting, sweating, huddled in a mass of bodies, holding that sweat-slick pole and trying to shrink to take up less space. (“Abomination, thy name is Subway,” Colson Whitehead wrote in The Colossus of New York.) The subway is a phenomenon torn from time; it never changes, even though the city is always in flux, evolving like a massive writhing organism. Yes, trains may look different than they used to, and the fare goes up, and the technology of the turnstiles improves, but the experience remains the same. The subway is sort of poetic, with all the odd sights and sounds. There’s a sense of shared experience, even if we are alone. But that’s the thing about New York: you’re never really alone.

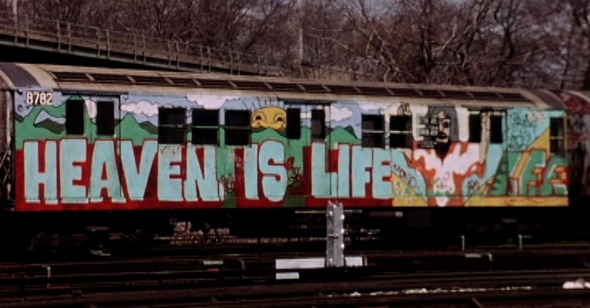

Manny Kirchheimer’s Stations of the Elevated, which was shot in 1977 and premiered at the New York Film Festival in 1981, is a time capsule of tawdry old New York, back when the city was sordid and a little more special. Ed Koch, a man who quipped he would sic wolves on the riff raff to keep the subways safe, had been elected mayor in 1977. Violence was on the rise. The Bronx Zoo was raging at Yankee Stadium, where Reggie Jackson, the straw that stirred the drink, hit three home runs on three straight pitches in the World Series after a season of off-field tumult with on-again off-again manager Billy Martin. Son of Sam was taking his orders from a dog, and Rupert Murdoch had purchased The New York Post, and the New York City Blackout of 1977 led to widespread looting and over $7 million in damage. Kirchheimer may not address any of this—there is no narration at all, just the ambient sounds of the usual city din—but you can feel all these events thrumming in the film, feel the sense of chaos in the cacophonous trains festooned with graffiti, bulbous fonts and enigmatic emblems and cartoonish signatures. Kirchheimer distills the essence of the city into 45 minutes of trains trundling along, piebald in paint; the film is a beguiling sequence of 16mm images that, in their steady accretion—each careful composition giving way to another, complementing and speaking with each other—depict a fugacious moment of the city's long life.

The New York City Subway opened on October 27, 1904. It comprises 248 miles of routes and 665 miles of revenue track. About 40 percent of the tracks are elevated, mostly in Queens and Brooklyn. It’s these elevated trains that capture the imagination of Kirchheimer, who also produced and edited; he shoots the trains lovingly, abstractly, framing shots from behind branches or the architecture of bridges, the tin tubes going 17 miles-per-hour past derelict buildings and steel structures and billboards of women beckoning with voluptuous lips a hundred feet tall. (The old advertisements are among the film’s great pleasures, giant faces staring right at you, whorls of smoke rising from O-shaped mouths.) The wordless film has a lyrical, musicality to it. The rhythmic, incisive editing has an early hip-hop quality, with its sharp rhythm, and the score, courtesy of Charles Mingus and his big band, is a rapturous consort to the concatenation of images, with the band banging away, horn blowers blowing and the drummer beating the skins while Mingus’s bass bops along, pluck pluck. (Mingus spent time living with his aunt in Jamaica, Queens, in the 1960s, so he knew the subway well.)

By the 1970s, ridership was at its lowest since the 1910s, and the MTA was hemorrhaging money. It was a bad time for the MTA, but a good time for street art. There was a glorious profusion of graffiti beautifying the trains, a variegation of colors and shapes, a kind of urban expressionism. “Giant names, elaborate drawings, these beautifully expressive murals—they took my breath away,” Kirchheimer told Rolling Stone in 2014, when the film was enjoying a resurgence after decades in obscurity. (Artists whose work bedizened the trains in the film include Lee63, Phase, and Slave.) Modern graffiti began in earnest in 1955, shortly after the death of sax legend Charlie Parker. Tags reading “Bird Lives” appeared around New York. In the 1970s, New York became a hub for street art, with taggers like TAKI 183 getting attention for their beautiful vandalism. (Varda’s doc Mur murs, also released in 1981, shows how street art was also ubiquitous in L.A.) Graffiti spread beyond Washington Heights and the Bronx and was soon ubiquitous. (One of the trains in Stations reads, “For the People of this City.”) Former mayor John Lindsay declared war on graffiti, but he couldn’t stop the spread. His successor Abraham Beame went as far as establishing a police squad to counter the taggers, which worked, and by the 1980s the subways and facades were clean again. The final tagged train was retired in 1989, ending an epoch.

Graffiti isn’t very common in New York now. The city seems a little emptier, a little uglier without it. Riding the 7 Train into Queens, just across Newtown Creek in Long Island City, you can see a big, bland building once known as 5 Pointz, not far from MoMA PS1. This used to be a bastion for street artists, who were free to beautify the facade with anything they liked. It was an institution, an icon, a place where young artists could show off their craft, and the diversity of styles was astounding—gnarly monsters with long drippy tendrils and plump-faced cherubs and Biggie Smalls with those gazing eyes and comic book characters and perverse smiley faces glaring maliciously. It was beautiful. Then, in 2013, the owner sold it to make condos and overnight they whitewashed all the artworks. “Graffiti is one of the few tools you have if you have almost nothing,” Banksy once said. “And even if you don’t come up with a picture to cure world poverty you can make someone smile while they’re having a piss.”

Kirchheimer’s film lasts for one city day, sunrise to sunset. The gloaming now. Shadows spread as the sun sinks. Saffron bleeds across the sky and streetlights spark to life. The trains retreat to the yard, a nest of slumbering giants.