Intervention

Eric Hynes on The Last Temptation of Christ

In cinema, pictures pass by so quickly, with such small fractions of difference between them, that the eye perceives motion. Then new pictures appear that are contextually different in some way, the transition to which presents a break, a visible dislocation that is the grammatical basis of the art of film. Breaks and edits aren’t exclusive to film, but that instant cleaving of two distinct moments to create imaginary time—human intervention that hazards shape and a suggestion of meaning—is. Beyond the dictates of convention, there’s no knowing when the cut will come, how it will come, if it will come, what its coming will mean. It’s a prevailing power that films and filmmakers have over us—there’s no flipping ahead or checking the program. And some cuts go deeper than others. There’s a cut late in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ that does more than connect, surprise, or demonstrate: it quakes and shifts the ground below. The entire film anticipates this cut, as do we, because of our expectations of the climax to the greatest—or, at least, most repeated—story ever told, but still there’s no preparing for it. Image yields to image, and the very concept of Christ—son of God, son of man—achieves an articulation more potent than in two thousand years of adamant theology.

An alchemic convention of industry and the ineffable, Gilberto Perez called film (in his invaluable book of the same title) “The Material Ghost.” In Midnight Movies, Jonathan Rosenbaum and J. Hoberman likened the movie theater to a modern church, a communal space of reverent rapture where a shaft of light conquers darkness and transports the soul. For Scorsese, as a child equably ardent for Catholic and cinematic transposition (he famously studied for the seminary), his mature commitment to the latter has always brought the weight—both explicit and implicit—of the former. His conflation of faith and cinema makes him optimally suited for a truly cinematic approach to spiritual text. After weaving conflicts of faith into Who’s That Knocking at My Door, Mean Streets, and Taxi Driver, with The Last Temptation of Christ Scorsese finally enfolded medium and message; flickered film was spirit in both word and deed.

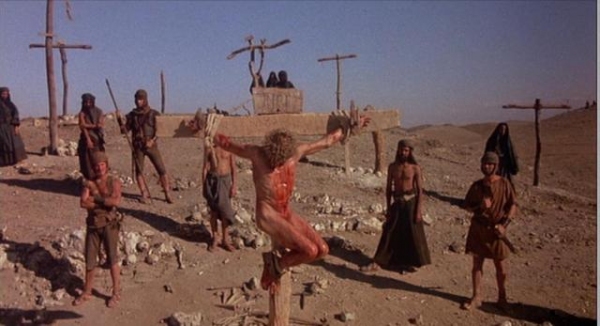

Yet form and subject are audaciously matched. Pointedly employing the full arsenal of film grammar and drawing from the whole expanse of film history, Scorsese restores Christianity’s diffuse, often unrecognizable remnants to their origin. Though ostensibly set and dressed with fidelity to Christ’s time and place (true to the Nikos Kazantzakis source novel), the language employed is a frankly stylized pastiche of the twentieth-century cinematic. At first off-putting, the clash of cadences and referents develops its own harmony, a rhyme of trickled-down tropes and themes retuned. Judas Iscariot is a pink-haired Harvey Keitel, bullish and method-acting sincere, a refashion of his conflicted street thugs of Scorsese films past, but also evoking, depending on the moment, Edward G. Robinson’s similarly ill-fitting turn in The Ten Commandments, Brando in On the Waterfront, and the dons of The Godfather films. When Jesus (a volcanic Willem Dafoe) betrays his betrayal, Judas thunders, “You broke my heart,” sounding out both vowels in “heart” like a defeated dockworker. The references are bare and copious, and when contemplated, wholly appropriate. The Judas character informed those artifacts, and Keitel’s Judas absorbs them back. His characterization suggests centuries of cultural history, yet is always instinctively human. There are snapshots of Pasolini and Tarkovsky, of Kubrick and De Palma, Jodorowsky, Jarman, Antonioni, Ford, Fellini, and Coppola, likely dozens of others only the director himself could cop to. Scorsese empties the bag. When Jesus raises the dead, we’re led to think of zombies. Walking the desert he’s a western hero. When he offers his blood at the Last Supper, vampiric disciples sup. It’s film as postmodern origin story—Christ’s, Scorsese’s, and ours. And like the infuriating conundrum of Christianity itself, the seeming impossibility of such a trinity is what fascinates.

