Map Man

An Interview with Toponymy director Jonathan Perel

by Michael Pattison

Toponymy played Sunday, January 17 at Museum of the Moving Image as part of First Look 2016.

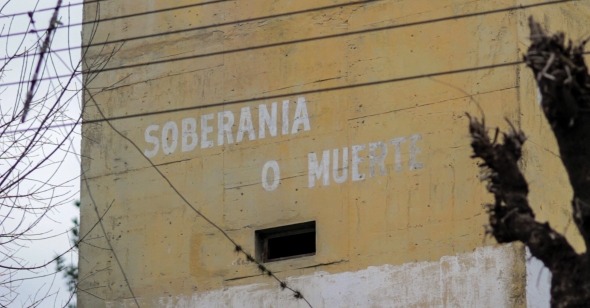

Toponymy, the study of place names, is a fitting title for Argentine filmmaker Jonathan Perel’s new work, his first feature. Both abstract and precise, the term implies a scientific inquiry, a historical investigation, a fascination for truths that aren’t always or immediately obvious. Perel’s Toponymy is an exceptional landscape film that traces the foundation and arrangement of four small towns in the remote hills of Argentina’s Tucumán province. It was here, in the 1970s, where the country’s armed forces initiated Operation Independence, a counterrevolutionary campaign disingenuously referred to in official documents as a “rural relocation plan.” Though the operation’s ostensible objective was to centralize the local populations, its primary purpose was to annihilate the leftwing guerilla movement that had previously found the region’s terrain so tactically advantageous. The four towns resulting from this so-called resettlement scheme still bear the military names by which they were first inaugurated.

In Toponymy—which receives its U.S. premiere at Museum of the Moving Image’s First Look Festival on January 17—Perel dedicates a narration-free chapter to each town, each of which uses 58 tripod-fixed compositions lasting fifteen seconds to map its unique layout. As we proceed through the minutiae, however, our perception of the gestalt transforms: though the towns were constructed in disparate locales, the blueprints that open each chapter reveal their near-identical design. Perel structures his chapters accordingly: the first shot of each sequence directly references that of others, while all the second shots also refer to one another—as do the third shots, the fourth shots, and so on. It’s an ingeniously simple concept that nevertheless prompts a complex and active viewing process. I spoke to the filmmaker at last year’s Viennale, where I saw the film for a second time. We spoke about cartography, the film’s structure, and its hauntingly ambiguous coda.

Reverse Shot: Toponymy is a very geographically specific film. How well known is the history of this region to Argentineans as a whole?

Jonathan Perel: It’s almost not known, even in very deep circles of academic investigation. The strange thing is that these towns are in the middle of the jungle, twenty or thirty kilometers from the main road, so it’s even hard for nearby towns to know these places. I read about them in an academic article about people who had disappeared in Tucumán. It was only a footnote in the article, about four towns with military names. I started looking on the Internet, and there were almost no pictures. When there is no information on the Internet, it’s a good subject for a film.

RS: We see from the blueprints for the towns how the military imposed a kind of grid-like rigidity onto this pre-existing space. How quickly did the idea of structuring your film like this form?

JP: Since I found that the design of the towns were actually the same, it was very clear to me that I should just shoot the same shots in every town. I had a previous film, 17 Monuments [2012], about monuments that were built in the entrance of former concentration camps in Argentina. In that film I shot each monument with exactly the same lens and distance, and at exactly the same time of day. This idea of minimalism and repetition was very clear, so when I found out about these towns it suited me perfectly from the beginning. It was a slow, very delicate process to get inside the towns, because only 300 or 400 people are living there. If they don’t like you at the beginning, that’s it, you have to leave. In small towns it can be hard. “What’s this guy doing with a camera, shooting our houses?”

RS: So you show up to each town as a one-man crew, with a tripod and a camera?

JP: It’s a one man-crew. No sound guy, no producer. I show up in a rented car, which is strange enough, and tell their delegate what I am doing. I know how to put the camera on a tripod and speak with people because eventually they like that you’re shooting. It’s not that they don’t like it. But it was slow. First, taking pictures, then shooting. It took me a week, in each town. I would come one day, return two days after, at different times of the day. I knew the towns were exactly the same—I had the blueprints and the maps—but I didn’t know exactly what to shoot. Let’s say I go to the first town. I shoot the entrance. I shoot every street. I shoot every house. But then I find this strange umbrella form in the plaza, and I’m not sure what it is. Maybe I don’t shoot it. But when I go to the second town, I find the same strange umbrella, and I say, “Oh, this is a repetition. I have to shoot it. I have to go back to the other town to shoot it.” This went on for a month, finding new places maybe in the third town. Or the other way: finding places in the first and the second but not in the third. This astronomic clock, for example: “Where is the astronomic clock?”

