CineVardaUtopia

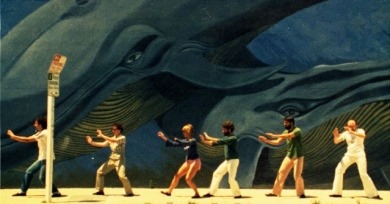

If any single quality defines the paintings scattered throughout her films, it is their refusal to exist simply as beautiful objects, and their ability to allude to profound timelessness, lifelessness, and stillness.

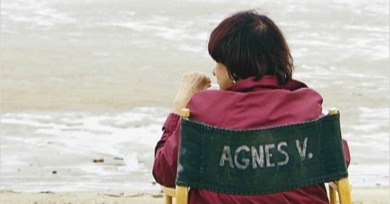

Her continued relevance should come as no surprise as the realm of work that Varda has spent the past 60-plus years exploring—a multifaceted intersection between narrative and documentary—is becoming ever more in vogue.

“I was filming this postcard, and my camera went [to my hand], and I thought instead of saying my hands are old with spots, I said, it’s a beautiful landscape. And in a way, it’s a way of being a filmmaker that my own age becomes a landscape.”

Appreciated from a perspective of sixteen years, the film now seems to fit perfectly in the moment of its making, but still feels as fresh, original, and full of optimism as it used to be when it was first released.

One Hundred and One Nights, all soft edges and winsomeness, is a nice little movie, maddeningly so. The cinema has written enough love letters to itself; it could use more anonymous threats, bricks through its window, and flaming turds on its porch.

Jacquot de Nantes depicts the young Jacques Demy as both furiously precocious and fundamentally innocent, devouring the magic, myths, and mechanics of cinema.

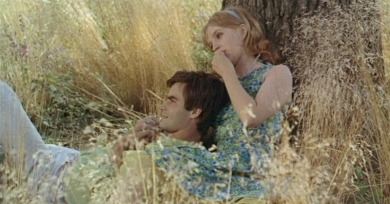

What drives her captivation with Julien? Based on a story suggested by Birkin herself, the screenplay by Varda offers a multitude of answers, each inchoate and interconnected.

Jane B. par Agnes V. is an elliptical film, and, like other Varda films (La Pointe Courte, Jacquot de Nantes), the line between the fictive and the real is deliberately porous.

Though hearing about the death of a man from exposure to the elements provided Varda an initial spark, it soon turned into a story of the specific snares of a female vagabond experience, and by extension the female experience.

Adrift and alienated, yet invigorated by what she had discovered, Varda felt an immediate kinship with the underrepresented populace of Los Angeles. Channeling these conflicting feelings, Varda would produce a pair of features.

One Sings may ultimately be gentle in its politics, but Varda could probably never make a truly mainstream film: her artistry is too exquisitely singular, too intrigued by moments out of time and the unspoken words between people that can only be expressed through abstraction.

Even in the context of a body of work that more or less exemplifies the concept of personal cinema, Daguerreotypes is as close to a self-portrait as you can get without being one.

Lions Love is a staged documentary about a performance of events and ideas and attitudes that were very real to 1968. It could hardly matter less whether or not the film was good, or worked in any traditional sense.

The Creatures makes sense primarily as a kind of bitter, exaggerated parody. In its vision of male-female relations, it comes off as a grotesque embellishment of the French science-fiction movies it followed and a warning to the ones it preceded.

Varda makes one wonder about the ways in which platitudes can be both aimed at selfish ends and deeply felt all at once.

Though Varda already was a highly experienced photographer and thus no stranger to the art of image-making, her lack of cinephile knowledge at this early period in her life helps make La Pointe Courte not only authentically personal but also singular.

She is very charming, very vain, and very blonde. She is also a woman in a moment of internal crisis, awaiting a diagnosis from her doctor regarding the tumor in her belly.

In selecting the subject of our latest director symposium, we alighted upon a figure of constant surprise, of reinvention, of charm and oddity and intellectual freedom. She is one of the most thrillingly alive filmmakers working today, and she is 88.