Jeff Reichert

To make the idea of a national cinema compelling, audiences need a body in which to locate the quirks and idiosyncrasies of that nation’s filmmaking—services that Ingmar Bergman, Abbas Kiarostami, and Akira Kurosawa each performed in their time.

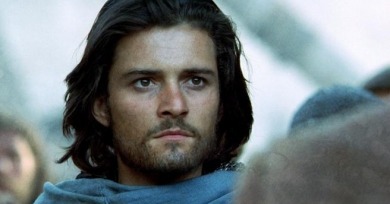

No one does pompous like Ridley Scott. Where a film of average self-importance might look down its nose at an audience from time to time, a Ridley Scott vehicle does so while conducting massed woodwinds and coordinating a rain of individually picked rose petals from the heavens.

"There are many levels of meaning in all my movies, but I don’t think that there is a level that is nobler or wiser than another. If one wants to look at film as pure entertainment and chooses to merely enjoy the nice lighting—it’s perfect for that. But if others want to dig, they can go deeper. But they won’t be more right. They’ll just be deeper."

When it's said that an artist-filmmaker, painter, poet, performer-“defines a generation,” it can either refer to his attempts to reflect on the behavior of his times on his canvas, or it can be mere fortunate happenstance.

"When I can use one shot, I won't use a second one. But if you look closely, I often move the camera slightly, often when I'm following the characters. It does have to do with my theater training-there you don't have a camera and are dealing with real space and time issues which I've tried to carry over into my filmmaking."

I'd imagine Tsai bemused and more than a little bit flattered at the time and verbiage critics have spent dissecting these “two sentence films” in the service of elevating him to the forefront of ranks of world cinema's auteurs.

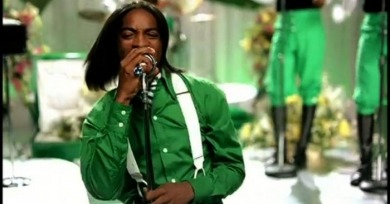

But what are musical numbers good for if not to allow characters to express those things the narrative cannot contain? In retrospect, Tsai’s characters seem like they’ve all just been waiting for someone to strike up the band.

If the recent events at the nefarious Republican National Convention taught us anything, it should be obvious that in the current American mentality direct address is more crucial than art-world acceptance.

Though we’re probably not alone in this, America is too adept at forgetting the inconvenient, awkward, or shameful moments of its past, even when there’s so much to gain through simple, unadulterated remembrance. It’s the lesson of In the American Grain and a large part of Snow Falling’s power as well.

Leigh takes his examination of the “back alley” abortion a step further, replacing the commonly imagined horrors surrounding the practice (see a recent example in the dreadfully overwrought The Crime of Father Amaro) with something closer to warmth, even love.

The Village seems acutely aware of the relationship between filmmaking and mythmaking, an inquiry all too welcome in the face of society’s current desire to dead-end culture into the morass of reality television.

"I never liked school that much, I never fit into any kind of academic program. I never liked official systems of any kind. Without even thinking about it, I just realized that wasn’t the place for me. I saw it as a long-term process, my filmmaking. I knew it would be a long time coming and I didn’t want to be humiliated right off the bat."

If there exists one piece of solid proof that aging gracefully is still a possibility in an era of sequels, prequels, and remakes, it’s Richard Linklater’s Before Sunset.

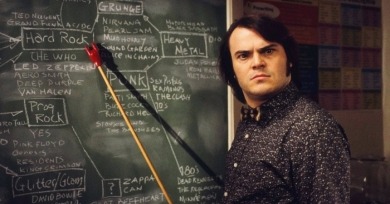

Instead of taking the easy road to reaction shots, the camera’s gaze is perhaps more than a little puzzled, but ultimately completely endeared of its subject, ridiculous as his compendium of rock star moves and clichés may render him.

What is it that the cinephile searches hopefully for on the screen if not some glimpse of perfection, the face of some god?

Forgive me Mel, but The Passion of the Christ just plain stinks. To be expected, I suppose—did anyone really believe that Mad Max was capable of a cinema that operated beyond the kind of plodding, dunderheaded ridiculousness that makes The Passion little more than a prequel to Braveheart?

Is it parody, pastiche, or homage? Can there ever be another Fred Astaire or Gene Kelly? Most interestingly, is it possible any longer to make a musical without the text making reference to itself as such?

If there’s a contemporary director’s filmography that cries out more for the inclusion of a musical than Tsai Ming-liang’s, I’m not aware of it.

R.E.M., “Bad Day”; OutKast, “Hey Ya”; The White Stripes, “I Just Don’t Know What to Do With Myself”; Britney Spears (w/Madonna), “Me Against the Music”; Liz Phair, “Why Can’t I?” Stars, “Elevator Love Song”; No Doubt, “It’s My Life”; The Strokes, “12:51"; Bubba Sparxxx “Deliverance”

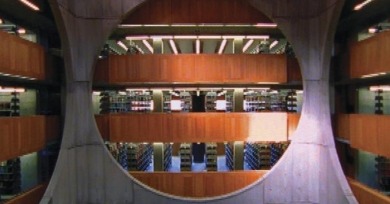

I can only stand so much awkwardly delivered voiceover about making peace with a barely known father figure before growing a little skeptical of a documentary’s motivation, especially when said figure is a luminary on the level of Louis Kahn.