RS: It sounds a little chaotic. At one point did you begin to conceptualize it with more mathematical precision?

JP: I made these lists of what I found, like an Excel chart with columns and colors, saying, “I need to shoot this, this, this and this.” Maybe I saw this but I didn’t shoot it. Maybe I have to go back to reshoot it because of the lighting, or whatever. All the time I was checking the material that I’d shot and making notes and going back to the places. That’s something I’ve done in all of my films, to approach ideas or things to shoot that I am certain I can shoot for long periods of time—come back and reshoot. I re-shoot a lot, because I don’t like the light or the framing. I made one film [Tabula Rasa] where they were demolishing a building in a former concentration camp, and it was very hard for me to shoot it because I couldn’t go back another day and shoot again. I prefer things like [Toponymy].

RS: The film’s structure is quite teasing. There are no dissolves or no superimpositions and the correlating shots are kept separate from one another. It’s not immediately obvious what it all means.

JP: It’s something I found out early in the editing. The obvious decision would be to show the entrance to the first town, then the entrance to the second town, to just point out the similarity right away. But I felt it was unfair to treat the audience like that. It’s like giving them an opportunity—I will give you one chapter, and when the second chapter starts you will do your work and remember the same beginning. Maybe it’s not easy in the second one. It becomes easier in the third chapter and even easier in the fourth. At the end the structure is very clear. But I think it would have been a very obvious film had it been the same shot, one after the other.

RS: And the shots are always the same length?

JP: They are always the same. All the shots in my films are always the same, but they are different from one film to the other. In this film I didn’t want it to be too long. They are about fifteen seconds. It’s the minimum. I cannot make this film with shots of less than fifteen seconds. A difficult editorial decision was to make all the chapters the same length, because when you’ve already seen the first chapter you don’t need as long for the second chapter. Maybe it can be shorter, and the third one even shorter, because you already know the framings. But that’s also betraying my audience. Maybe you need even more time, because you’re comparing the shot to the one before. So maybe it should have been longer.

RS: It’s almost as if each image draws you in, and just as its meaning is beginning to register we cut to the next image. It’s like a violent rupture, and a large part of this, I think, has to do with sound. You don’t use sound bridges. The cuts can be quite harsh.

JP: I don’t like those kinds of manipulations. It’s more like a cartographic work, or a film map. I don’t manipulate the sound itself, but I manipulate the levels. Sometimes I decided on the fifteen seconds you see because of the sound, basically.

RS: There’s a discrepancy between how obviously different the blueprints are from one another and how identical the towns look at street-level.

JP: When you’re at ground level it becomes more difficult to see that they are not all exactly the same. The only question here was whether or not to shoot from above the tower. You need an aerial shot to really see the differences. I could only access one tower so it didn’t make any sense [to include a shot from there]. I was very lucky with the documents. They were in the cartographic office of the capital city of Tucumán.

RS: I sense here a personal fascination with cartography and architecture. What draws you to maps and blueprints?

JP: I love every kind of drawing or device that you can use to describe reality in an abstract but at the same time more precise way. When I like a building, I look for the blueprints to really understand it. I can understand a building better by seeing a two-dimensional vista instead of a perspective. I like these objective forms of explaining reality.

RS: In addition to its four chapters, Toponymy also has an epilogue filmed in the jungle, which goes unexplained.

JP: I like explaining it. At the beginning, I wanted this project to be half in the towns and the other half in the jungle. Many people have told me it could have ended without the epilogue. For me it’s very important. I go back to the very few ruins that I found, of the former towns that were destroyed to move the people into these towns. What I found is maybe just a little house, or some stones in the ground. You don’t know where to fix your eye because it’s the jungle, as opposed to the rest of the film where it’s very clear: you’re looking at a monument, or very precise objects in the center of frame. This idea of not knowing where to look in an image is very important in political terms. It’s the space of the revolution, where the guerilla members chose to hide from the military, to create an armed force and take over the government. It was a place of freedom, so I needed to finish the film there. If not, it’s a film that the military could have made, in [proudly] showing what they did.

Image courtesy of Jonathan Perel.