Opening with a slanted tracking descent out of Tarkovsky’s Ivan’s Childhood and closing with an emulsive transcendence reminiscent of Bergman’s Persona, Scorsese traces Jesus’s life from conflicted soul to spectacular abstraction. When, in its final act, the narrative fully breaks free of the gospel story, Scorsese reaches for Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, itself an Americana spin on Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. But here all is inverted. When the road not taken is taken, there’s no telling where it will lead. Therein lies the cut.

Though spiritually and emotionally titanic, the cut is a simple and narratively familiar one, where identical—or basically similar—shots bookend a tangential sequence that necessarily alters either the meaning or the impression of the returned-to shot. It’s a filmic boomerang and literary—and frankly real-life—truism: that our impressions of people and places are modified by the intervention of time and distance. Since film’s physical allure depends on confused perception, it’s appropriate that this tangent is often expressed as a dream, a time out of time that nevertheless slants waking reality. And since film itself is innately dreamlike, dreams depicted have a narrative power little diminished in relation to depicted reality; in fact, they are truer to form.

Such is the case with Last Temptation, which perhaps helps explain why the film offended believers when it opened in theaters in 1988 (outside of knee-jerk, sight-unseen, holier-than-though prohibitionist hysteria). The power of film to actualize and legitimize the dream-state allows for, in Scorsese’s adaptation, a third act that is more truly blasphemous than the notorious novel upon which it is based. But it’s also, thanks to Scorsese’s conviction in the expressive potential of his medium, a more compelling expression of true faith.

As originally conceived by Greek author Kazantzakis, the dream is Jesus’s own. At the eleventh hour, a guardian angel appears at the foot of the cross and relieves of him his mortal burden. He resumes life, no longer God but fully man, and proceeds to marry, procreate, and grow old. On his deathbed, visited by his aged disciples, a scorned Judas scolds him for abandoning the cross and mistaking Satan for his guardian angel. Jesus realizes his error, overcomes his last temptation, and is restored to the cross.

In the novel the passage is unmistakably dreamlike, his departure and return to the cross a flighty, out-of-body remove from an otherwise earthy approximation of reality. The filmed adaptation begins somewhat dreamily, with a gentle cessation of sound and the sudden appearance of a precocious young girl who claims to be an angel. But his deposition is a grounded, physical one, with the angel pulling out nails from his hands and feet, and he’s shown walking past his tormenters and further and further away from the cross. There are signifiers of dream, but the ensuing scenes don’t depart too drastically from the entire film’s stylized mise-en-scène. Which is to say, Jesus’s desirous dream is blasphemous enough, but Scorsese’s film goes further, visually realizing, with narrative accumulation, Christ’s departure from the sanctity of the cross for the banality and carnality of normal life. The transition is demarcated, but one image still follows the next, one neither replacing nor negating another but moving forward and further, each accumulating in time. Our perception has a way of collapsing image and time, so that context eventually matters less than the impact of a given instance—in this instance, the unshakable sight of Jesus Christ French-kissing a prostitute.

