Reviews

The film, starring Adele Exarchopoulos as a hard-living, pain-numbing flight attendant on a fictional low-cost carrier, is a welcome indictment of the leisure culture and spiritual malaise of the Common Market.

When I’m on the set, I’m learning about what I’m constantly drawn to. Part of it is instinct, and part of it is your own obsession, what you’re drawn to. Once I started making films, without losing that theoretical approach completely, that’s when you start gravitating towards things that move you or that attune you.

Great Freedom confirms Rogowski as a protean and exceptionally physical performer, a screen star who appears to emit his own force field.

The film is a richly layered look at the conflicting longings and impulses of early adulthood, the cinematic equivalent to a bittersweet love song that also happens to be catchy as hell.

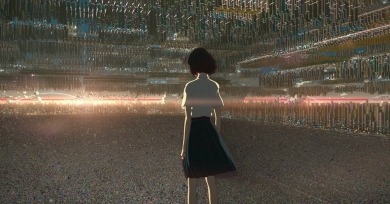

His penchant for fantastic narratives has caused many to liken Hosoda to Miyazaki, but work hews closer to the heightened melodrama of his contemporaries in anime like Makoto Shinkai and Naoko Yamada. His tenderness and perpetual optimism are key to why Belle and his other films are as beautifully drawn as they are.

Licorice Pizza conveys summertime dreaminess with very little of the lassitude that usually comes with it. Sun-drenched teen suburbia never moved so fast; everyone is always running toward or away from something, whether cops, coke-crusted movie producers, restaurants, or pinball palaces.

Resurrections is born from a different era; its text is concerned with the matters of trans people who have lived openly as themselves long enough to have actualized those desires and develop new fears.

As with Uncle Boonmee and Cemetery of Splendour, Apichatpong often materializes traumas in the form of phantoms that hover in the margins of his protagonists’ imaginations, visiting and sometimes haunting them in the same way the present is always shaped by the ghosts of the pasts.

Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth is full of lovely, obvious, expressionistic style choices, which not only registered on my limited Shakespeare palate but felt invigorating after 18 months of watching mediocrely lensed historical dramas on my TV.

Gyllenhaal is more muted on the suggestions of queerness in the book, leaving them burrowed in undertones and bringing her preoccupations with motherhood and womanhood to the fore.

The older film is often classified as a noir (even though it is lacking some of the tropes and visual signifiers of that pseudo-genre), which del Toro has taken as an excuse to stuff his version with constant cigarette smoking and monsoon-like rainfall in his usual literal and immoderate fashion.

The film is brave, generous, and vulnerable about how often and how long queer people have to negotiate with concepts of childhood and home, and how they carry the loaded, weighted sense of dread, painful memories, and regret among their families.

Dumont presupposes Seydoux’s purpose: she cries, we feel. But tears are tricky things, and like the central problem of news and entertainment, we are never sure if her sorrow is true or false.