Sidelong Glance

Travis Mackenzie Hoover on Nenette and Boni

Those who know me know that I will use any and all excuses to write about Claire Denis. However, this one-cut symposium provides me with a more specific justification: to write about the greatest cut in the Denis canon, if not cinema itself. For years, I have isolated one surreptitious shot match in her largely overlooked Nenette and Boni as defining her particular brand of brilliance, which merges hyperstylized formalism with gentle realism to create something at once tactile and relaxed. Now it can be told: a single cut related to classical film grammar while also expanding and redefining its emotional range, it places the director astride the line of cinematic convention.

The set-up is quite simple. Boni (Gregoire Colin) is an 18-year-old school dropout with a sexual fixation on a baker’s buxom wife (Valeria Bruni-Tedeschi). For much of the film he has vented his domineering fantasies in diary and monologue form, most of them involving bringing her to her knees in some literal or figurative sense. The baker’s wife—a gentle, emotionally generous sort—is completely unaware of this, knowing Boni simply as a customer and treating him with kindness. Story tension has been created by Boni’s pursuit of this erotic target, but Denis doesn’t satisfy it with a standard pass/fail of sexual victory or rejection. Instead, she sets them up to meet under casual circumstances and offers a nebulous redefinition of their relationship.

The cut occurs shortly after Boni and the object of his desire have met by chance in a shopping center. They sit down to talk, and after one shot of Boni looking off-camera at the object of the desire, we cut to the first shot in question as the Baker’s Wife settles into her seat. The impressive thing about the scene is the length at which we observe the Wife as she talks:

Baker’s Wife: I like it here. (pause while she takes off her jacket) I never have any time. It’s nice to meet someone from the neighborhood. What’s your name?

Boni: Boniface.

Baker’s Wife: Now I’ll know. (takes drag from cigarette; suddenly reaches out her hand) Smell this! (Boni smells) What does it remind you of?

Boni: I don’t know.

Even in these bits of random dialogue, the camera stays glued to the Baker’s Wife. Boni’s head pops from off-camera to hold and smell her wrist, but he’s incomplete; we’re pretty much trapped in Boni’s point of view as the oblivious woman explains her request:

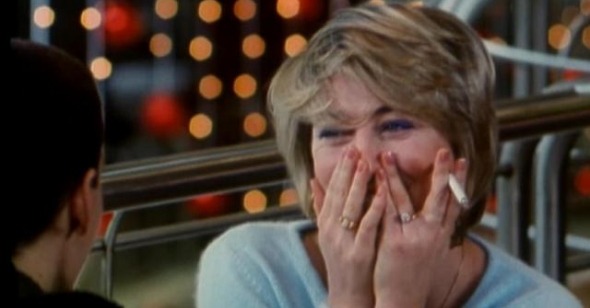

Baker’s Wife: Just skin. I barely use any perfume since I read the article. I’m afraid I’ll cover up that famous molecule—pheromone, something like that. (pause) There’s a chemical reaction between men and women. These invisible things set off signals… they say things like, “You turn me on” and “I’m available.” It’s crazy. They’re in everything—in truffles, in oysters, in beer, in flowers, in other things too. (pause) There’s even a molecule like it—not the same one, but almost—that works on animals and female pigs, when they get sprayed with it. (starts laughing) It drives them crazy!

The shot is a documentary of mannerisms and interruptions: we fixate on the way she flips her hair when she laughs, the way she smokes, the pregnant pauses as she collects her train of thought. Though the shot is devoted to her, it’s a voyeur’s gaze. She doesn’t know Boni’s designs or that he is looking at her as we are, collecting details of her physicality, watching how she does things when she isn’t paying attention. As she discusses the science of attraction, we are caught up in its more immediate sense—while she is completely unaware of the idea.

But as we watch her entirely innocent performance, Boni must also become aware of the gulf between them. He/we may snatch erotics from the gaze, but they aren’t being freely given: the lead-up to this moment has prepared us for more than this can allow, and so we are trapped in the space between what Boni can take from the encounter and what he would like to take.

Thus we are simultaneously aroused and disappointed when we cut to the reverse shot of Boni in his chair while the Baker’s Wife natters on:

Baker’s Wife: But it’s totally unfair. Some people have tons of these molecules, and others have almost none. So you can pour perfume all over yourself, but it won’t do a thing. You’re out of luck. They’re like invisible fluids. See what I mean? They’re like…

Boni has been staring impassively ahead as she says this, but as she trails off there is a silence, and he smiles as if understanding something for the first time. He’s seen the gulf between fantasy and reality: his sex object has been made human, and thus further from his erotic grasp than ever. And he’s been surprised by the encounter, by the details filled in by the person that is inseparable from the body.

What does this mean as a cut? In one sense, it encompasses the same kind of visual information as the most lazy of editing practices, the shot/reverse shot. Boni and the Baker’s Wife are seated across from each other, and what little cutting there is in the scene doesn’t budge from the facing-forward setups: one could easily see a lesser director interspersing her dialogue with clips of Boni just to liven up the rhythm and let us know that he is part of the conversation. But Denis takes this most common of setups and, through a lack of action montage, manages to inject meaning.

The result is a most unusual piece of subject positioning. By holding on the Wife, we are no longer cutting the scene into brief informational units: we are left to consider the infinitude of gestures that she executes and assimilate them into the film’s ultimate meaning. But by cutting back briefly to Boni and his moment of clarity, we’re also aware that we’ve been watching from his point of view. The approach has consequences on our identification: though we’re clearly looking through the hero’s eyes, we are not engaging in a conquering gaze that decides for us what to look at. Boni’s position of narrative superiority is at once bolstered and challenged by the total commitment to the Wife’s face and dialogue. We are aware of his point of view, but just as aware that he is not the master of all he surveys.

This fact is further established by the dialogue’s drifting over into the second shot. Standard shot/reverse shot practice is to establish a point/counterpoint that makes the two speakers equal—if it doesn’t exactly give the characters one shot for one line, it still divvies up their talk into more or less discrete units. But the Wife is allowed to keep going with her inadvertently erotic monologue even as we are returned to look at Boni— and once again, we are returned to both the source of the gaze and its powerlessness. The Wife is clearly oblivious to both the provocative nature of her talk and the lust in the heart of her companion—and the talk that wafts over the line of the cut establishes both that the wife doesn’t know what’s going on and that Boni’s desire for mastery isn’t going to be satisfied.

The talk only trails off in the final moment—allowing Boni to collect himself and register, with that silent smile, his understanding of what’s occurred. The scene ends there; it’s barely noticeable in a film full of such slippery moments that are gone before they can fully register. But it epitomizes for me Denis’s artistry, which takes a perfectly conventional pair of set-ups and turns them into something mysterious, telling and contrapuntal. And it points towards the infinite possibilities within the most accepted cinematic practice when given the opportunity to rearrange its individual components.