Where It’s a Wonderful Life posits a world in which George Bailey had never been born, Last Temptation posits a world in which Jesus had never died on the cross. They lead in opposite directions, but both end in exhilaration: one celebrating the power of a single life, the other celebrating the power of a single death. Jesus’s life as man evokes George Bailey’s restoration, and it’s hard to begrudge him his beaming bride and bouncing children, his adoring Zsu Zsu and guardian angel. The dream—his temptation—looks an awful lot like an affirmation. He wants this, and blasphemy be damned, we want it for him. What’s the world missing if it all turns out as idyllic as this? Acknowledging the potential irrelevance of the actual crucifixion, Kazantzakis and Scorsese conjure preacher-man Paul (Harry Dean Stanton!) spreading Christ’s story regardless of its literal truth. He’s undaunted by the sight of the living Jesus, because he knows that a story compellingly told—the son of God made the ultimate sacrifice on a cross to cleanse us from our sins—is more potent than the truth, more potent than actual sacrifice. It makes Jesus’s defiance of this last temptation less about the future and the formation of church—Paul’s got that covered with or without him—or even about the saving of the world. It’s about a man’s conscience. He wants his life to mean something, even if it means death. He wants to provide meaning to words and concepts, to literalize sacrifice and legitimize story.

Confronted by Judas, fooled by Satan, made irrelevant by Paul’s opportunism, Jesus hastily rolls from his death-bed and crawls atop a hill. The burning of Jerusalem backlit behind him and klieg lights a-flaming his prostrate form, he confesses his final sin. A flip of Gethsemane’s doubts, he now pleads to be taken back, for God to let him proceed with the divine plan. He wants to die and forsake the life of men. To forsake desire, pleasure, happiness, contentment. To give back what his reverie led him to believe he’d just taken. His posture, his concision, is another latter-day restoration: it’s Christian conversion enacted by Christ himself. His words are not those of Kazantzakis, and resemble not Scorsese’s Catholicism, but the contrite Calvinism of screenwriter Paul Schrader. Arms outstretched, he asks for forgiveness, and with a sudden swollen sound (of music? of an airplane engine?) we cut back to Jesus on the cross. Cutting to motion, the camera pulls in quickly (where it earlier slowly pulled away) and rests, chest-up, on Dafoe’s gnarled form. God/Scorsese has intervened—and given the story meaning. He’s back where he was, but everything has changed. The cut restores Christ, but stirs us. He’s returned to the cross, but where he just was is fresh in our minds. His sacrifice is made tangible. There’s a shape to it, an arc of life that shadows his death.

The perverse liberties of Last Temptation’s extra-gospel narrative almost obscure the greater perversion, which is the desire for Jesus’s restoration—the Good Friday celebration of an unspeakably painful death. But Scorsese, again going further than the novel, nods to the paradox and muddies the triumph. Committed to visceral, emotional ambiguity to the last, he restores Jesus to the height of his humiliation and pain, now confident where before he’d been fearful, divinely committed since being tempted. Yet the wallop of his conviction frightens as it conquers. Lip quivering, eyes clear of sin yet demonically expressive, Dafoe’s Jesus is exorcised but suddenly raptured, remote and no longer human. Son of man has flipped to Son of God, and he’s not coming back—not in this film at least. As his last words attest, uttered first in full-throated pride and then in an agonized whisper—it is accomplished, and it’s both strangely beautiful and scary as hell. Welcome to the big break, the new era, A.D. as seen from both ends.

Then there’s a cut of nearly equal importance, even as the camera remains fixed on Christ. Scorsese transitions from the fading noise of the cacophonous crowd to highly pitched, warbled alien/angelic/demonic voices, an invasion from some other world. If the sudden, spliced native singing of Peter Gabriel’s recording is the sound of heaven, it’s as terrifying as the look on Dafoe’s ecstatically expired face. When bells start ringing—a comparatively comforting sound—the picture appears to disintegrate with flickered light, visible sprockets, and an Exploding Plastic Inevitable rainbow-psychedelia show. Within the minute, Scorsese has expressed Christ’s becoming as a single swift cut, and now he finds filmic equivalents to the remainder of the trinity—the frightful call of omnipotence and the intricate, unknowable brilliance of the spirit. It’s like a Brakhage composition: Scorsese’s spirit is a zeroing of form and content. It is conviction made material.