Michael Koresky

Like Father, Like Son has the unfortunate effect of making Kore-eda’s greatest attribute as a filmmaker—his sensitivity—into a liability.

Spielberg’s most naturalistic, emotionally penetrating work was made in the 1980s with cinematographer Allen Daviau, who shoots with a devotional warmth rarely seen in films as scrupulously designed as Spielberg’s.

Theirs is admittedly not an open-arms type of filmmaking, but no one could accuse Inside Llewyn Davis, at once their warmest and most fragile film, of treating its complicated, imperfect protagonist with disdain.

A Few Great Pumpkins

The Tenant; Burn, Witch, Burn; Tourist Trap; Trilogy of Terror; Ganja and Hess; Dead of Night; The Blair Witch Project

If nothing else, Bruno Dumont’s Camille Claudel 1915 proves that a movie star really is a completely different animal than the rest of us schlubs.

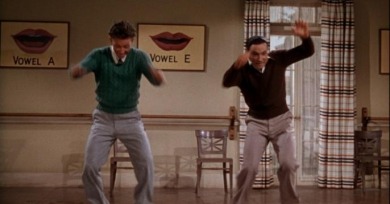

For a film so widely beloved, Singin’ in the Rain is truly mischievous, the ultimate expression of a genre that is more about spirit than cause-and-effect narrative relations.

Passion thrillingly, and humorously, recontextualizes De Palma’s regard for trash by reveling instead in a new kind of junk, the stuff of high-end consumerism.

Old Cats is crammed with the stuff of life—not just the roiling emotions that take up space in its characters’ heads, like regret, anger, neuroses, and occasional joy, but also the literal things that pile up in their houses: books, computers, medicines, and, most of all, tchotchkes.

Young filmmakers and critics alike speak of the American seventies cinema with a grandiose nostalgia, as though everywhere one turned there was another masterpiece just waiting to be picked, like a fresh-cheeked apple from an endless orchard.

When Allen has dared to venture into darker psychological portraiture (a.k.a, when he’s “gone serious” in films like Interiors and September), he’s risked displeasing viewers who’d rather cozy to the relatably anxious than the genuinely depressed or dysfunctional.

There’s no strict design to the film: one gets the sense that there could have been an infinite number of other versions of Chungking Express—with just a slight turn, the camera may have alighted on a different lonely soul and begun an entirely new story.

Rarely has something so lofty felt so leaden as Pedro Almodóvar’s latest, a comedy that mostly takes place aboard an intercontinental flight, stuck circling over the ground because of a landing-gear malfunction.

Sergei Loznitsa’s In the Fog is stimulating viewing for those among us still on the lookout for auteurs of serious moral and aesthetic intent.

Before Midnight is the first of Richard Linklater’s films charting the ever-expanding romance of Celine (Julie Delpy) and Jesse (Ethan Hawke) that hints at a silence between the lines.

Why is it an important time? Because it’s now. And we’re here. For our tenth-anniversary symposium, then, we want to stand in numbers against the gloom-and-doomers.

We envisioned our publication as a product of a particular culture—that of the “film-as-art journal,” which we knew only as specifically the domain of print—one we might have known was dying around us if only we’d checked our impetuous enthusiasm long enough to pay attention.

To the Wonder is filled with the sorts of mysteries that not only make Malick’s work indefinably captivating but also instill awe and hope for the future of a medium supposedly in its death throes.

Carruth has claimed to be “weirded out by synopses,” and this is in keeping with his film, which feels terrified to parcel out information in any sort of way that might be given the dreaded label “conventional.”

There’s no evidence that Korine is aiming for irony with Spring Breakers—contemporary, media-driven culture is so self-reflexive that it’s hard to tell the difference between earnestness and satire anymore. That ambiguity of meaning fuels Korine’s film.

In the U.S., Reality might be too easy a sell. Have you ever watched the teary, mascara-stained faces on The Bachelor and mused about the possibility that these allegedly lovelorn contestants were somehow less than genuine?