Jeff Reichert

The outsized critical gangbang which met the release of M. Night Shyamalan’s Lady in the Water bespeaks of a community of writers gripped by the worst form of pile-on groupthink imaginable.

Take One inaugurates an ongoing series of symposiums in which our writers will tackle the whole of a film through some fundamental piece of cinematic construction: an edit, musical cue, color, and so on.

In a cinema so obsessed with the idea and integrity of the shot, singling out this one instance for examination is a gesture worthy of Solomon.

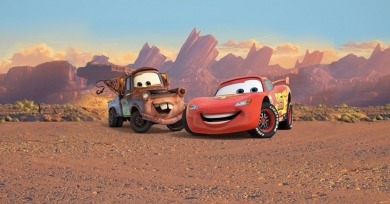

With John Lasseter and Joe Ranft’s Cars, the ever-growing commercial imperatives required to feed the beast that is Pixar have overwhelmed any sense of responsibility towards their audience.

When critics bring the word “shocking” to bear, what is it that they’re really saying about themselves and how they view their audience?

Since Paul Greengrass decided to make a crude, mechanistic schematic out of the events of 9/11 and the crash of United 93 rather than a full-bodied film with some small shred of humanity, it seemed most appropriate to build a response around a list rather than a complete review.

The ability to shock on various levels, is an obviously powerful tool, and if a filmmaker could somehow consistently find his or her way to that magic point for a mass of viewers, the work would approach a particularly dangerous and effective space.

What to say in the face of Terrence Malick’s The New World? What to say indeed in the face of a film that has left me at turns wobbly-kneed and energetic, teary-eyed and grinning, melancholy, and ecstatic?

I value these moves greatly because a filmed version of Jane Austen featuring an attractive cast of fresh faces and reliable codgers propping up a hot young ingénue needn’t choose to do any of them to find an audience.

We’re No Angels represents the first flowering of solid sense-of-place craftsmanship which would help ground works like The Butcher Boy and The End of the Affair, where the mode of discourse perhaps rests closer to Beckett’s Not I on a relative scale.

Marked by oblique, carefully composed frames, a general lack of camera movement, an aura of hipster cool, and a flirtation with genre, Danny Boy seems at first like a cross-Atlantic cousin to Stranger Than Paradise.

The grubby, shaky-cam technique used in hot-topic features bearing the documentary tag these days betrays the ignorance of their makers—these folks may have important stories to tell, but that in no way frees them to indulge in substandard filmmaking.

You don’t often find mainstream critics admitting that they haven’t seen The Godfather or Bicycle Thieves or King Kong or Vertigo, but in all surety, they’re out there.

Plain and simple, for better and for worse, The Godfather represents the best of what commercial American Cinema has the ability to accomplish.

Jarmusch has widely been cited as a “minimalist,” an easy, often ill-used tag for someone who is much more interested in the big picture. His films luxuriate in set pieces, just perhaps not on an imposingly grand scale.

As genially foulmouthed as one would expect, given a collaboration with the writer and star of Bad Santa, Bad News Bears is about as charmingly unchallenging a film I’ve seen in ’05, which may sound like faint praise coming from a serious critical journal like the one you’re currently reading.

The idea of doing an issue entitled East Meets West began as an excuse to write about our favorite new East Asian filmmakers, that batch of preternaturally gifted artists who have been flowing out of that “other” corner of the globe for the past decade.

To make the idea of a national cinema compelling, audiences need a body in which to locate the quirks and idiosyncrasies of that nation’s filmmaking—services that Ingmar Bergman, Abbas Kiarostami, and Akira Kurosawa each performed in their time.

No one does pompous like Ridley Scott. Where a film of average self-importance might look down its nose at an audience from time to time, a Ridley Scott vehicle does so while conducting massed woodwinds and coordinating a rain of individually picked rose petals from the heavens.

"There are many levels of meaning in all my movies, but I don’t think that there is a level that is nobler or wiser than another. If one wants to look at film as pure entertainment and chooses to merely enjoy the nice lighting—it’s perfect for that. But if others want to dig, they can go deeper. But they won’t be more right. They’ll just be deeper."