Off the Walls

Jordan Cronk on Mur Murs and Documenteur

More than most cities, Los Angeles is a place of myriad contrasting identities. Depending on one’s perspective, the city may be synonymous with Hollywood, the music or television industries, one of a handful of professional sports teams, or the cult of celebrity nurtured by these same commercial enterprises. But even taken together, these guises tell only a partial story (and a privileged one at that) of Los Angeles’s rich history. As with most metropolises, it’s when one looks to the margins of society that the city’s true lifeblood is revealed. Ironically, it often takes an outsider to highlight and properly account for these everyday virtues.

Following a stint on the United States’ West Coast in the late 1960s, when she produced a pair of short documentaries in and around San Francisco, followed by the 1969 feature Lions Love (...and Lies) in the hills of Hollywood, Agnès Varda, recently separated from her husband, director Jacques Demy, retreated back to Los Angeles at the dawn of the eighties in search of personal and creative fortification. What she found differed greatly from the enclave of privileged hippie artistes so memorably documented in Lions Love; a counterculture of a different kind had instead asserted its presence amidst a city in the throes of redevelopment. Drawn away from the hills and toward the margins of the city, Varda discovered a thriving culture of working-class minorities and creative types operating as diverse, autonomous entities in the shadow of Los Angeles’s capitalist facade. Adrift and alienated, yet invigorated by what she had discovered, Varda felt an immediate kinship with this underrepresented populace. Channeling these conflicting feelings, Varda would produce a pair of features, Mur Murs and Documenteur, two very different yet inextricably linked films made in quick succession in 1980 and 1981.

Though you wouldn’t know it from most Hollywood films and television programs, one of Los Angeles’s most recognizable features is its vast expanse of public murals. The history of street art in Los Angeles dates back to the early 1900s. In his foreword to Street Gallery: Guide to Over 1000 Los Angeles Murals, former Cultural Affairs Department General Manager Adolfo V. Nodal writes that it was a Scandinavian immigrant by the name of Einar Petersen who first turned a number of downtown locations into sites for large-scale paintings. But it wasn’t until the seventies, when the city of Los Angeles began to fund public murals, that the phenomena took off county-wide, emboldening the dispossessed. Robin J. Dunitz, author of Street Gallery, goes on to note that the majority of the city’s murals were created after 1968, the same year Varda began production on Lions Love and one year prior to her return to France. By 1980, Los Angeles was a living monument to itself, the city’s cultural heritage writ large across its vast topography. And yet the visibility of this art form and its rich history in mainstream media is at best low, and at worst nonexistent.

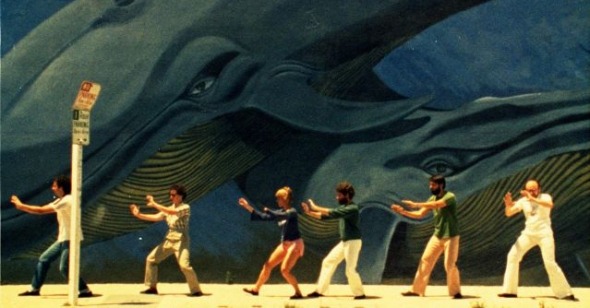

Varda set out to document this unique movement with Mur Murs, a loving portrait of Los Angeles told through the art and artists that so rarely receive recognition for shaping the city’s diverse sociological and geographic complexion. At once observational and inquisitive, the film interweaves wordless passages that soak in the murals’ grand scale and minute details with interviews of both the artists and a selection of civilians who offer their thoughts on the art and utility of public murals. The artists, largely of Chicano and African American descent, speak passionately of the history and cultural necessity of their art; with little representation in popular entertainment, these murals have become de facto illustrations of entire lineages of Los Angeles’s multiethnic bedrock. Often depicting key figures or culturally specific traditions, the murals simultaneously reflect the city’s vibrant civic constitution and the ephemeral essence of their own materiality within a constantly evolving municipal landscape. In a telling early example, Varda notes in voiceover how the top half of the Life in Venice mural was demolished so undercover police officers could monitor drug activity in the surrounding area, leaving visible only the legs of its African American subjects.

