Once More in Oh-Four

Karen Wilson on Tanner ’88

On the campaign trail for the Democratic presidential nomination, two old political colleagues run into each other at a small town photo opportunity. Pausing in front of the cameras, one introduces the other to his daughter and all three chat amiably, though they represent different parties. The Democrat mugs that he hopes it comes down in the end to a contest between the two of them. Chuckling, the Republican shakes his hand and wishes him well.

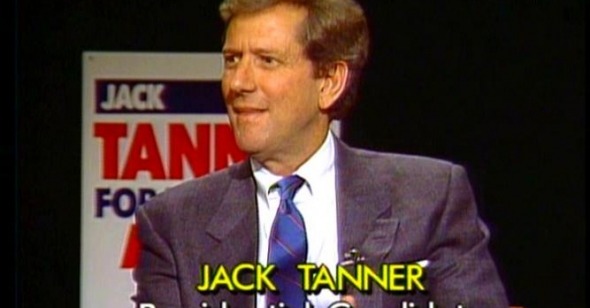

For anyone who lived through the 1996 election or who has caught a few advertisements for Pepsi or Viagra, the face of the Republican—former presidential nominee Bob Dole—is a familiar one. However, the Democrat and his daughter may be less recognizable. They’re actually actors: Michael Murphy plays Jack Tanner, a congressman from Michigan running for the Democrat presidential nomination and Cynthia Nixon as his college-aged daughter, Alex Tanner, who has left school to help her father’s campaign. As the subjects of director Robert Altman and cartoonist Garry Trudeau’s TV political satire Tanner ’88, Murphy and Nixon, plus their staff and the journalists following them on the nomination trail are supposed to blend in with the crowd, looking perfectly natural when at a fundraiser, leading an impromptu student rally, or schmoozing the delegates on the floor of the Atlanta Democrat Convention. Utilizing his signature roaming camera style, Altman makes us believe we’re watching the drama of Tanner’s run unfold before us unawares. Nothing’s sacred in a campaign and thus every salacious moment is perfectly caught by this anonymous camera.

However, unlike most professional politicians who seem as comfortable within their carefully crafted public personas as inside an expensive suit, Murphy’s Tanner has to undergo the transformation from idealistic professor/congressman to jaded spin doctor finagling votes from delegates before Altman’s intrusive camera. We get to see every awkward grimace and flash of self-aware embarrassment on Murphy’s face.

Tanner ’88 runs for eleven episodes—an hour-long pilot plus ten half-hour installments from the New Hampshire primary through the Atlanta national convention. Altman intended for the show, made for HBO, to run through the November election, but it was unfortunately canceled before he could complete it. Thus, the closing moment of episode eleven just after the nominating convention, feels only like a pause, as though the previous vignettes had been just snapshots within a larger picture. The miniseries format and the unresolved nature of the “ending” (will Tanner run as an Independent candidate after losing the primary?), both serve very well Altman’s purpose in constructing a complex satire grounded in “reality.” It’s as though Tanner’s life could not be contained in a two-hour feature film.

Most political films and television shows exist within a vacuum, a fantasy world not reflecting those actually in office but the ideal of what writers and directors wish could be our national destiny. David Edelstein in his Aug 18, 2000 Slate article about political filmmaking, “Pols On Film,” illustrates a cunning narrative trope common in campaign drama that he calls “the Big Speech.” At the climactic moment, our candidate throws aside his carefully crafted words to give his audience, and us, the real deal. It’s meant to be a humanizing and hero-making gesture that tugs at our heartstrings. In Tanner ’88 Altman blatantly eschews this kind of sentiment-grubbing in favor of something more complex. With every episode, as Tanner and his crew confront logistical disasters (a broken-down bus filled with reporters), media bumbling (a helicopter swoops in on the congressman’s wedding), or situations fraught with moral grey areas (the discovery by a reporter of the candidate’s relationship with a fellow campaign’s manager), there do not seem to be any easy answers. This is much more satisfying than any triumphant Mr. Smith Goes to Washington–style filibuster. As the moderator for the presidential debate, Linda Ellerbee (another politico playing herself), points out, anyone who goes through the whole process and gets to the White House probably isn’t someone you want there. Yet Tanner argues, in a direct address to the camera filmed for the Sundance Channel re-release, that this system is the best we’ve got. Altman and Trudeau’s main purpose could be to explicate this conundrum.

Recalling my own memories of the 1988 election, I so remember wanting the process to be reducible to a fight between the good guys and the bad. In our elementary-school mock election, situated as it was in a moderately affluent suburb of San Francisco, it was unsurprisingly a decision for Dukakis by a landslide. In my own house, the Dems were the good guys and Ronald Reagan was “a turkey,” so of course that’s how the whole country must feel, right? Or at least, that was my eleven-year-old reasoning. I remember vividly how shocked I was by the muckraking and badgering about Dukakis’s personal life, in particular the exposure of his wife Kitty’s drinking addiction. For years, I would eye the opaque plastic bottle of rubbing alcohol in our medicine cabinet with wariness and think of our would-be First Lady.

It is intriguing to watch Tanner ’88 16 years later and to be so aware of these hindsight-is-20/20 details about the actual candidates, and particularly to know how it all turned out. Watching Kitty onscreen as herself, in her faux regal posturing, chatting with the actress who plays Tanner’s love interest, is a little cringe-worthy. Yet, it’s still easy even now to be caught up in the characters’ tide of idealism and hope for that year’s election. Like our own current race, there’s a tendency to make it into a Manichean case of good versus evil—a regime that must be removed by a moral (read: liberal) imperative. Yet Tanner ’88 also struggles hard against that tendency. Tanner characterizes himself to the media surrounding him as an aging hippie intellectual whose stance on drugs (legalize them) is based on his own experiences as a spouse of a drug addict. He also is quick to broadcast his involvement in the Civil Rights movement, acting shocked when the flacks around him don’t get his references to Selma. In one of the early episodes, at a campaign stop in Alabama, Tanner visits a prominent black preacher, an old friend from the sixties with whom he has fallen out of touch. He is hurt and shocked that his media director uses this connection as an impromptu press conference, gathering the entire media corps on site without Tanner’s knowledge. Tanner can’t believe his staffer would so blatantly step outside the mode of privacy, and for the next few episodes, Tanner freezes the staffer out of the major decisions.

Yet in contrast to these instances of moral uprightness is Tanner’s growing sheepishness over his daughter Alex’s youthful brashness. The series depicts the father and teenaged daughter as surprisingly close, but Alex’s conception of her father’s stance on certain issues seems to fall further left than Tanner would like to appear. In one sequence, Alex talks her dad into attending an anti-Apartheid rally just before he’s set to present at a Congressional hearing. In the flurry of the moment, under Alex’s pressure and in front of a bunch of reporters, Tanner not only attends the rally but also ends up handcuffed to a line of other protestors and then carted off to jail. While Tanner certainly doesn’t come across as in support of the racist South African government in his obvious reticence to act decisively, he seems supremely embarrassed to have been caught on camera in such a display. Alex seems to think that all one needs to do to be elected is to speak from one’s convictions, but Jack Tanner appears to know differently. Partially that wisdom must come from age, but I think it’s safe to assume that Tanner also accepts the inevitable tidying up of principles for manageable sound bites. In a Jimmy Stewart for President America, we wouldn’t see such compromises, but here in Altman and Trudeau’s universe, it’s at the forefront.

What stands out most prominently today about the depiction of Jack Tanner is how important it is to have elected officials who question themselves and our system. Tanner is an intellectual, engaged in the world around him, ideal when he feels he needs to be but pragmatic when the situation arises. Let’s just hope, as we come upon this November’s election, that kind of leader isn’t too much of an unfulfillable American fantasy as we so often see onscreen.