Martin Scorsese: He Is Cinema

For such an icon, Scorsese is fairly tricky to pin down. What threads, if any, connect his various, distinctive films? Is he more fascinating a director because of commonalities between his films or divergences?

The Wolf of Wall Street is perhaps the most despicable, entertaining, and despicably entertaining film we’ve yet seen from Scorsese, plunging headlong into the excess surrounding Belfort’s meteoric, hedonistic rise and pillow-soft landing.

The death of cinema has been heralded countless times over the past several decades, suggesting that we are well into its ghostly afterlife. Martin Scorsese’s Hugo surveys cinema from this postcinematic station, returning to the profound connection between childhood wonder and early cinema.

Martin Scorsese had a terrific time during the production of Public Speaking, his portrait of writer and New York mainstay Fran Lebowitz. I know this not from anecdotal evidence or first-hand experience of the shoot, but from what’s on display in the film itself.

The unnerving inside-out quality of Shutter Island’s psychological portrait draws from and builds on Scorsese’s beloved film noir tradition to a point of abstracting the genre, with its exaggerated visual motifs and fragmented subjectivity.

In Scorsese’s movies, the main character is time and again faced with the dilemma, “Why am I what I say I am?” These men go forth to prove their souls without any guarantee. This is not necessarily a matter of deception or even self-deception.

The Aviator’s first act is so intensely experiential and bizarrely fast that it feels like we’re watching a civilization in freefall, a three-ring circus with Hughes as its reluctant master of ceremonies.

The film opened fifteen months and nine furious days after September 11, 2001, when there was still a gaping wound in the ground, when regardless of whatever could be done “to build this city up again,” it was “mightily” and irrevocably changed.

The film remains an outlier, ignored by programmers of two recent Scorsese retrospectives in New York and the public alike. Clearly, Bringing Out the Dead does not need to be rescued from oblivion; it needs to be resuscitated. Let's start by calling it a comedy.

The lush golds and crimsons, the dreamlike dissolves and dollies, the transporting drone of Philip Glass’s score. From our vantage, it seems less a curveball now than a natural entry in one of the most eclectic filmographies in American cinema.

Goodfellas is a nervy blast—nostalgia-soaked, endlessly quotable, and oddly fun even as it grinds toward a tragic drug-addled end. Casino, both chillier and more hothouse by turns, nauseatingly violent and deeply, woefully sad, is no one’s idea of a good time.

The Age of Innocence is as brutal a film as anything in Scorsese’s filmography—and it is also just as kinetic. His camera is constantly in motion, insinuating itself between characters, panning, tilting, and tracking from faces to walls to plates of food to silverware to fine china.

Other critics have looked at the psychopath Cady (a role De Niro lobbied hard for) as an extension of Travis Bickle or Rupert Pupkin, but this rather misses the point. It is Nolte's Bowden who is the “Scorsese male” here (Cape Fear's own Henry Hill, or Jordan Belfort).

Scorsese’s twelfth and greatest feature, adapted from Wiseguy, a mob-tell all narrated by stoolie Henry Hill to novelist Nicholas Pileggi, casts a long, enveloping shadow over the past twenty-five years’ worth of studio, independent, and television productions from the U.S. and elsewhere.

The many raging bulls of Scorsese’s career tend to be overgrown, mewling children, from multiple De Niros to Pesci’s trigger-happy Tommy DeVito and Nicky Santoro—art-world star Dobie, although a more articulate, sellable buck, fits right in with these men, banging at the bars on their cribs.

Opening with a slanted tracking descent out of Tarkovsky’s Ivan’s Childhood and closing with an emulsive transcendence reminiscent of Bergman’s Persona, Scorsese traces Jesus’s life from conflicted soul to spectacular abstraction.

From Who’s That Knocking at My Door to The King of Comedy, Scorsese’s is a cinema of losers—of stunted men whose sad fates, though they might elicit our sympathy, do not qualify as tragedy because they had nothing of greatness in them to begin with . . . The Color of Money, conversely, is about winners.

As with all of Amazing Stories’ other directors-for-hire, he did not have final cut. And though he enlisted his own screenwriter, After Hours’ Joseph Minion, to work on the teleplay, the episode, as with the majority of Amazing Stories installments, was based on an original story by Spielberg.

The more he tries to move forward, the less progress he makes; likewise, the more the viewer tries to make sense of this nightmarish world of uncanny repetition, the less clarity one gets.

The phrase ahead of its time is a problematic one, as it is premised on the idea that any given time has a single defining attribute. Applied to The King of Comedy it’s even trickier—have we really caught up with Scorsese and De Niro’s film?

Raging Bull has the oddest grandness. Of all those agreed-upon Great American Movies, Martin Scorsese’s sort-of-biopic about fighter Jake LaMotta is surely among the most conceptually strange and discomfiting to experience.

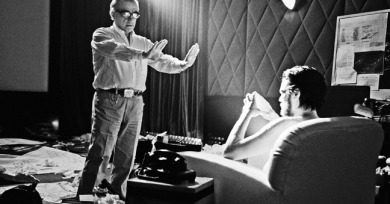

Scorsese’s film actually incorporates and subverts more than one documentary convention at the same time: the interview, the archival fragment, the confession, the staged reenactment, the raw behind-the-scenes glimpse.

The multiple cameras grant the viewer a privileged access to the stage from every possible angle except the perspective of the audience. This creates a filmic space in which we are united with those who create the music, yet are separated from those who listen to it.

It’s worth wondering, since the protagonists of certain musicals seem to share Jimmy’s dream of establishing this perfect balance, whether the musical, too, is somewhat allergic to the idea of marriage as a sustained habit of life rather than as a grand romantic finale.

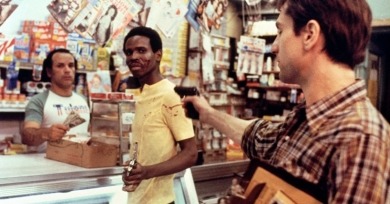

In order to amplify Bickle’s tortured psyche and intimate his prejudices without verbalizing them, Scorsese consistently traffics in images of black males as hostile beings, perhaps in part to put his own spin on the urban landscape routinely depicted in the blaxploitation films of the early 1970s.

Female experience is a fraught and contradictory thing in Alice, established within a matrix of domestic responsibilities, culturally influenced fantasies, and conflicting social expectations regarding the proper relationship between a woman’s desires and duties.

In its almost bratty simplicity it shows up so many contemporary nonfiction films, which often seem to exist only to document the exemplary or the culturally notable, and in their slavish obsession with their subjects’ import end up squelching the kind of resonance that Italianamerican casually exudes.

It was the instinctive, holistically integrated flourishes of Mean Streets that would construct a working model for much of Scorsese’s future output.

Knocking, filmed on weekends over the course of three years and subject to reshoots and name changes throughout, was conceived as the beginning of a never-completed trilogy about Scorsese’s coming of age in Little Italy.

Marginalized within her own story, Bertha nevertheless takes up a large amount of screen time, but Scorsese seems at a loss as to what to do with her. And her blankness creates a hole in the film.

Many of the qualities we associate with promising student filmmakers—voraciousness, audacity, experimental flair—are qualities we continue to associate with the septuagenarian director of The Wolf of Wall Street.