Features

Years in Review

No Home Movie, Toni Erdmann, Cemetery of Splendor, Cameraperson, Aquarius, Moonlight, Right Now Wrong Then/Sunset Song (tie), Silence, Certain Women/Knight of Cups (tie), The Illinois Parables

The casual, festive atmosphere of the FicValdivia Festival, located at the small university town on the banks of Valdivia River in Chile is fueled by its largely young programmers and audience.

A Few Great Pumpkins

La Jetée, I Walked with a Zombie, Creepy, Jacob's Ladder, Young Sherlock Holmes, Vampyr, The Pit and the Pendulum

Just as Jay takes his place as the figurehead of a pagan cult, so too did Kill List crown Wheatley as the king of UK horror movies when it was released theatrically, a speedy ascension to a throne that had sat vacant since the 1970s.

Lots of huge, multimillion-dollar video games look very impressive from the dominant but qualitative perspective of judging digital visuals by how much they don’t look digital at all.

Includes Mimosas, The Death of Louis XIV, Personal Shopper, Elle.

This year’s Competition features a number of burgeoning talents as well as notable critical darlings, resulting in an uncommonly stimulating first week. On Sieranevada, Staying Vertical, Toni Erdmann, Slack Bay, Paterson.

Far Cry 2 perpetuates and depends on colonial themes and values as much as any open-world game, with the key caveat that it works a critique (or, at least, a cynicism) of the colonialist project into its playing.

The Berlinale takes great pride in promoting itself as the most politically conscious and engaged of the A-list film festivals. After the events of the past year in Europe, refugees were the salient topic of its latest edition.

There is no narration, no translation, and no explanation for the dense thicket of ritual gestures that we are peering into, each of which, one can intuit, has behind it an entire system of symbolic meanings.

What if we could see what is actually on the other side of the world from where we sit? . . . Russian documentary filmmaker Victor Kossakovsky approaches these questions with a mixture of the digging child’s ingenuousness and the dogged explorer’s rigor and sense of purpose.

In Herzog’s 53-minute documentary on the Gulf War and its aftermath, the war begins and ends by the fourth minute.

Herzog rarely misses a chance to leap on canoes, wade through sludge, and handle native arrows. When he faces the camera and bares his zeal and fears, one glimpses a man capable of directing as well as starring in Moby Dick.

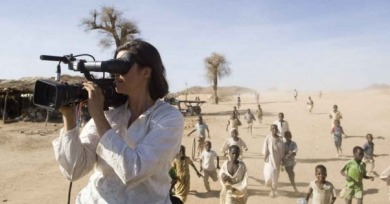

The camera is weapon and savior, mediator and patient observer, but it is never objective in Cameraperson, an extraordinary and singular filmmaking document by Kirsten Johnson that quietly lorded over everything I saw at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival.