Reverse Shot for President

If the recent events at the nefarious Republican National Convention taught us anything, it should be obvious that in the current American mentality direct address is more crucial than art-world acceptance.

Like the original colonial settlers, the villagers fall into the same traps they sought to escape: governmental control, religious hypocrisy, contemporary violence.

It says a lot about the state of the world that any country holding up a mirror to itself will invariably find the American specter looming over its shoulder.

Where better to turn for a little contemporary understanding of America than a film that presents 1850s Oregon with all the Technicolor pomp and lumberjack circumstance of an overblown 1950s musical?

Those that turned out to see The Right Stuff, ostensibly compelled by the sexless civics come-on, must have been very confused. Movies like this—an ambitious hybrid, a long, true-to-life space oddity—just weren’t made anymore.

It gives us unique access to American public and private spaces alike as they peddle their sacred wares to housewives in rollers, nervously chain-smoking cigarettes and wondering how they will be able to afford the enormous $40 volume before them, complete with full-color illustrations of the stations of the cross.

Though we’re probably not alone in this, America is too adept at forgetting the inconvenient, awkward, or shameful moments of its past, even when there’s so much to gain through simple, unadulterated remembrance. It’s the lesson of In the American Grain and a large part of Snow Falling’s power as well.

For Fassbinder, the entire logic and movement of late capitalism is irredeemably corrupt. Society is structured so that the only role for the individual is conformity, death, or madness.

The polemicist who is never afraid to turn to populism and sophistry in order to make an argument is also, it’s easy to forget, a preacher reaching for your heart rather than your mind.

Open Range brings a much-needed dose of nuance to a genre whose clichés have grown increasingly stale under Bush’s watch. Open Range doesn’t just revisit the old clichés, it relives them in Proustian detail.

The power of myth is that it ably removes individual initiative from the equation. What seems (and is) crude, flimsy, and base on the plane of the individual becomes omnipresent and impenetrable when lowered to that of the mass.

We’re in the highly radicalized, politicized, and deeply angry world of British filmmaker Peter Watkins, probably the greatest filmmaker that you’ve never heard of. Watkins’s Punishment Park is his deepest incursion into the American psyche, and the centrality of violence in American political and social life.

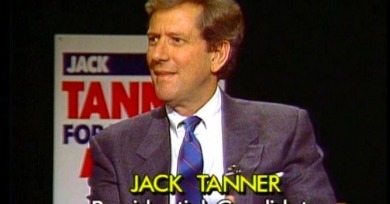

Utilizing his signature roaming camera style, Altman makes us believe we’re watching the drama of Tanner’s run unfold before us unawares. Nothing’s sacred in a campaign and thus every salacious moment is perfectly caught by this anonymous camera.

The spirit that once defined American independent cinema is not dead. It lives in the few artists we have left, still committing images that matter, to a medium desperately in need of heroes.

It is difficult to view David Fincher’s 1999 polemic Fight Club and not recall the 9/11 attacks—in the final shot, two financial towers explode and collapse as Edward Norton and Helena Bonham Carter look on from a vantage point earlier dubbed “Ground Zero” by Brad Pitt.

Harold & Kumar features likable minority protagonists with fully developed, stereotype-defying, well rounded personalities and is also an enormously silly film, ultimately a series of juvenile set pieces selected for their ability to keep the audience giggling through sheer quantity over originality.