Take Two: In the Cut

Where before we offered our writers the shots of their choice, here we gave them not only two shots, but the space in-between as well.

It doesn’t take long to realize that we aren’t watching a scene in Michael Haneke’s Code Unknown but from something tentatively called “The Collector,” a movie within Haneke’s movie.

For years this single cut has held in my mind as a rebuttal to all of the expensive blockbusters that rely on costly explosions, explicit crashes or elaborate computer-generated effects to get a rise from the viewer, when something as simple as a perfectly placed jump cut can startle just as effectively.

The first few minutes of Days of Being Wild (credits for executive producers, cold opening, title card) are my favorite few minutes in a movie made in my lifetime.

Stripped of any traits of her former character, d’Orsay’s face becomes enshrined as love goddess solely through the logic-defying action of the cut; the viewer is thrust up against a contextless image purporting to entice their deepest carnal yearnings by sheer virtue of its assertive presence.

To understand a film by Anger is to understand the use of sound in accordance to the cut. It is to learn from a master.

What’s so striking about the Bressonian universe, and probably most responsible for his lasting reputation, are his editing decisions; it’s rare that a shot ends exactly when you might expect it to, and even rarer that what follows provides easy linear causality.

What grounds Soderbergh’s pop pastiche, I think, is that a revenge thriller is basically about a character’s desire for historical correction—an honor killing that rewrites the record. For the director, of course, that’s also a matter of carving up his influences.

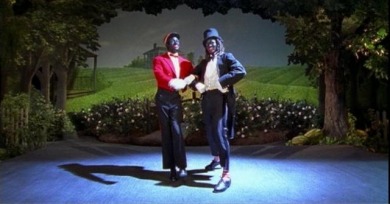

With Bamboozled, Spike Lee entered the new millennium and announced, without the slightest hesitation, that filmmaking was still a primitive medium. Technologically and educationally unformed—made suspect and misshapen by those who wielded it, and barely ready to be vindicated.

Instead of a gunfight, the final duel is one of competing visual systems—the classical Hollywood hero and icon of conservativism taken down by a school photo signifying the brutality of an America plagued by gun violence.

For years, I have isolated one surreptitious shot match in her largely overlooked Nenette and Boni as defining her particular brand of brilliance, which merges hyperstylized formalism with gentle realism to create something at once tactile and relaxed.

Rope can be seen as a denial of the edit, a kind of negation or repudiation of its importance and power. At the same time, the presence of the cut despite its elision, its status as “not there but there,” could be seen as the definitive test and proof of the very centrality Rope seems to deny.

From one scene’s end to another’s beginning: standard cutting practice... Except that the two shots are separated by something: a title card, bold white on black, stating bluntly: “MEANWHILE.”

Andrei Tarkovksy’s The Mirror is full of such event-cuts, each defining or sensing the cohesive whole of the film, like its maker, as discrete moments hung together through time, however disparate and dispersed its instances, like his limbs, may seem.

There’s a cut late in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ that does more than connect, surprise, or demonstrate: it quakes and shifts the ground below.

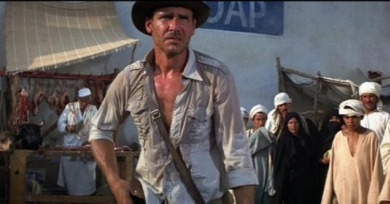

What gives the sequence its memorable charge is Indy’s bemused reaction shot—an interruption to the sword-twirling antics that announce spectacular danger, but don’t black out his practicality.

Like so much of the film, this cut makes literal what in the novel is philosophical, and some ideas made material are worse for the wear.

When one thinks about Alan J. Pakula’s 1970s conspiracy trilogy—Klute, The Parallax View, and All the President’s Men—the first thing that comes to mind is Gordon Willis’s superb visual work.