As well as being a thorough document of the city’s public art scene, Mur Murs doubles as a guided tour (one led intermittently by actress Juliet Berto) through many of Los Angeles’s less storied regions. The film begins in Venice Beach, with its multiracial populace and generally inclusive atmosphere (in Varda’s words, “a mix between Fire Island and Greenwich Village”), but soon expands eastward into Compton and Gardena, Vernon and Monterey Park, downtown and Boyle Heights, neighborhoods removed from the epicenter of Hollywood and comprised of largely minority communities living self-sufficiently. It’s here where we meet the artists responsible for many of the city’s most celebrated murals: the feminist Chicana artist Judith Francisca Baca tells of her successful initiative to enlist a group of students and local gang members to paint a 1500-foot mural across the Tujunga Wash river basin to sketch an alternate history of Los Angeles by re-contextualizing familiar iconography (of Charlie Chaplin, The Lone Ranger, and Lassie, among others) through an ethno-historic lens; the late Charles Felix walks us around Estrada Courts in Boyle Heights, site of over 55 murals chronicling Chicano antiquity; while self-described “public image-maker” Richard Wyatt Jr. remains soft-spoken as his craft is extolled by both Varda and the principal of Compton’s Willowbrook Junior High School, the halls of which are adorned with the former student’s artwork.

More than Varda’s unassuming formal command and sly narrative intuition, it’s the sociohistoric integrity of the activities and personalities depicted that lend the film continued relevance. Some of the murals featured in the film survive to this day; many do not. Some, like Les Grimes and Arno Jordan’s decades-long project “Hog Heaven,” which wraps around the Farmer John pork-packing facility in Vernon, retain enough intrinsic interest to receive the appropriate upkeep. Others, like those imagined by the Asco arts collective, whose “living murals” made a virtue of site-specific application and volatile material constituents, were never designed to last. Considering the confluence of artistic activity and community support, Varda’s timing was no doubt serendipitous. But Mur Murs is no mere curatorial coup. As ever, the director’s penchant for creative diversions (such as an interlude on tattoos and car art) and ear for the rhythms of urban life (multiple sequences pause to simply absorb the sounds and music of the streets) add to the textural richness of a work with no shortage of visual pleasures at its disposal. It’s such an infectious, idyllic vision that it’s startling to think that something several times more sobering could be conjured from the same wellspring of experience.

At a glance Documenteur bears little in common with its predecessor. With its melancholy tone, subdued color palette, and generally methodical pace, it’s just about the stylistic inverse of Mur Murs. In fact, save for rhyming opening and closing shots of the same utopian mural, there aren’t many surface similarities between the films at all. But this fictionalized narrative concerning a divorced mother and her young son living modestly in the west side of Los Angeles is defined by a similarly itinerant sense of place, and as such strikes a more personal chord than any of Varda’s California films. Billed as “An Emotion Picture,” the film stars Sabine Mamou (editor of Mur Murs) as Emilie, and Mathieu Demy (Varda’s real life son) as Martin, whose transient existences have rendered them indistinguishable amidst an overcast, unforgiving landscape.

The Los Angeles of Documenteur is a sterile simulacra of Mur Murs’ vibrant, sun-drenched expanses, with community and camaraderie replaced by isolation, introspection, and addiction: sequences of documentary-like intimacy, of seemingly real people and predicaments, emerge from the drama only to fold quietly and without comment back into the narrative. Navigating this dreary setting with understandable stoicism, Emilie and Martin gather discarded furniture as they search for a more permanent residence away from the beach house they temporarily call home. Though she’s clearly a surrogate for Varda, not much is revealed about Emilie, whose clerical job at a film company offers little artistic fulfillment (at one point she’s asked to record the voiceover for a film that we soon gather from her reading is actually Mur Murs), while her sex life amounts to unenthusiastic trysts with her neighbor. “Why don’t you laugh more often?” Martin asks his mother late the film. “Sometimes I forget,” she responds, capturing in a brief exchange the loneliness that haunts even the liveliest environments.

In his 2003 essay film Los Angeles Plays Itself, Thom Andersen differentiates between what he terms “low-tourist” and “high-tourist” filmmakers. Low-tourists, he contends, “generally disdain Los Angeles,” citing, among other things, their preference for more picturesque upstate locales, while the best high-tourist directors of yore “weren’t interested in what made Los Angeles like a city; they were interested in what made Los Angeles unlike the cities they knew.” On evidence of Mur Murs and Documenteur, Varda is something of a quintessential high-tourist director (coincidentally, Andersen singles out Demy’s Model Shop, made during the couple’s first sojourn in Los Angeles, as an exemplary high-tourist film). She’s drawn not to the city’s most recognizable locations and landmarks, but to both the fringes and the underbelly of an otherwise homogenous municipality. Varda saw in Los Angeles what many residents take for granted (or, in the case of the city’s more alienating qualities, refuse to acknowledge), and with insatiable curiosity and empathy sought to document the lives and experiences of those—whether natives or newcomers—ill-served by the city’s bureaucratic infrastructure. At once unmoored and undeterred, she emerged heroically with two of the most honest and illuminating films about Los Angeles ever made.