Reviews

The film is a reflective presentation of how an entire generation was drawn into the digital sphere in response to a physical world that often left them in a despondent state of isolation, dissociation, and dysphoria.

The filmmakers repeatedly return to one notable formal strategy: building up a link between two people across a given scene or shot, then punctuating it by cutting to a heretofore unseen observer.

The title of Vengeance Is Mine, All Others Pay Cash may be slick and playfully edgy, but in ironic passages, Edwin ruptures that tone.

Feathers is a caustic rejoinder to a country still dragging its feet on gender parity, particularly when it comes to the issue of labor.

The film dissects the status of Bangladesh as a postcolonial nation that, like many other postcolonial nations, tries to establish itself as a free nation while holding onto symbols that tie it back to the period it wants to (impossibly) outgrow.

The Balcony Movie is about the contingency of human perspective and what that means for our lives and relationships, but it is also about what thoughtful works of art can create.

The premise/gimmick features Guido Hendrikx behind the camera as he approaches the doorsteps of strangers and stands there waiting for any kind of encounter.

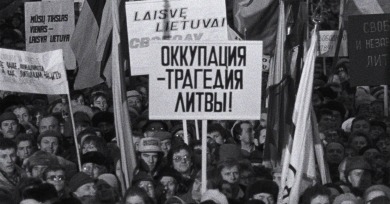

These evidential images provide a midpoint between knowledge and history, and between a subjective and objective truth. This is the framework for Loznitsa’s archival cinema: a kind of foundation on which we can build a better understanding of the world.

With Ahed’s Knee, writer-director Nadav Lapid returns—with a vengeance—to his native Israel after his 2019 detour to Paris with Synonyms, and with its predecessor, Ahed’s Knee shares traces of autobiography.

Muntean depicts well-meaning urban folk who aim to help the country’s rural areas but end up needing rescuing themselves. Muntean’s story is then a social parable disguised as an adventure movie, with undertones of folkish horror.

Over the course of four hours, Loznitsa constructs a granular record of Lithuania’s moves towards independence.

The film, starring Adele Exarchopoulos as a hard-living, pain-numbing flight attendant on a fictional low-cost carrier, is a welcome indictment of the leisure culture and spiritual malaise of the Common Market.

When I’m on the set, I’m learning about what I’m constantly drawn to. Part of it is instinct, and part of it is your own obsession, what you’re drawn to. Once I started making films, without losing that theoretical approach completely, that’s when you start gravitating towards things that move you or that attune you.